Oxford vaccine mix-up came from scientists misreading the strength of Italian manufacturers' supply

A mix up with the Oxford vaccine came about because their scientists had misread the strength of a dose sent over by Italian manufacturers, it has emerged.

An investigation by Reuters found that scientists at the institution were given clearance to give participants in the vaccine trial a dose of around half the strength because their tests had shown that the batch was much stronger than anticipated.

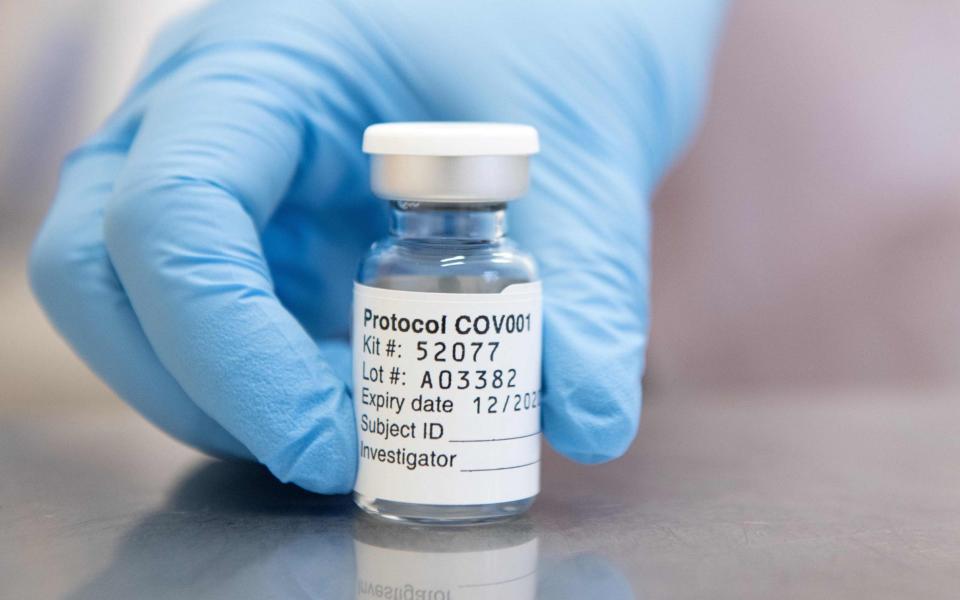

The shipment, batch K.0011, had undergone a quality check by the Italian supplier, IRBM/Advent, using a genetic test to determine the viral content of the vaccine.

According to Oxford University’s documents, when the consignment arrived in May the scientists ran their own analysis using a different method and found that the batch seemed more potent than the Italian manufacturers had found.

Trusting their own test results, the Oxford trial team was granted permission by the regulator MHRA to reduce the dose of the vaccine injected into participants from this batch.

However, Reuters have reported that documents published in The Lancet journal show that Oxford researchers had made an error in their testing.

IRBM/Advent told the news agency that the measuring mishap was “the result of a change in the testing method”.

The Lancet documents showed that a common emulsifier had been used in the mixing of the vaccine, which meant it interfered with the ultraviolet-light meter used by the institution to test its strength.

As a result, the participants in the trial received a much lower dose of the vaccine when Oxford scientists believed they were administering full doses.

The half doses, when followed up with another full dose booster, were 90 per cent effective and much higher than the 62 per cent of the two full doses, despite not being tested on anyone over 55.

The documents, however, do not mention whether AstraZeneca were informed by the Oxford researchers when they discovered the error, but say that the regulator was contacted for permission to change their testing method to the same one used by the Italian company.

“The decisions about dosing were all done in discussion with the regulator. So when we started the trial, we had some discrepancies in the measurement of the concentration of virus in the vaccine,” Andrew Pollard, the Oxford trial’s chief investigator, told the Telegraph.

When asked for more information on why the regulator granted their request, the MHRA told the Telegraph that it “cannot say anything further due to this being commercially sensitive information”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News