Oh I do like to be beside the seaside, but many of our coastal towns need more love

My summer holiday of choice involves no passport, minimal cultural outings and as much time as possible spent immersed in 15C water. When I tell people that I am spending my break swimming in the North Sea off Yorkshire, reactions tend to run from “you’re brave” to “why would you do that?”. Which I imagine is similar to the comments I’d get if I announced I was taking a week to visit prisoners with whole-life orders. But I maintain that true pleasure requires not much more than an RNLI-supervised beach, a tide table and a novel to read between dips.

The British seaside is tragically underappreciated and disastrously underfunded. A lack of year-round jobs and lousy transport links are driving its residents away: four in 10 coastal towns are forecast to suffer a decline in their population of under-30s, with those in the north worst affected. Even the south-west, which attracts nearly half of the visitors to Britain’s coast, is struggling. Places that are a hive of cute tearooms and sun-dappled tourists in the summer pull down their shutters at the end of the season; the holidaymakers leave and a bleak and empty winter sets in.

From the late 19th century to the mid-20th, though, Britain’s coastal towns formed a halo of small paradises around the edge of the island, initially driven by the craze for spa towns. This history is visible in once magnificent, now often derelict, architecture, such as the painfully neglected Birnbeck pier at Weston-super-Mare. In Scarborough, the Grand Hotel overlooks the South Bay in Victorian splendour; formerly a refuge for the wealthiest tourists, it was dogged by food poisoning scares in the 2000s and you can now stay for less than it costs to put up in the nearby Travelodge.

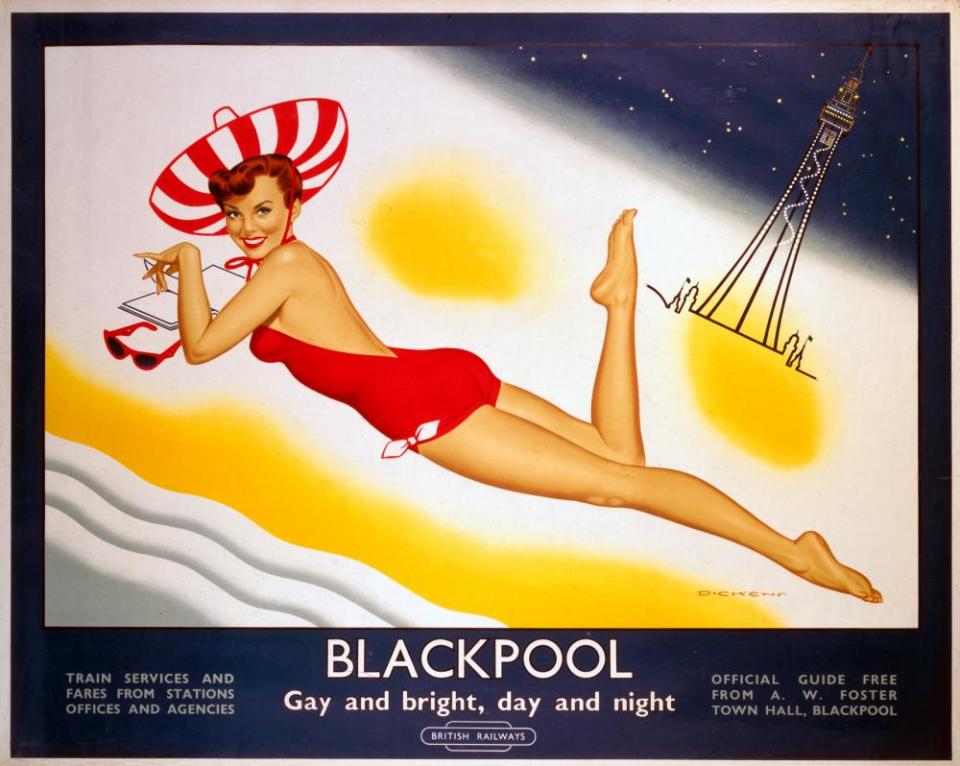

Railway ads from the 1920s and 30s show the leisure and luxury that a trip to the seaside promised. Come to Blackpool and find a glamorous redhead reading on the yellow sand, back enticingly bare in a halterneck costume, the illuminations of the tower glinting overhead. Filey in North Yorkshire is painted as an art deco paradise, enjoyed by a beatific trio of mother, father and toddler in elegant bathing suits. (There’s a less salubrious seaside than the train companies chose to show, as well: fresh air in your lungs, money in your pocket and strangers on the esplanade could give a person ideas.)

But in the 1950s, postwar prosperity combined with the growth of civil aviation to suck tourism away from Britain’s coast and now place names such as Skegness and Minehead have a distinctly bathetic sound. My childhood didn’t involve many trips to the seaside and those I remember didn’t involve going in the sea much. In Robin Hood’s Bay in Yorkshire, I bothered the inhabitants of rock pools, but I never went deeper than my shins. This was understandable, given that in the 1980s a lot of Britain’s beaches were disgusting and my parents probably didn’t care to turn their toddlers loose in a soup of litter and sewage.

No need for such caution now. Since EU legislation on water pollution forced the clean-up of Britain’s coast, 99% of Britain’s designated beaches are safe for swimming. It’s a depressing Brexit irony that, as it makes the continent more expensive and less accessible, it could also become an excuse for cutting the red tape that has made domestic tourism possible without a dose of E coli. But this is, admittedly, not the most depressing thing about Brexit and in any case Britain’s seaside deserves to be seen as more than a cheap alternative to going abroad.

It also deserves to be more than a period piece, although part of the seaside’s joy is definitely nostalgia. Sitting at a chrome and Formica table in Scarborough’s Harbour Bar, ordering ice-cream sundaes with names such as peach Melba and pear Valentino (after Dame Nellie and, presumably, Rudolph) will put a person in a pleasantly old-fashioned state of mind. And when you are cold all the way through your internal organs from 10 minutes in the waves, it’s a scalding builder’s tea you want and not a flat white.

The reason we should be investing in, and protecting, the beauties of Britain’s seaside isn’t so we can live in an imaginary version of the past, though. The number of saltwater lidos and wrought-iron piers lost to vandalism and council indolence is sickening: we should be saving those things so we can go on using them. The gorgeous art deco Jubilee Pool in Penzance underwent seemingly catastrophic damage in 2014, but was rescued by the community and shows how even the most dilapidated bits of our coastal heritage can be revived.

Part of the reason that seaside structures are so vulnerable to carelessness is, of course, that the sea is a wild place: maintaining anything is a constant battle against lashing winds and erosion. (Maybe the proximity to wildness is what made coastal resorts such as Brighton destinations for sexual freedom.) One of the thrills of going back to the same cliffs again and again is seeing the rocks reshape with each visit. The impossibility of developing fragile coastal land is a salvation for wildlife – a few steps from the road, you’ll find the air busy with insect life, and swallows feasting on the wing.

I’m keeping my favourite beach to myself – I’m not sure I want to share it with golden-age numbers of tourists – but there’s plenty of room on Britain’s coast for more visitors. Take yourself to the seaside, dive all the way in, fill up on chips and ice cream and don’t forget about the coast when summer is over.

• Sarah Ditum is a writer on politics and culture

Yahoo News

Yahoo News