No One Talks About This Free Breast Cancer Resource—But It Saved My Life

When Jessica Lavery Murphy, 36, of Broomfield, CO,was diagnosed with breast cancer almost two years ago, her head was swimming with questions: Should I remove one breast or both? What will my body look like? Should I freeze my eggs? She was handed a binder crammed with information on surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, "but I never opened it," she recalls. "I think I would have panicked. I wasn't qualified to make these medical decisions, and I needed someone to talk me through it - someone who was in my corner, who could connect me with the right resources, who could help me be my own best advocate." That someone, it turns out, was Nanna Bo Christensen, an oncology nurse at Boulder Community Health.

Christensen works as a breast cancer navigator; she's part of a rapidly growing field of patient advocates who function similarly to midwives, but instead of helping mothers-to-be deliver healthy babies, they steer patients through the confusing maze that is a breast cancer diagnosis. She would serve as Murphy's personal breast cancer navigator.

"Sometimes women are so overwhelmed, they didn't hear anything besides, 'You have breast cancer,' and they're frozen in that moment," says Christensen, who strives to get in touch with patients within 24 hours of their diagnosis. "I ask them what, exactly, they heard the doctor say, and help clarify any misunderstandings. Sometimes women learn [they have breast cancer] when they're on their cell phone in the grocery store, driving, or at work, and they are not in a place to ask any questions."

Some navigators, like Christensen, have clinical backgrounds and can answer those questions, then collaborate with patients and health care providers to craft a treatment plan. "We also coordinate appointments; a patient can quickly have four doctors she needs to see within a week, and that can be confusing," she says. "I coordinate it all, which relieves some of the stress. We keep the doctors connected, and we support patients emotionally." Other navigators may not have medical degrees but have undergone training to educate new patients on chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, and other treatment options; help with insurance woes; or even assist with meal delivery and transportation to appointments. (Non-clinical breast navigators are often survivors themselves.)

Softening the hardest blow

Murphy had sought medical attention in early 2015 for a breast infection; that kicked off a series of tests, including a mammogram, ultrasound, and the removal of a lump from her right breast, which wound up being cancerous. Her dual diagnosis was ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a common type of non-invasive breast cancer that originates inside the milk ducts, as well as invasive carcinoma. "Basically my entire right breast was filled with tumors," she says.

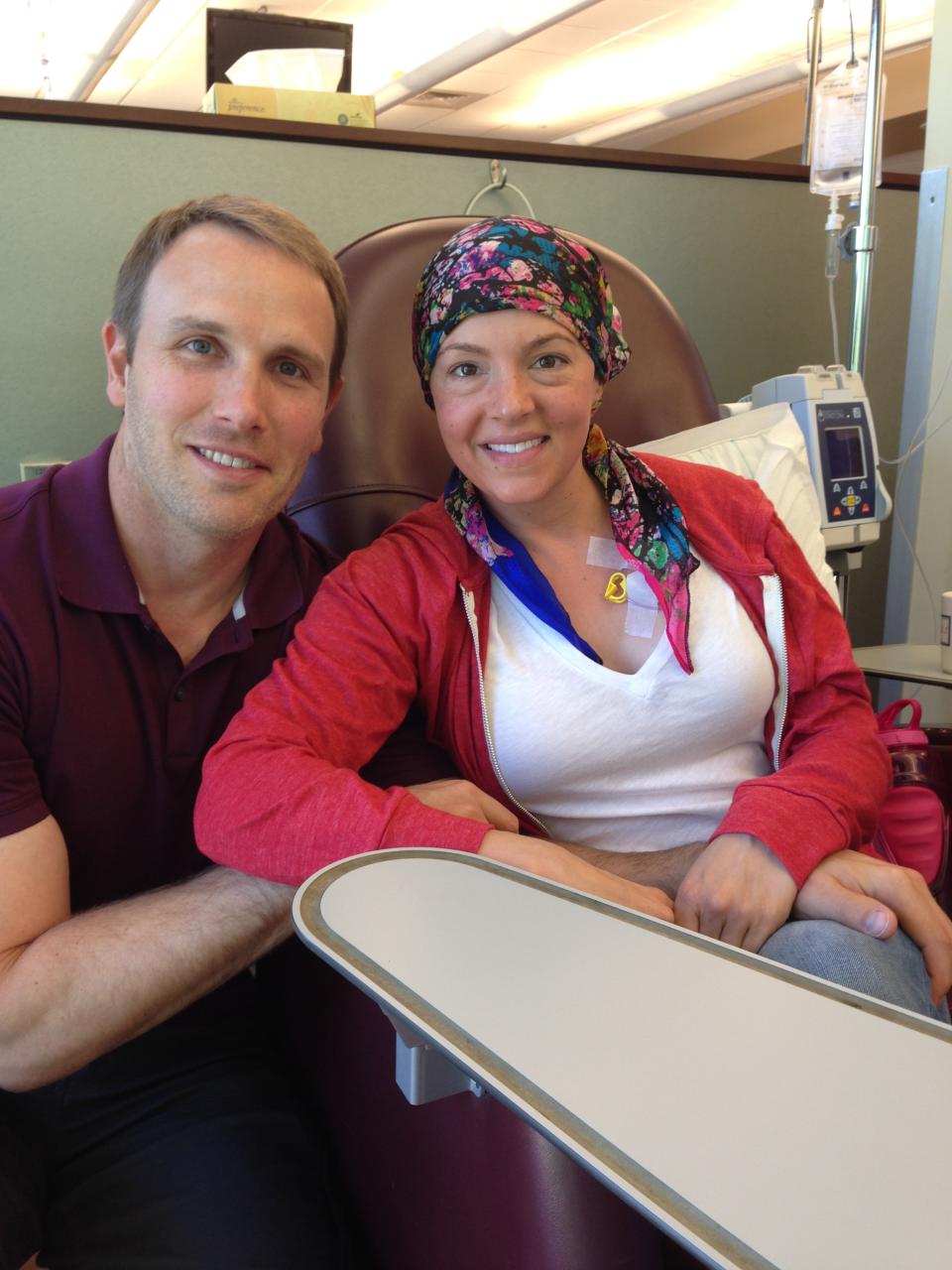

After that initial meeting with her breast surgeon, Murphy and her fiancé (now husband), Travis, met with Christensen. Murphy had never before heard of a breast cancer navigator, but she found herself instantly relieved to have a personal guide to lead her through these rocky, unchartered waters. One of the first decisions she faced was whether to have a single or double mastectomy. (There was no evidence of breast cancer in Murphy's left breast.)

While Christensen couldn't make that choice for her, she was able to point her towards reliable resources, connect her with breast cancer survivors, and acknowledge the difficulty of her decision. "She told me there's no one right answer, and encouraged me that whatever I decided would be the best choice for me," Murphy says. "She was full of information, plus she is a great listener, was empathetic and I felt like I could trust her." Having Nanna Bo, she jokes, "was kind of like spending time with the author of What to Expect When You're Expecting: Breast Cancer."

Progress in cancer care

The concept of patient navigation began in 1990 in Harlem, NY, when Harold P. Freeman, M.D., saw a critical window of opportunity existing after the moment of an abnormal finding but before diagnosis and treatment occurred. "President Nixon had declared the war on cancer in 1971, and we'd made relatively modest progress in reducing deaths, but by the '90s, we knew that progress wasn't being seen in certain racial and socioeconomic groups," explains Marc Hurlbert, Ph.D., chief mission officer for the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

"Dr. Freeman trained survivors and engaged them to reach out to community, encouraging others to get screened." The model has since evolved, Hurlbert describes, "from not just getting them in the door to get screened, but holding their hand through the whole process." By 2013, the American College of Surgeons had mandated that any cancer center seeking accreditation needed a navigation program by 2015.

"Patients with navigators have a higher quality of life, feel more empowered, and they feel like they have an advocate."

Before breast health navigators existed, "It was more up to the patient," says Hurlbert. "They've changed the landscape. Patients with navigators feel they have a higher quality of life, they feel more empowered to ask questions they thought were embarrassing, and they feel like they have an advocate."

A recent Journal of Clinical Oncology study showed that patients with a nurse navigator rated their care higher and reported fewer problems than patients without one. "Navigation saves patients' lives by helping to eliminate the nonmedical issues that prevent them from getting the life-saving care they need," says Monica Dean, program manager for hospital systems and patient navigation for the American Cancer Society.

Christensen has worked with women experiencing a recurrence of breast cancer-women who didn't have access to a navigator the first time around. The difference, they say, is tremendous. "It's the feeling of having a spokesperson versus 'being alone,'" Christensen describes. "From both a coordination and a psychosocial standpoint, to have one driver of all their services is endlessly positive."

Another pleasant surprise: Breast cancer navigation services are free ("Insurance companies recognize the return on investment," Dean explains). While no formal credentialing requirements exist, the American College of Surgeons' Commission on Cancer requires that all 1,500-plus of its hospitals, freestanding cancer centers, and cancer program networks provide patient navigation services; another 100 ACS-trained navigators are stationed in hospitals and treatment centers nationwide.

With the help of Christensen's guidance, Murphy ultimately decided to undergo a double mastectomy, followed by six rounds of chemotherapy, 36 days of radiation, and reconstructive surgery. Without her navigator, she wonders if she would have known how important it was to schedule her physical therapy appointments far in advance, before they fill up quickly. Without that preparation, would she have understood how painful it can be to raise your arms post-mastectomy, so much so that even brushing your teeth is challenging?

You're operating at less than 100 percent, so you need someone to talk through things with and bounce ideas off.

When Murphy began the fertility preservation process (freezing her eggs before surgery and radiation), only to be met with billing and insurance frustrations, the first person she called was Christensen. "She was my sounding board. You're in this emotional place, operating at less than 100 percent, so you really need someone to talk through things with and bounce ideas off. She's the one who said, "Look, everything's negotiable, you have leverage, you can push back [with insurance]. And she was right. Everything worked out."

In it for the long haul

With no evidence of cancer in her body, Murphy now needs to take hormone suppression medication for the next five to 10 years - "heavy duty drugs" that come with side effects like weight gain, bone loss, and hot flashes. She still stops by Christensen's office before or after appointments for advice and happily emailed her photos from her September wedding.

The navigator-patient relationship doesn't end once a patient's cancer is cured; survivorship carries its own side effects. "In general, common topics for women are depression, fear of recurrence, nutrition, sexuality, relationships, weight loss, exercise, pain, and figuring out their new normal," Christensen says. "Sometimes I offer a referral to the appropriate provider, or we simply just sit and talk."

Now approaching the two-year anniversary of her diagnosis, Murphy says having a navigator "was like having another mom. She allowed me to focus on getting better because someone else was handling all the other details. She gave me a leg up on the cancer experience."

Finding your navigator

The American Cancer Society has patient navigators nationwide. 1-800-227-2345

The American College of Surgeons' Commission on Cancer requires that all of its hospitals and programs nationwide provide patient navigation services. facs.org

The National Consortium of Breast Centers can direct you to a certified navigator near you

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News