Norma Waterson was one of folk’s greatest voices – and greatest people

In the rain-sodden opening to the 1966 black and white BBC documentary, Travelling for a Living, a family of young folk singers are heading home to Hull. Big sister is driving the van, a cigarette pursed in her lips under her sharp, beatnik bob. She brooks absolutely no nonsense as she speaks about working-class culture being blitzed in the war, and how folk music can revive that community’s traditions. And then Norma Waterson sings, her full-blooded delivery coming straight from the gut, like torrenting water rushing over old stones.

Waterson, whose death was announced this morning, was one of folk’s greatest voices, and one of folk’s greatest people: proud, forthright and open about the music she made. I interviewed her in 2010 with daughter Eliza, in the family home in Robin Hood’s Bay, Yorkshire, shortly before she suffered an ankle injury that led to cellulitis and septicaemia and a four-month coma. After the illness, she had to learn to walk and talk again. She was brusque and funny but also incredibly tender, her granddaughter Florence at her knee, her musician niece Marry popping round for tea and biscuits, the room filled with laughter. This warmth was at the heart of her as well as her toughness, and it sang loudly in her songs.

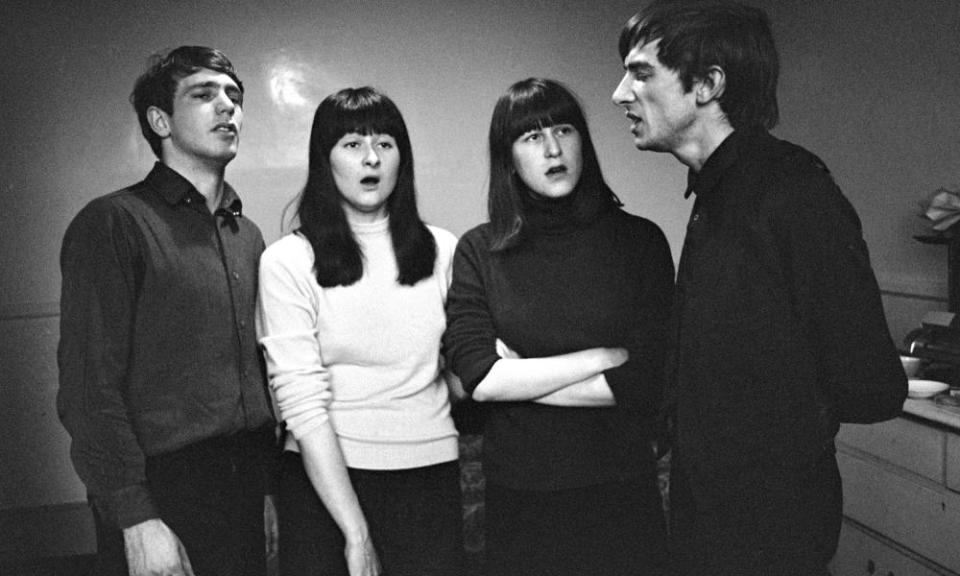

Norma’s family band, the Watersons, helped to spearhead the folk revival in the 1960s, playing London’s Royal Albert Hall and touring across the UK. She managed them, prioritising the values of real life above any professional commitments: one week of gigs were always followed by a week off so they could practise together, read books, and spend plenty of time with their children. Her younger sister Lal, brother Mike and she were its core, and they sang together as they had ever since they were children (they were brought up by their grandmother, from a Gypsy family, after their parents died young). Their voices had a bone-jolting beauty together: the title of their first album, Frost and Fire, conveyed their elemental power, as did the ballads they chose to sing on it.

Norma was also adventurous in her love of life and music. Following a man she loved to the Caribbean in 1968, she built up a huge calypso record collection there, and became a radio DJ for a few years. Her later records also boldly revealed her interests in music beyond British folk. Her 1996 self-titled solo album debut included songs by The Grateful Dead, Elvis Costello and modern blues and soul singer Ben Harper. Her last album with daughter Eliza Carthy, 2018’s Anchor, saw songs by Tom Waits, Nick Lowe and Eric Idle sitting alongside hardy traditionals.

Waterson’s solo album is how I first encountered her. I was a Britpop-era indie kid, watching the Mercury prize on TV, and I remember the lightning bolt of seeing a woman her age – 56 – looking like women I knew from ordinary life, full of charisma and character. She sang gutsily, without any semblance of prettiness or ego. She nearly won the prize, too. So close was the Mercury result that the jury debated for nearly four hours, but characteristically, Norma wasn’t aggrieved. “I wanted to adopt Jarvis,” she told me (Pulp’s Different Class was the eventual winner). “He wanted me to adopt him, too.”

The rest of her back catalogue holds numerous treasures, many of them with fascinating edges, rewarding appreciation from different perspectives. Her other two solo albums (1999’s The Very Thought of You and 2001’s Bright Shiny Morning) are more traditional but no less affecting: her take on Scottish ballad Barbara Allen is jolting in its simplicity, a cello and double bass echoing her depths. Her lead vocal on Red Wine and Promises, one of her contributions to sister Lal and brother Mike’s extraordinary 1972 album of folk-rock inspired originals, Bright Phoebus, is another high. Her rendition of a melancholy, drunken night out is accompanied by someone who was, back then, an old friend from the 1960s, Martin Carthy, on guitar: “the cheap red wine in me drunken brain / has left a burning flame in me belly,” she sings lustily. She and Carthy got together and married soon after.

The couple kept on keeping things in the family. With daughter, Eliza (named after Norma’s grandmother) they formed Blue Murder and the more traditional Waterson: Carthy; Norma’s rugged voice operated like a central nervous system in both. Her largely unaccompanied 1977 record with Lal, A True Hearted Girl, is also an overlooked beauty, the sisters’ voices clashing and curling together like whipping northern winds. Norma was devastated to lose Lal in 1998, only a week after her cancer diagnosis.

At the end of her life, ill-health beleaguered Norma, and the pandemic has been devastating for the family, bringing frightening financial pressures (Eliza recently set up a crowdfunder to help them through the recent winter). Throughout those last years, though, her family kept on bringing music into her life. In 2016, Eliza set up a festival, Normafest in Robin Hood’s Bay, to enable her mum to perform, and hired an old Methodist chapel in their home town to record Anchor live, renting Norma a house next door so she could “watch Corrie” and then come in to do her parts.

“She comes alive when she sings,” Eliza said. And so she still does on record and camera, her legacy a living thing, those waters torrenting on.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News