No one can tell stories of inequality better than local news outlets

More than a year before Hurricane Harvey crashed into Houston, the Texas Tribune dug deep into how climate change and unchecked growth created a sprawling city vulnerable to devastation if the perfect storm hit.

In their investigation, the news site explained the factors behind Houston’s dangerously heightened exposure to hurricane disaster. In the days since Harvey flooded the city, ruined homes and businesses and killed at least 70 people in its path, the Texas Tribune’s work has been hailed as “oddly prescient”.

In fact, it was the natural outgrowth of great journalism by reporters who know their subjects and communities well and have covered these issues extensively.

One of the Tribune’s reporters, Kiah Collier, explained that she and her colleague Neena Satija, both reported at length on Houston’s the debate “over how, and whether, to build some kind of storm protection system to block the devastating storm surge that would accompany Houston’s ‘perfect storm’”. When Collier moved to the Tribune from the Houston Chronicle in 2015, Satija was already in talks with Pro Publica about the project and she jumped aboard.

“This previous coverage was definitely important; I had a grasp on the issue from the get-go and a bunch of sources,” Collier told me over email.

Collier says she and her team knew the story would be predictive, but not so soon. Rather than being spooked by the Tribune’s accuracy and ability to foresee what was coming to Houston, let’s consider instead the years of hard work, digging and trust building it took their reporters to get to that story. It wasn’t a magic trick; it was the result of truly persistent beat reporting.

In the face of massive cutbacks and tight budgets, this kind of reporting is happening all over America. I’ve been working this summer with the Guardian and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project on their new On the Ground project and I’ve been doing what might be the most fun part of the work. My job has been to create partnerships with local and regional news outlets like the Texas Tribune.

One of the goals of the project is to get these important stories about inequality in front of the people affected by them. We know that nobody does that better than local and regional press. Talking with dozens of editors, from Atlanta to Wyoming and Texas to Tulsa, has reaffirmed my belief that a massive share of the most important journalism done in America today is from reporters and editors committed to improving their own communities, not in amassing empty praise or followings on Twitter.

From beautiful new magazines to old-fashioned, small-town daily newspapers, local journalism is still fighting a tough financial battle, but doing incredible work.

In Atlanta, The Bitter Southerner has turned gorgeous reporting, writing and editing, wrapped under a killer brand name, into a battle against negative stereotypes about the American South. In Fargo, North Dakota, the alternative weekly newspaper High Plains Reader is investigating racism and violence in one of the only states in America without a hate crimes law. In Oklahoma, the online outlet Oklahoma Watch picks one or two topics each year that its top-notch staff can dig into at great length, with consequential reporting and insights.

These are just a few of the outlets I’ve had the pleasure of exploring this summer. All across America, I’ve spoken with journalists who are committed, working their butts off and forever looking for new ways to keep their organizations going financially. There’s no shortage of the will to do solid journalism, to help people better understand what’s happening in their towns and cities. But with the death of traditional newspaper funding and the ongoing corporate consolidation of American local press, the situation can seem grim.

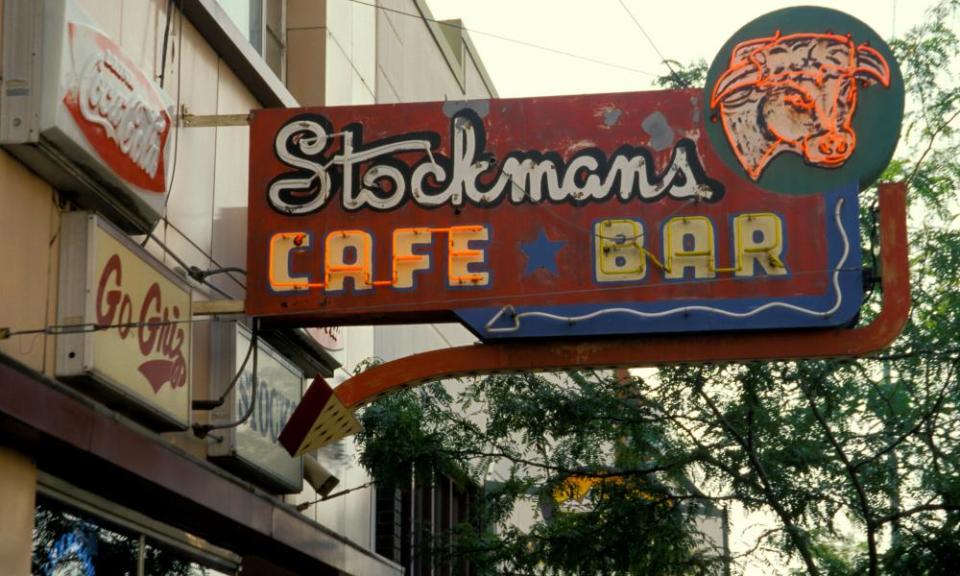

Even over the course of the summer, the media landscape in my home state of Montana changed yet again. (I wrote about Montana’s media and the dire state of local news in America earlier this year). Missoula’s only independent newspaper – the Missoula Independent – was bought by Lee Enterprises, the Iowa-based company that already owns four of the state’s largest daily papers and several smaller outlets.

The Independent was probably Montana’s lone remaining widely read critic of Lee’s cutbacks and coverage in the state and though its management has promised to keep it independent, the truth remains to be seen. Separately, the Lee chain scaled back yet again on its political coverage, moving one of its two remaining state reporters into a local education beat. The change went unreported in their pages.

Montana’s shrunken press is but one example of what happens to journalism when the ultimate motive is profit. In a report last fall, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that since 2004, more than a third of US newspapers had been sold at least once, and that the largest newspaper companies continue to buy up papers and squeeze out cash.

“Concerns about the role and ownership of newspapers have been voiced and debated since the founding of the country,” they wrote. “However, the dramatic shift in ownership of newspapers over the past decade – coupled with the rapidly deteriorating finances of community papers – brings added urgency to a new version of an age-old question: In the digital age, what is the civic responsibility of newspaper owners to their communities?”

Yet it’s wholly unclear whether non-profit models are better at serving the public good. A new report from New York University questions whether foundation-funded journalism is just creating more reporting for those who already have journalism – the wealthy (sorry, I can’t use the word “elite” as it’s almost always a misnomer), who live in clusters of America where media remains relatively strong.

So what can you do? The simple solution lies with you, dear reader. Find a news outlet valuable to your life and pay for it. Plain and simple. It’s not a long-term solution, but we need people to stop expecting the news be the same as air and sunlight – absolutely free.

On Sunday, we got some very sad news that a potential partner for On the Ground was going away, for an indefinite period. The editor of Indian Country Today – an invaluable source of news and information and the Native American diaspora in the United States – has gone on hiatus to figure out a new funding model. This month, the Guardian published a beautifully reported and written piece by one of their journalists on violence against Native women. Without her deep grounding in the issue, built through years of reporting, it’s hard to imagine how writer Mary Pember could have done the issue such justice.

ICT editor Chris Napolitano told me he thinks there are ways to get people to support journalism again, but we may be well beyond the era of subscriptions supporting reporting. What lies ahead, he suggests, is in adding value, going beyond the headlines and daily news.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News