There’s no nuance in the gender equality debate – if we’re going to right the balance, that needs to change now

Gender equality is an issue that often dominates our dinner table conversations and the media we consume, yet somehow we still get it so wrong. Mostly because there is a tendency to view the privileges and inequalities between wealthy white men and women as representative of the disparities and inequalities facing men and women in wider society.

Last month, Bette Midler tweeted that “women are the n-word of the world”, a shockingly uninformed statement which makes no sense at all, but highlights what has come to be known as “white feminism” – an attempt to address gender inequality while ignoring the nuances of race.

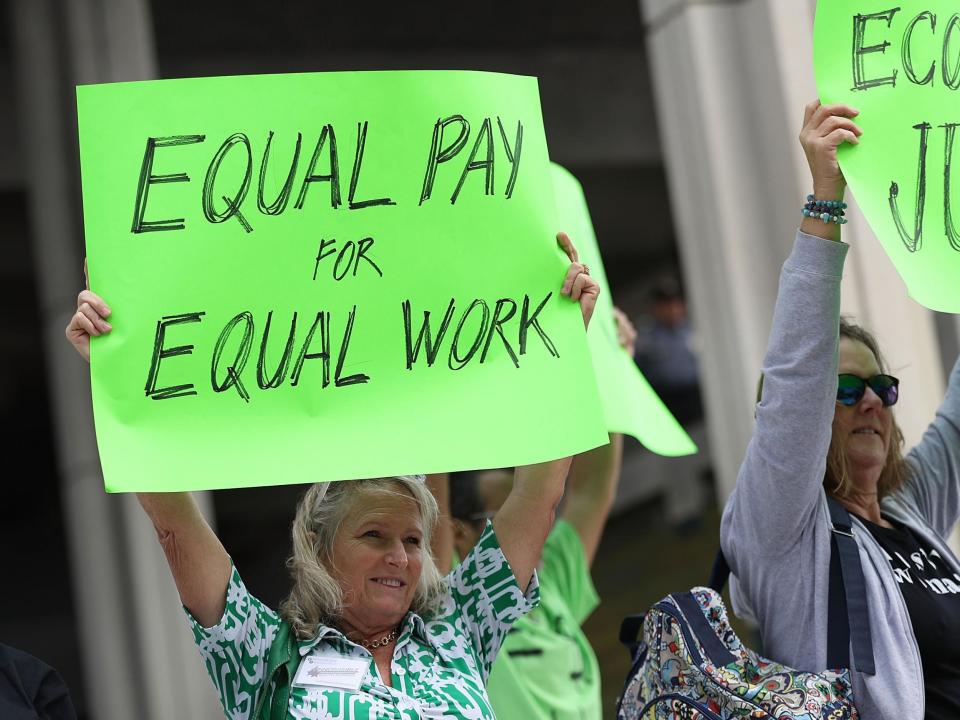

And last weekend marked Equal Pay Day, when women across the country set their out of office notifications to mark the 13.7 per cent gender pay gap – which effectively means women will be working “for free” until the end of the year.

While it is true that women share a great number of unique struggles across the board, the overwhelming focus on the gender pay gap seems somewhat disingenuous if it fails to also recognise how both race and class also impact working life and wages. As bell hooks once wrote: “Since men are not equals in white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal class structure, which men do women want to be equal to?”

The gender pay gap has been widely protested globally, and is one of the most prominent issues at the forefront of women’s rights movements. In the wake of #MeToo and the allegations of sexual misconduct against President Trump and Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, institutional bias against women across society has become an issue of public interest, and one that has united many women in their effort to seek justice in the workplace and beyond.

And yet there is a sense of bitter irony when the lived experience of black and brown women from working class backgrounds is merged with that of white women from middle class backgrounds in a sloppy attempt to tackle inequality; it simply does not reflect the facts.

Race is quite clearly a factor when it comes to structural bias, as seen in an ethnicity audit taken earlier this year which revealed that Bame public workers in London were found to be paid up to 37 per cent less than white public workers. Similarly, an investigation into Whitehall showed that ethnic minority civil servants were found to be earning up to a third less than their white counterparts, with seven departments (including 10 Downing Street and the cabinet) failing to share their pay gap data at all, which doesn’t inspire much confidence.

Understanding the pay gap through the criteria of gender alone is reductive, and homogenising the experiences of working women does nothing except further inequality. The gender pay gap for men and women across society at large may stand at 13.7 per cent, however the gender pay gap between white men and black African women stands at a much higher 19.6 per cent, with the largest pay gap being 26.2 per cent for Pakistani and Bangladeshi women.

Any attempt to close the pay gap must acknowledge these nuances. It is also crucial to understand these pay gaps within the wider context of structural disadvantage from the earliest stage – with nearly half of ethnic minority children living in poverty in the UK.

By the time they join the workforce, they are likely to experience employment discrimination, whereby those with African and Asian sounding names have to send twice as many applications as their white counterparts to get an interview, and can expect to be far less represented in leadership positions.

Just as employers have been put under pressure to take steps to tackle the gender pay gap, the same must be asked of them in regard to the race and class pay gaps.

While Sadiq Khan has vowed to tackle the “deeply entrenched” issue of race pay gaps – with greater transparency in salaries, anonymous application processes and diversity/inclusion training having been suggested as necessary measures to reduce race inequalities – the government must also ensure they are working to alleviate wider issues such as poverty and accessibility to higher education if they truly are committed to helping close the race pay gap.

When it comes to gender equality, leaving black and brown women out of the equation is no longer acceptable and empowering women should mean seeking justice for the most marginalised women.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News