These online maps are tracking the outbreak of violence and harassment in America

It has only been three weeks since Donald Trump won the election, but in that time, harassment and hate-related incidents across the country have increased. To fight the outbreak of violence and intimidation, some organizations are turning to digital maps.

The wave of horrible acts prompted even Trump himself — when pressed by 60 Minutes reporter Leslie Stahl — to tell supporters allegedly perpetrating the crimes, "Don't do it, it's terrible." He added, "Stop it."

In a report published on Tuesday, the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights organization based in Alabama that has been tracking hate groups for 45 years, published an article that looked at the spike in hateful harassment and intimidation incidents across the U.S. in the first 10 days following the election, reporting nearly 900 in all.

In the ten days following Donald Trump’s victory (Nov 9-19), we’ve confirmed 867 incidents of harassment, intimidation and even violence pic.twitter.com/4KXG6LNCzi

— SPLC (@splcenter) November 29, 2016

This increase has spread fear among many communities, particularly the Muslim community, a frequent target of aggression by Trump's campaign. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo even recently announced a new police unit in New York to fight the rash of hate crimes in that state.

Several organizations are tracking these incidents and sorting the data in an effort to help call attention to the attacks and hopefully put an end to them.

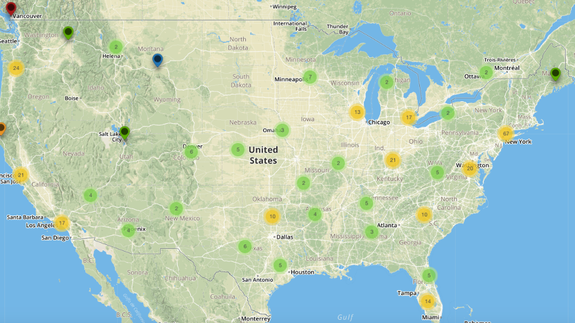

Ushahidi, a non-partisan, Africa-based company that creates open-source mapping products, has launched an online map that displays incidents of violence, hate speech, harassment, and protests in the United States since the election.

Ushahidi's map tracks incidents reported by Twitter, email, SMS, and web submissions. Users can also sign up for alerts of incidents reported nearby. Once submitted, the incidents are vetted by a group of volunteers which, according to the company, include journalist Shaun King, professors at MIT and Harvard, and Crisis Mappers. (So far, 133 incidents posted have been verified).

Users can filter incidents on the map by category and can also view the incidents in a list format.

Currently, the mapped incidents run from Nov. 1 through Nov. 22, 2016.

Another similar map, the Harass Map, reports similar incidents and uses similar vetting, but links to reports of the incidents published in the media.

Patrick Meier, co-founder of CrisisMappers, which created the map, told Mashable that the map focuses more on specific groups being harassed rather than a specific type of harassment.

According to Meier, "What we wanted to do was collect, curate existing reports already published online whether it was mainstream media or social media and be sure that we cited the original sources so that anybody could go back and follow our process as well."

This, says Meier, helps the volunteers who corroborate the reports factcheck and find any potential errors. And users can also submit errors they discover on the map via the site's submission form.

As for those sources themselves, Meier says the group makes sure to link reports from what they deem credible outlets and, for social media reports, they "find corroborating evidence from one or two mainstream media sources" to confirm the reported incidents.

Help us collect & map public reports of harassment & attacks against US minorities: HarassMap.us (Partners: Harvard, MIT, UCLA, ESRI pic.twitter.com/15ulk9Nyrz

— CrisisMappers (@CrisisMappers) November 17, 2016

Meier, who previously worked on similar maps involving the 2008 Kenyan elections and 2010 Egypt elections for Ushahidi, shares the data with that company and coordinated with other outlets, including ProPublica, "to make sure we were all working toward the same goal."

The Harass Map, though, adds a positive twist: reports of others helping victims of harassment, like the motorcycle club who rallied to the aid of a boy harassed because of his skin color.

Meier spoke of his background working on conflict early warning systems in Africa — which spurred the creation CrisisMapping — and the importance to reflect instances of peace, of cooperation and collaboration, alongside warnings of conflict.

"It's important to surface that," he said. In regards to the Harass Map, Meier added it was important to "show both narratives, that we show the good that's coming out, that people are helping others. It's not all bad."

It also, he said, helped clear any distortion that could come from media coverage.

So as tools like these bring more attention to incidents across the country, there's also hope they can bring more attention to ways to help as well.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News