No Stone Unturned and why Irish nationalism makes for better cinema than the loyalist cause

The new film from acclaimed documentary-maker Alex Gibney, No Stone Unturned, has been shocking audiences across the world since its release.

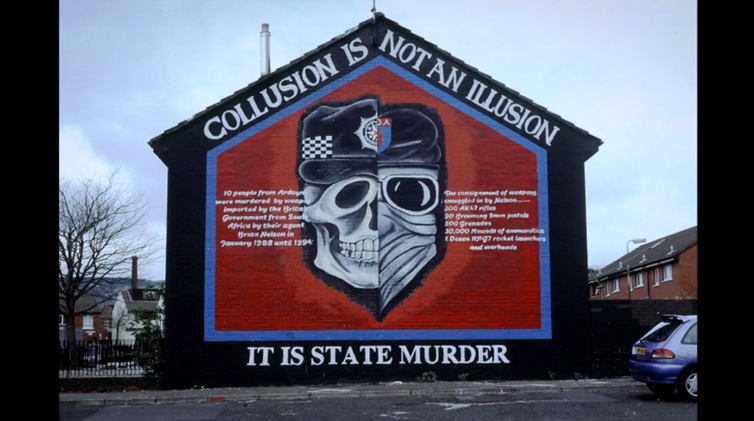

The documentary is an investigation into the 1994 loyalist paramilitary killing of six people in a pub as they watched the Republic of Ireland play in the World Cup. The film claims to prove collusion between loyalist paramilitaries and the British state in the undertaking and cover up of the killings and names the people responsible.

Gibney’s decision to investigate this incident over other historic crimes, such as those committed by republican paramilitaries, has added to the oft-repeated gripe from Northern Irish unionists that their community has either been ignored or maligned by filmmakers.

In response to the documentary, Ben Lowry writes in the pro-unionist newspaper, The News Letter saying: “There seems to be no-one out there in the film or documentary world who wants to depict the other side to this narrative.”

An examination of films which deal with Northern Ireland’s years of conflict suggest that there is truth in Lowry’s claim. Nationalist characters and themes are generally treated more favourably in film and appear much more frequently. So why is Irish nationalism seemingly attractive to filmmakers, and unionism not?

From Noraid with love

It is often suggested that the explanation for this cinematic deficit is because of Hollywood funding republican propaganda in the same way as Irish-America funded the IRA during the conflict. Films produced by Hollywood in the 1990s certainly add weight to this assumption.

But since 9/11 the idea of the idealistic freedom fighter committing acts of terrorism appears to have lost its appeal – there have been no Hollywood-financed movies about the Troubles since then.

This is not to say that examining sources of funding cannot still provide a possible explanation. Most of the films about Northern Ireland and the Troubles have received funding from the Republic of Ireland and mainland Britain. Very few films are funded solely from sources within Northern Ireland. This significantly undermines the autonomy Northern Irish unionism and loyalism have over representations of themselves.

Cry Freedom

A better explanation is that the unionist position is not as easy to articulate as the nationalist position – and not as well understood universally. Unionism’s desire to remain part of the United Kingdom has failed to pique people’s interest in the same way as the nationalist desire for a united Ireland.

In constructing a narrative, nationalists are able to draw on parallels with national liberation movements from elsewhere in the world. In contrast, the unionist narrative is much more unique – with the only parallels ever drawn being with the unseemly apartheid South Africa and the Ku Klux Klan. Needless to say, both these comparisons are rejected by unionists.

But the fact remains that loyalists seem unable to articulate their position with the same confidence as republicans. So the difficulty that outsiders face when trying to articulate the unionist perspective makes it difficult to represent properly in film. The same thing would also make it difficult for loyalists to attempt to make their own films to compensate for this cinematic deficit.

Attempts to articulate the unionist position also tends to result in the unionist narrative being perceived as a story defending a troubled status quo. These don’t make for traditionally attractive narratives. Certainly not when compared to the republican narratives of justifiable rebellion and the underdog fighting against injustice. This sort of thing is a staple of traditional storytelling.

Art is for Catholics

And the fact is that unionists are not known for engaging in the arts. As playwright, Gary Mitchell, who has remained close to his unionist roots and still lives in the loyalist Rathcoole estate in north Belfast told The Guardian back in 2000:

Protestants don’t write plays, you see. You must be a Catholic or a Catholic sympathiser, or a homosexual to do that. No one in our community does that because playwriting is a silly pretend thing.

Unionists traditionally worked in manual labour – either in the linen factories or in shipbuilding, whereas nationalists have been more likely to study the arts and humanities, work in theatre and – importantly – make films.

This imbalance shows no sign of abating. Stephen Burke’s film, Maze, about the 1983 mass breakout of 38 republican prisoners from the high security Maze prison went on general release in September 2017. Another in the pipeline, H-Block, to be directed by Jim Sheridan – director of the Oscar winning, In The Name Of The Father – was postponed due to problems in securing funding, but producers are confident they will start filming in spring 2018.

That’s not to say there have been no films about unionists – but if you have seen one or another of 4 Days in July, Nothing Personal, Resurrection Man or T2: Trainspotting you are unlikely to come away romanced by the loyalist cause. Other films such as Five Minutes of Heaven and ‘71 offer a more empathetic portrayal of loyalist characters. Ultimately, however, these films still show the loyalist cause to be flawed, unjust and lacking in the credibility often afforded to nationalism and republicanism.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Richard Gallagher receives funding from the Department for the Economy in Northern Ireland.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News