Oxford University vows not to make same mistake with Covid vaccine as it did with penicillin

Oxford scientists are at the forefront of the global race to end the pandemic, with the Prime Minister hailing the group as being “on the verge” of creating a successful vaccine.

But the university’s vice-chancellor has vowed that it will not make the same mistake as it did with penicillin in the 1940s.

Prof Louise Richardson said that when drawing up an agreement with the pharmaceutical giant AstraZenica over the manufacture of the vaccine, the university did not want to be party to any kind of “profiteering".

However, they also did not want to “repeat the mistake of the early 40s when Oxford academics discovered penicillin but handed all rights off to American companies”.

Addressing Oxford's governing body this week, Prof Richardson explained: “We required that any partner would agree that a vaccine, if proven effective, would be distributed at cost for the duration of the pandemic, and in perpetuity in the developing world.

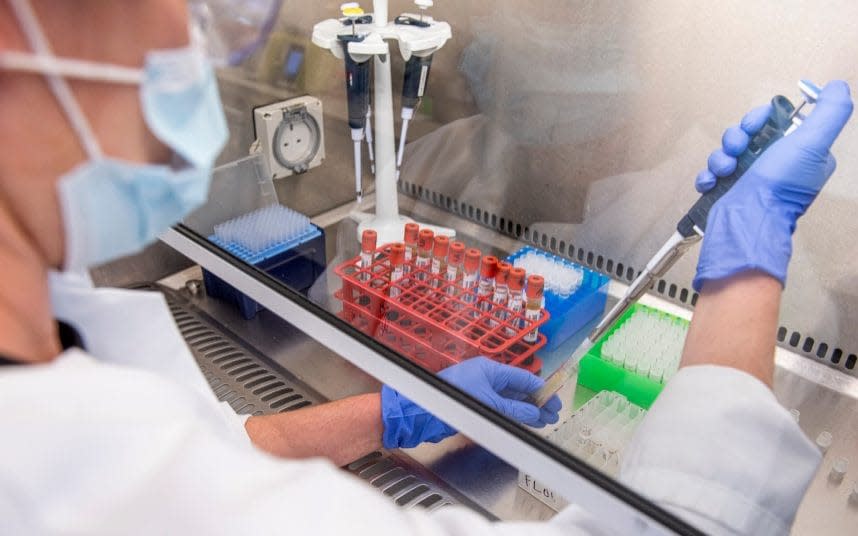

Watch: EU steps up real-time testing of vaccines

“AstraZeneca agreed and are now overseeing trials around the world and manufacturing at risk so that if the vaccine proves effective, distribution can begin immediately.”

While the antibacterial properties of penicillin were discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928, the next major breakthrough - to create a medical application for the product - did not come until the middle of the Second World War.

Howard Florey led a team at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology in Oxford that worked out how Fleming’s discovery could be used to produce antibiotics on a mass scale.

But wartime Britain was unable to produce penicillin on the scale that was required, so Florey made a secret visit to America 1941 to drum up interest.

Pharmaceutical companies in the United States grouped together to develop a high capacity industrial process which was capable of large-scale production of the drug.

Prof Richardson praised scientists at the Jenner Institute for acting with “lightning speed” in January.

She described how Prof Adrian Hill and Prof Sarah Gilbert, who had been working on the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, believed their work could be adapted to develop a vaccine for Covid-19.

“The University immediately agreed to provide a £1 million underwrite from the recently established Strategic Research Fund to enable the team at the Jenner Institute to ramp up their work,” she said.

“We judged that, if the venture proved successful, other funding would follow, as indeed it has. “Government, international organizations and generous private individuals, who contributed over £27 million, have invested in Oxford’s vaccine.”

She made the remarks during her annual speech - known as the Oration - which typically takes place just before the start of each academic year.

Watch: Inside a Chinese coronavirus vaccine factory

The Oxford vaccine has successfully passed through Phase 1 and 2 trials with results showing that it is safe and effective in triggering an immune response involving both antibodies and T cells. Phase 3 trials are now underway.

This week Boris Johnson announced that Britain's most vulnerable people will be prioritised when a vaccine for coronavirus is rolled out.

The head of the Government's vaccine task force has previously warned that the British public had a "misguided" perception of the programme's aims and suggested that fewer than one in two would be inoculated.

The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation has published a draft list showing who is likely to be at the front of the queue for a jab when a coronavirus vaccine is approved in the UK.

The list named older adults in care homes and care home workers as the first group, followed by those aged over 80, over 75, over 70 and over 65.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News