In their own words, how Americans are experiencing the climate crisis across the US

It has been a year of climate disasters in the US that blindsided even the most seasoned scientists.

From hurricanes and severe heatwaves to droughts and flash floods, the climate crisis is unfolding in a myriad of expected and unexpected ways in the lives of regular Americans.

Below, in their own words, Americans of different ages, professions and backgrounds, from different states, share how the impacts of a heating planet are changing their daily lives.

The interviews below have been edited for length and clarity.

Bruce Fernald, 70, lobsterman, Maine

“I live about three miles off the Maine coast on Cranberry Island. It’s a mile and a half long , a mile wide. About 70 people live there year round. We’ve been lobster fishing for six generations and I’ve been at it for 48 years. I have two brothers that go fishing and my father was a fisherman for 50 years. He’s no longer with us but he set the stage.

I go lobstering from about 1st April until December. I fish 800 traps, which is the state limit, and don’t go more than three miles offshore. I get up at 5am and get back between 1.30-4pm, hauling 250-300 traps a day with one crew member on the boat. The rest of the year I work in my shop building new traps, painting my lobster buoys.

We formed a co-op about 46 years ago. It’s 25 fishermen with a manager to run the dock. We bring our lobsters in every day, weigh them, and when we have a boat-load or two, they’re taken to the mainland to two dealers and then to Portland. They go all over the world from there.

The changes to the ocean have been major. When I started fishing, the lobster catch for the whole state of Maine was 20 million pounds [a year]. Around 15 years ago that really took a jump and now we’ve been up as high as 130 million pounds.

The number of lobsters has exploded. More than likely it’s due to warming water and the lack of conservation measures in other fisheries like cod fish, one of the main predators of lobsters.

We’ve never seen so many lobsters, and it’s the same up in Canada. They’re having banner times.

About 15 years ago I went up to Prince Edward Island in Canada to go fishing with a guy for the day. A few of the lobsters were tiny but had eggs, I had never seen that. But in the last 10 years that’s what we’re seeing in Maine. We assume it’s because the water is warming and the lobsters are maturing earlier. It’s mind-blowing to see so many little lobsters here.

Other things that I’ve noticed is that starfish, which disappeared for years, have come back. Sea urchins have disappeared but they were fished on pretty heavily back in the Nineties and had a disease that wiped them out. They were a major nuisance to lobster fishermen, you’d get spines in your hands and they’d chew the twine of the traps. Now they’re gone and we don’t miss them a bit.

I think Massachusetts is holding its own but around the Cape [Cod] and down towards Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York, that fishery has practically died. There are still offshore fisheries but inshore, the pollution and warm water just drove the lobsters away. Back in the Seventies, Eighties, Nineties they were doing big time. And now it’s collapsed. Hopefully that won’t happen here.

The younger guys [in Maine], I’m sure they’re concerned about it because they’ve got half million to million-dollar boats. They’ve never seen bad fishing. Always good times.”

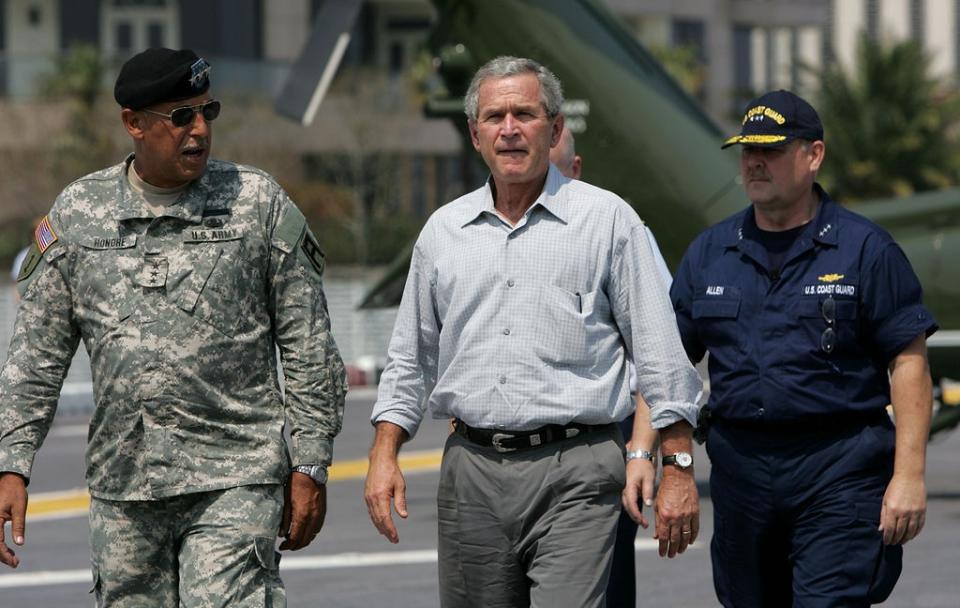

Retired US Army General and disaster preparedness expert Russel Honoré, 74, Louisiana

“Climate change is having a direct impact on Louisiana. Throughout our Gulf Coast in the last two years we’ve had five hurricanes make landfall. Laura and Ida were record-breaking storms in terms of intensity, and the damage they created in south Louisiana.

Much of it is permanent. Our coastline is disappearing: we lose a football field of dirt every hour. It’s being measured by the hour, not the year and as we lose land, we lose access. We’re already moving people inland like the Pontchartrain and Isle de Jean Charles tribes who have had their land overtaken by water. Since the first COP [the annual UN climate summit], there has been three-and-a-half inches of sea level rise. That’s real to us in Louisiana.

In New Orleans, we put in a $14billion levee system after [Hurricane] Katrina. [During Ida] the city didn’t flood so we know investment and protection works. But the 180mph wind took the entire power grid out. It’s not designed to deal with climate change.

It was similar to what happened in [Hurricane] Maria in Puerto Rico. That’s two experiences where the grid does not stand up to hurricanes.

Much of our technology is last century when we did not have the climate impacts we have now.

When the grid went out, it took out the internet so first responders couldn’t communicate. The storm also closed many gas stations so medical workers couldn’t get to work. The other lesson is that you can’t depend on one generator. When you’re running a hospital, you need a backup to the backup.

And all this happened during the time of Covid. The hospitals in south Louisiana that would normally evacuate in a hurricane had no place to go, so they had to shelter-in-place.

It’s a horrible situation but we worked through it, people helping people. But a lot of people died as a result of the living conditions post-storm.

Most credible scientists associate [climate change] with manmade activities. And boy, do we create a lot of manmade activities in Louisiana. We have 150 chemical plants between Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

If Louisiana was a country, we’d be the third-largest liquefied natural gas producer [LNG] in the world. LNG creates a lot of methane - one of the worst of the greenhouse gases - so the amount we’re putting into the air is significant.

We could cut methane within six months if the federal government told [companies] to do it but we’re giving them until 2030. That’s bulls***.

They want to use federal funding to cap wells that [oil companies] drilled. They call them orphan wells — they are not orphan, we know who drilled those wells. They are just abandoned.

But they need to be capped and at the end of the day, we live with the sins of our fathers who created these dumb-ass rules and gave so many subsidies to oil and gas.

The [oil and gas] industry has polluted the knowledge base of America to believe that they’re the only source of energy. They played on that misinformation to the detriment of our environment.

And every time we raise hell with them about pollution they raise the price of gas, which is what they are doing right now.”

Holly Bradley, 32, farmer and climate organizer, West Virginia

“My husband and I are farmers and caretakers at the Gesundheit Institute, Dr Patch Adams’ free hospital clinic where we host workshops around alternative healing and community. We also have our own eight-acre farm, focusing on regenerative and organic agriculture.

We met at West Virginia University where I studied design with a minor in horticulture. So I went to school for growing plants, really. When we graduated, we lived in California for about nine months on a farm. But we really missed West Virginia and decided to come back.

I’m originally from the small city of St Albans. My dad worked at a chemical plant there for 40 years. He was in the control room as an operator but was also an EMT and a firefighter so anytime there was an explosion, he was one of the first on the scene.

He retired early with rheumatoid arthritis. My dad would always have suffered with [the condition] but I think his job expedited it. When he was in his forties if he didn’t get his medicine, he would be crawling around the house. My mom works at the West Virginia Lottery for the health insurance for my dad. He’s 67 now and has to take very expensive medicine to be able to walk.

Both my mom and dad’s families are from West Virginia. On my dad’s side we go back nine generations. I have older, twin brothers, Aaron and Lorne, who went into the Marine Corps after high school.

They served four years and on getting out, Aaron went to West Virginia University for a wood science degree. When he graduated, he had a hard time finding a job and one of his buddies from the Marines got him a job on a horizontal drilling [fracking] rig in Pennsylvania. Lorne is a boilermaker at a coal-fired power plant.

We live in Hillsboro which is very rural and has a population of 264 people. The area is called “Little Levels” - it’s this lovely flat area where you can look onto the mountains, which is rare in West Virginia.

The closest grocery store is 30 miles away, but those are “mountain miles” so it takes about an hour to get there. Hillsboro has two gas stations, an elementary school and a public library but no other services. A couple years ago, our friend opened a store which sells more organic choices, which now has a cafe too.

Most days I work from the library because my internet at home isn’t good enough for Zoom calls. Sometimes I can barely open up my email. Pocahontas County is the size of Delaware and the whole county has a lack of internet access. That doesn’t sound important to people who don’t have to worry about it but it was a big challenge especially in Covid when people are working remotely.

When I was young, snow storms were a regular part of winter in West Virginia. Pocahontas County used to get called “Little Antarctica”.

In 2014 my husband worked at Snowshoe Mountain Resort. I remember getting snowed in for a week. It’s not like that at all now, the seasons have been cut shorter and shorter. It’s like summer until October and in winter it’s rare to have coldness like there used to be. Snowshoe has invested in other activities like mountain biking.

A scary issue to me from climate change is the increase in tick population. It’s not getting cold enough to kill the ticks outright. About ten of my friends, and my husband, have Lyme disease. I think we’re all going to end up with it because we live so close to nature.

Chemical bug repellent isn’t good either so we wear rose geranium essential oil outside and check our kids for ticks like five times a day. Monongahela National Forest takes up half of Pocahontas County so there’s no escaping the ticks. Other tick-borne illnesses, like Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, are popping up in West Virginia when that used to only be in Colorado.

Farming is very unpredictable, and already this painstakingly hard thing to make money at. Climate change is just snowballing the challenges.

In May or June 2015, it rained nonstop for six weeks. Everywhere was mud and no one could plow any fields, so people planted much later than they should have. Fast forward to the next summer and we had a “1,000-year flood”. All 55 counties in West Virginia were affected. Some friends lost entire crops.

[At the time] there was a viral video of a house floating down the river on fire, which kind of summed it up. FEMA (the federal disaster assistance agency) was here but today if you drive through parts of West Virginia, a lot of houses have fallen in on themselves. People don’t have the money to clean up that kind of stuff.

These issues compound on each other - all of that debris gets into the rivers. And when we have flash floods, for example, coal slurry ponds leach into the groundwater.

In June 2019 we had a hail storm like nothing I have ever seen before. I was in the car with my three-year-old at the time and golf ball-sized hail came down, leaving dents all over our house and completely annihilated vegetable crops.

You need some sort of dependability with seasons. And you can take all the precautions you like but without support in terms of investment and infrastructure improvements, it’s very hard for people to do it alone.

When we talk about climate change in West Virginia, it’s about jobs. How are we going to get jobs that pay as well as the coal mines or the frack wells? In my county, the majority of the people live below the poverty line. If the coal mine shuts down everybody is affected.

In West Virginia, we’re proud of the coal mining history and culture because that’s how people supported their families. It’s not about canceling that history or that story but regenerating it with something new.

Like with my brothers — there’s not like tension between us because I’m a climate advocate and they work in fossil fuel industries. They have to support their families and are doing their best. If there’s not opportunities to do something else, we can’t be mad at them.

Why not put solar or wind farms on the mountaintop [coal] removal sites where nothing will grow and it’s flat, open land? Then put people in these coal communities to work there. Make sure people are taken care of, are not left behind, and get buy-in from coal communities.

West Virginia’s always seen as the problem child who everyone blames when progressive [legislation] gets blocked. But polling shows more than half of West Virginians support a clean electricity grid. You don’t hear about that. They just want to talk about how we’re backwards, and we love Trump and coal.

I believe that [Democrat] Senator Joe Manchin doesn’t reflect what the people of West Virginia want to do. The biggest problem is that he’s not representing us, he’s representing his own interests.

The people in West Virginia are so good, that’s what's so frustrating about national news. In West Virginia you can't drive down a two-lane road without waving at every car that goes by. If not, people think you're an a**hole.”

Suzan Erem, 58, farmer and executive director of the Sustainable Iowa Land Trust, Iowa

“I transplanted here in the 1980s to go to college and learned about family farms and the crisis we were in then, when there appeared to be plans for corporate America to make Iowa look like one big cornfield. And they succeeded. Thirty years later, I came back and there it was.

Almost all of the family farms are gone. I was still in love with Iowa but it wasn’t the state that I fell in love with. But I moved back and got involved in organizing an effort to reduce the cost of farmland permanently, to grow sustainable food.

We started the Sustainable Iowa Land Trust (SILT) to put an end to farm crises by taking land that grows table food off the market for everyone except other farmers who do the same thing.

I’ve been immersed in food farming and all the issues around land use in Iowa in the last ten years. I planted an orchard of Asian pears, Japanese walnuts, native elderberries, and Haskap berries. I thought, ‘fruit trees in Iowa, even with climate change how bad could it be?’

But there are a certain number of hours every year that those fruit trees need to be under 45 degrees [Fahrenheit]. And I’m beginning to discover that might not happen in a few years. We’ve already had some winters that it was hard to count that many hours under 45F.

It’s ironic to say that I live in Iowa and want it to be colder but if that’s the way you’ve planted, that’s what you’re counting on. We need a certain number of “chill hours” every winter for the trees to sleep so they’ll do what they need to, when it’s time to work. I’m starting to worry that’s not happening.

The other thing in Iowa that a lot of people didn’t hear about was the derecho with 140mph sustained winds [in August 2020]. It’s called an inland hurricane and so highly unusual that nobody was ready for it.

We were lucky that as few people got hurt, but the property damage was unbelievable. I was part of a chainsaw crew helping take trees down off houses. I remember somebody saying, ‘When I watched TV during Katrina and other hurricanes down south, I thought it was exaggerating to say it would take years to recover. Now I see what they mean. It’s going to take years to recover from this.’

Most of Iowa was in drought for much of this year and I don’t think it’s going to get any better. However I still think that Iowa is one of the places where US climate refugees are going to end up. All the forecasts are that our weather is going to be better able to sustain human life than most of the continent.

It’s happening slowly but farmers and landowners are starting to understand the power of planting fruit and nut trees and berry bushes, not only to feed Iowans but to affect climate change. Historically, [farmers] only thought of trees as in the way, or as lumber or firewood.

My friends at the Savanna Institute in Madison, Wisconsin have a vision to perennialize 50million acres in the Midwest. They, and University of Missouri’s Agroforestry Center, are providing resources for landowners to plant tree crops like chestnuts that can live 2,000 years. Once [trees] are in the ground you’re not disturbing the soil, you’re running animals through them to graze, and sequestering carbon.

I am uplifted by the notion that more and more people in the Midwest are understanding the benefits of perennial crops. I think the research from the Land Institute in Salina, Kansas on perennial wheat, and trials in Iowa and Minnesota, are nothing short of revolutionary. These things are going to be crucial if we want to feed our people and cool the planet. We have to find a new way to grow food. I don’t want to squander the resource of this beautiful soil.

In Iowa you can grow anything, and we’re going to be able to year-round now with hoop houses, solar energy and geothermal. I’m convinced that with the right people and the right capital, we will be able to transform this landscape and it’s going to be a lot friendlier for the climate, and much more resilient.”

Geoff Mohan, wilderness travel guide and environmental journalist, California

“Like a fair number of people out here in California, I’m native to the East Coast but I’ve been here for over 20 years. In that time, I've done a lot of outdoor recreation including helping to instruct a wilderness travel course for the Sierra Club.

I guide groups of backpackers out to wilderness areas, predominantly in the Eastern Sierra, but also in other areas of California. I'm also a journalist and recently left the Los Angeles Times where I was for 20 years. I was environment editor at one point and also covered a variety of beats, many of which had to do with natural resources and the environment.

I notice more changes in California that seem to be irreversible. I'm constantly coming back from trips that were affected somehow, either by fire, an old fire scar, drought, massive tree mortality, or other phenomena.

The [wild]fires in the Sierra Nevada tend to be on the western slope, starting in the foothills and racing up into the higher mountains. This year, for the first time, two fires crossed all the way over the crest and into the eastern Sierra.

I do most of my backpacking in the far eastern ranges of these national parks so there is the sense that it won’t affect me. But this year and last, smoke descended on very remote regions. All of these effects are local now and anywhere you go, you’re not going to escape it.

Choosing a different part of the Sierra, which is a 100-mile mountain range, is not going to help. Every trip out there has a bit of sadness, that it’s slipping away from us.

Many people that I take [hiking] are well-versed in larger environmental issues but I do think they come back a bit shocked and chagrined, maybe a little saddened by the damage that they see. I wouldn’t say that it’s ruined but it’s no longer this unalloyed experience of seeing what wilderness can be in its pure state.

Some [hikers] do come back thinking of how they can reorient their lives, to try to go after some of these bigger forces that seem so overwhelming such as climate change.

The forces acting on [the landscape] are now so much greater than what we might have conceived of 50 years or a century ago when we simply were looking at trying to keep land public, and from being privately exploited.

I go fly-fishing when I can and this year it seemed like the snow simply evaporated. It didn’t really melt off and trickle into the streams. They were running at a level that you would expect in the middle of a hot summer instead of roaring as they usually do in the spring. Places that should have been wet, and where you would be devoured by mosquitoes, were without any noticeable insects whatsoever. Guides were shaking their heads, they couldn’t figure out what was going on.

There’s a water crisis statewide. They’ve not yet resorted to mandatory cutbacks for municipal water but I know a fair number of people in the agriculture community who did not get water allocations this year, and had to resort to wells that are getting progressively deeper.

I have, at times, considered leaving southern California at a minimum. Heatwaves are lasting longer, and after a while it can become kind of unbearable. I’m middle-aged, and I’m thinking of retirement and the latter half of my life. I wonder whether I should be spending it here or in a more temperate environment?

We have to come to grips with the fact that we simply don’t have enough water for the amount of people we have on the land, and the things that we’re doing with the land. We need to make some very hard decisions because we simply can’t rely on miraculously having a better winter, and more snow to replenish reservoirs. I think those days are over.

It’s really tough to make hard decisions on not just how we use water in our cities but how much we allocate to farming, what type of crops we farm, and where we sell those crops.

Many people are leaving California but I don’t think there’s a mass exodus. I think you look at the numbers, it’s about what it has always has been. But we have to figure out the best way to live in an arid environment. -And that’s one that really isn’t, for the most part, suitable for agriculture, without damming and redirecting water.

And it’s not suitable for large cities ,in many respects. We really have to rethink how we settle out here in the American West for the next 100 or more years.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News