When All of This Is Over: On the Narrative of Protest and Progress

I keep refreshing my social media feed looking for the end of the story.

One of the promises of the internet is that if you keep clicking, you'll see everything. And though I know, we all know, that's a lie, there are enough small tidbits of closure to keep us scrolling, clicking, reacting, and scrolling again. The celebrity scandal that bubbles up into a dramatic arc, climaxing with a public apology, for instance, has a neat enough structure that it feels satisfying, like a movie. Or, in our personal lives, through social media we watch friends and strangers grow up, lose and find love, experience triumph and grief, all with the expediency of a montage.

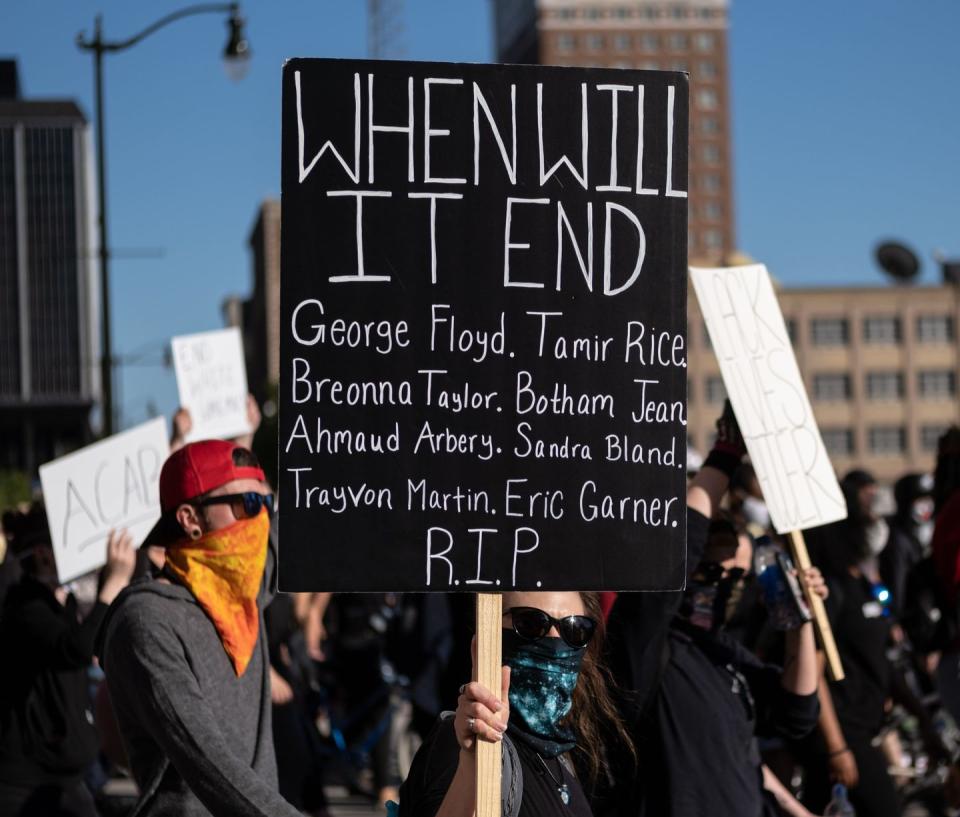

The implicit narrative of what we see posted online extends, too, to viral videos of injustice and state-sanctioned violence. We view the footage, we express our outrage, perhaps someone online uses the resources of the internet to identify those involved, ideally we listen to organizers and activists and follow their direction. And eventually, we assume, our social media feeds will reward us with a conclusion. And what is the conclusion we seek? A resignation, a conviction, an apology, an election. Though we know that, for instance, nothing online or in reality, will restore the lives of Breonna Taylor or George Floyd, there is the embedded hope that something will change. And, as in a movie, the screen will fade to black, the story over.

And, at least from a narrative standpoint, I like to imagine that the desire to fast forward to the conclusion, to hasten the reckoning, is part of what fueled the proliferation of actual black screens on #BlackoutTuesday. Like other social media campaigns designed to show solidarity, #BlackoutTuesday seems to be a discrete task meant to signify larger systemic change. By posting a black square on social media, Instagram particularly, many users are expressing a desire to mute themselves and perhaps amplify Black voices. In the best lights, it has some of the tools of the "step up, step back" strategy often employed by community organizers. In my scrolling, I've seen it paired with sentiments like "Enough is enough" or "the time is now." If it's not a conclusion, it seems, the black square wants to represent a turning point.

The question, then, is are we actually at a turning point?

For months now we have been scouring CDC data in search of signs of another turning point. To stanch the spread of coronavirus, we were told, we'd have to flatten the curve and once the curve was flattened, we could begin to return to parts of our lives, piece-by-piece. In this light, the fight against the destructive effects of the pandemic is a little anti-climactic. There is no grand resolution, but rather a gradual reinstatement of normal life. But, crucially, normal life would be reinstated. "When all this is over..." we vow, pencilling in plans for a date that's yet to be determined but is nevertheless fixed in our minds. I say it all the time, "When all this is over...," though I find it hard to define how big "this" is and what "over" really looks like.

Some decided that they'd had enough, that the story had run its course and they wanted their conclusion now. They flouted rules or engaged in aggressive protests that, somehow, did not produce shows of force by police. Some have returned to their offices or their favorite restaurants or to vacation plans made ages ago. And though life clearly has not returned to normal, I imagine there must be some sense of closure for them.

There is an obvious dissonance between the responses to armed groups protesting quarantine a month ago and the responses to protests against police brutality this week. But there's a strange narrative synergy as well. The former group was using the tools that are readily at their disposal to demand a return to what they considered normalcy. And the latter group is experiencing the brutal but logical extension of that normalcy. This disparity, coupled with a social media feed that shows some people fully engaged in their old lives again, prompts the question of whether we are, or were ever, in the same story at all. And, if we're not in the same story, how do we coexist?

Aesthetically, the utter bleakness of a social media feed filled with black squares in the place where life and color used to be is as jarring as a feed filled with people returning to normal. But the initiative now known as #BlackoutTuesday started off with a much different vision. Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang, two black women who work in the music industry, proposed June 2 as a day to use the hashtag #TheShowMustBePaused to, in their words, “take a beat for an honest, reflective and productive conversation about what actions we need to collectively take to support the Black community.” Focusing on the music industry's often predatory relationship with Black artists and Black work, the intention was to put pressure on industry leaders to be accountable for their actions. On The Show Must Be Paused's website, Thomas and Agyemang posted resources for supporting protests and further education. They wrote, "This is not a 24-hour initiative. We are and will be in this for the long haul."

#theshowmustbepaused | For more information on how to take action visit theshowmustbepaused.com

A post shared by @ theshowmustbepaused on Jun 2, 2020 at 8:42am PDT

As celebrities and music companies began posting about #TheShowMustBePaused, the second, unrelated hashtag #BlackoutTuesday popped up, and with it, different guidelines.

A post shared by Columbia Records (@columbiarecords) on May 31, 2020 at 11:40am PDT

Literally overnight, the Show Must Be Paused's music-focused, long haul initiative was transformed into a widespread but finite campaign. And while it's clear that those posting with the hashtag see it not as a solution but a step, what happens if the distance between here and the end, whatever that may be, is a lot longer than expected? The instant gratification of social media and some of the popular narratives around the history of activism have compressed the perceived time between action and result. But the truth of this story, the story of the nation, is that the path to the end is long and uncomfortable.

On Tuesday, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, in a rebuke of President Trump, quoted the words of Presidents George H. W. Bush and Obama from other instances of public outcry against police brutality. Though the words were meant to be an example of a job done right, they also prompt the question of how much of a turning point this can be if words from 30 years ago still apply.

NEW: Speaker Nancy Pelosi says a president of the United States “has the responsibility to heal,” quoting former President. George H. W. Bush following the Rodney King riots and Former President Barack Obama’s following the killing of Eric Garner. https://t.co/cVIWqSfzSR pic.twitter.com/GlM4TXitYC

— This Week (@ThisWeekABC) June 2, 2020

I wonder if part of the problem with reaching, or even visualizing, an end is that over and over we're told that we've reached the happy conclusion when really we're being held in place. Take the Los Angeles Insurrection that followed Rodney King's beating at the hands of the police. It took place in South-Central, including Watts, a neighborhood that was also decimated by an uprising in 1968, after Marcus Frye and his mother Rena Frye had an altercation with police. After the Watts uprising, the city formed a commission to investigate the causes of the uprising and to suggest solutions. The 110-page McCone Commission report highlighted decades of institutional racism and subjugation of the Black residents of Watts, resulting in a population already decimated by poverty and racially-motivated police brutality before the uprising began. Among other initiatives, the Commission recommended educational programs, improved police-community ties, increased housing, job-training projects. However, in 1990, 25 years after the uprising in Watts, members of the Commission expressed dismay to the Los Angeles Times that most of their recommendations had not been enacted and prospects for the residents of Watts remained largely as dire. Two years later, the insurrection after the King verdict would again plunge the area into turmoil, prompting George H. W. Bush's speech, which would, 28 years after that, be quoted by Speaker Pelosi during another insurrection.

There is an idea popular in the predominant narrative of the United States—which is to say the narrative almost entirely constructed by the white imagination—that we have moved beyond the struggles of the past. This is particularly true around issues of race, where the work of activists like Martin Luther King, Jr., Angela Davis, and Marsha P. Johnson, and legislation like the Civil Rights Act are defined as plot points hurtling us to a triumphant climax. But the lived experience of many people in this country, across many generations, reflects a different reality. In this reality, the work of those activists and hundreds like them have produced clear positive results but the larger structure of white supremacy and structural oppression remains intact. We can't claim to be in the same story if we aren't heading toward the same end. When we say, "When all of this is over," do we mean the end of a white supremacist society? And if so, how much are we willing to do to get there? How much of the story that we're in are we willing to divest from? And how long are we willing to work for it? The end can't be a return to normal. Normal is where we are.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News