It’s not just Roe v Wade. Trump’s Supreme Court pick could challenge Brown v Board of Education

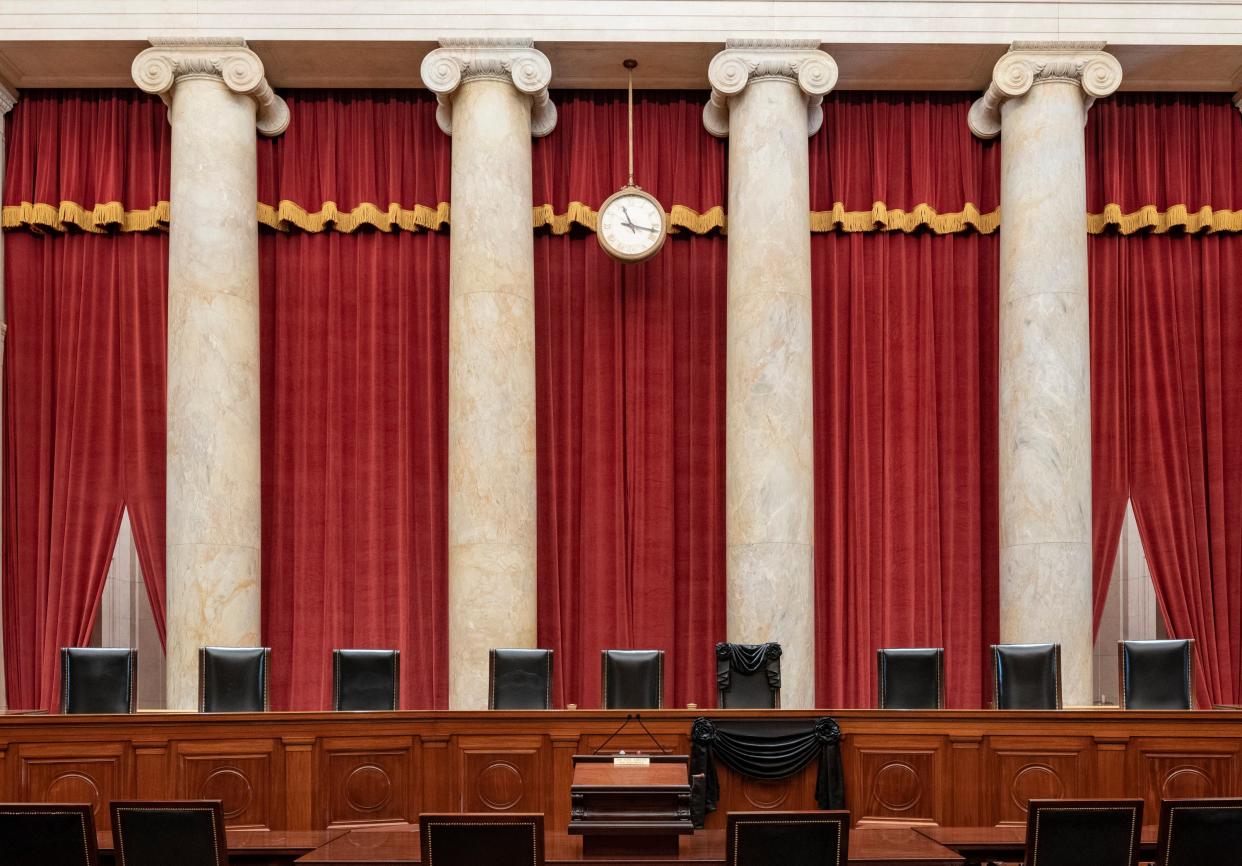

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death leaves an opening in the court’s four-strong liberal bloc, which could be filled by Donald Trump and the Republican Senate majority. Democrats and women’s rights advocates are once again sounding the alarm about the damage that could be wrought by a 6-3 conservative majority in the Supreme Court.

Partisanship and heated political rhetoric have accompanied nearly every Supreme Court confirmation since the Senate’s 1987 vote to reject Judge — and Watergate villain — Robert Bork, concealing what legal experts and political insiders say is a pattern of Trump nominees declining to support one of the highest court’s bedrock civil rights rulings.

The Supreme Court first affirmed a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy in the 1973 case Roe v. Wade. Ever since then, Republicans and their religious fundamentalist allies have made packing the judiciary with like-minded jurists a high priority. They have redoubled their efforts in the 18 years since George H W Bush appointee David Souter joined Justices Anthony Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor in upholding Roe’s “essential holding” in Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

However, many legal experts and Washington veterans fear that discussions about abortion could be obscuring Trump nominees’ hostility to another landmark civil rights case: Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

In the 1954 case, the court issued a unanimous opinion — authored by then-Chief Justice Earl Warren — declaring that “in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.”

In the years since, those nominated for the federal judiciary have frequently been asked their opinion of the Brown case. When the current Chief Justice John G Roberts testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee at his 2005 confirmation hearing, he responded to a question as to whether Warren’s opinion in Brown was the correct one with just two words: “I do.”

And during his contentious appearance before the committee in late 2018, then-Judge Brett Kavanaugh said the ruling — which is considered such an important milestone in American history that it is routinely taught to school children — represented “the single greatest moment in Supreme Court history.”

Yet despite the case’s status as a turning point towards equality in the canons of American constitutional jurisprudence, a significant number of nominees put forth by President Trump have refused to say whether they believe those nine justices who declared that Black children cannot be forced to attend separate schools from white children had come to the right decision.

As of last spring, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights found that nearly 30 Trump nominees for both trial and appellate-level courts had declined to state that Brown’s holding was the correct one, and frequently claimed that they did so because it would not be the place of a lower-court judge to evaluate a decision of the Supreme Court.

During a hearing to determine whether the Senate Judiciary Committee would vote in favor of Kenneth K Lee’s nomination to an open seat on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) — who has frequently put forth the question of Brown to nominees — expressed frustration with the trend.

“I am just at a loss to understand why no nominee is agreeing to answer the question and how every nominee is using almost exactly the same language to avoid answering it, and I think it is unfortunate because I think we ought to have free and open answers particularly on that kind of moral as well as legal question,” he said.

After now-Judge Wendy Vitter also refused to answer the question, Blumenthal offered his theory as to why this was so in a speech from the Senate floor: “The reason for giving such an answer is that Ms Vitter and the vast majority of President Trump's nominees do not really think that a lot of Supreme Court precedent is correct, and they would be perfectly happy for reversals.”

Vitter and most of the nominees in question have claimed their reticence on Brown simply follows the precedent set by the late Justice Ginsburg during her own 1993 hearing, when she declined to answer questions on matters that could come before the court.

But Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington Executive Director Noah Bookbinder, who from 2005 to 2013 served as Chief Counsel for Criminal Justice to the Senate Judiciary Committee, said none of the five Supreme Court nominees whose nominations he worked on—including those of Justices Roberts, Alito, Sotomayor, Kagan, plus the failed bid of Bush White House Counsel Harriet Miers—had any trouble affirming Brown.

“I think people can argue there are certainly cases that are going through the system about affirmative action-type programs and about considering race in admissions,” he said. “But that is far removed from whether you can have segregated schools, and…any nominee should…feel a legal and moral obligation to affirm that, as a constitutional principle, segregation is not permitted.”

Bookbinder went on to say, “I sort of understand the reason for caution, but I think it’s actually distressing that nominees apparently feel that even basic principles of equality and integration are in their minds up in the air enough that they don't want to opine on them.”

Another veteran observer of the judicial confirmation process, Harvard Law School Emeritus Professor Laurence Tribe, said the trend of judicial nominees refusing to endorse Brown is both unprecedented and troubling because of what it could signal about those jurists’ views on other significant constitutional questions.

“No federal court nominee, other than these Trump nominees, in the 66 years since 1954 of whom I’m aware — and certainly none who was confirmed — has declined to endorse that landmark ruling as correctly decided,” Tribe said. “That Trump nominees have routinely done so is simply jaw-dropping, and it’s a short step from that refusal to an insistence on being agnostic about whether the Bill of Rights binds the states by virtue of the 14th Amendment or whether the Equal Protection Clause applies to women.”

Michael Steele, the former GOP chairman and Maryland’s first African-American Lieutenant Governor, suggested in a phone interview that Trump nominees’ silence on Brown v. Board of Education leaves open the possibility that the President is deliberately nominating judges who are at least tacitly in favor of rolling back many civil rights protections.

“If you can't tell me that Brown v. Board of Education was decided correctly, that our public schools should, as institutions of learning, be desegregated, then you're telling me that the status quo prior to Brown was…the way to go,” he said.

For Bookbinder, Trump nominees’ refusal to affirm Brown raises the disturbing possibility that conservatives could begin a concerted effort to chip away at the case’s central holding in the same manner as they’ve done with Roe and Casey.

“I don't want to go so far as to say that I expect people to bring cases trying to challenge Brown, and I hope that we are not anywhere near that place,” he said. “But it does worry me as to whether it suggests an openness to litigation that gets closer to the kinds of principles that underlie Brown v Board of Education, even if not going right there.”

Steele, who is also an advisor to The Lincoln Project, also said the trend should set off alarm bells about the potential of a campaign to undermine Brown in the same manner conservatives used to mount successful assault on the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder.

“Given the Supreme Court decision on the Voting Rights Act, it does raise a flag that there may be some cases that pop up that would test the proposition of Brown,” he said, though he later added that he did not know what kind of case could be set up to do so.

Instead, Steele opined that the hostility to such a landmark civil rights ruling could spring from the mind of the President himself: “There’s no doubt that Trump lives in an idealized world of the 1950s that has become an infection [among Republicans]…which, by the way, is a bunch of crap,” he said. “But there seems to be this view that's out there that somehow, you know, that decision [Brown] disrupted the natural order of things, and they want to recorrect that. I don’t understand where it’s coming from, and we have to be alert as to how it may manifest itself in the court system and the judicial system.”

Stevens, whose book It Was All a Lie charges that the GOP has been infected with racism for decades, agreed.

“It's just all part of this effort to stop time, to go back to some mythical Shangri-La,” he said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News