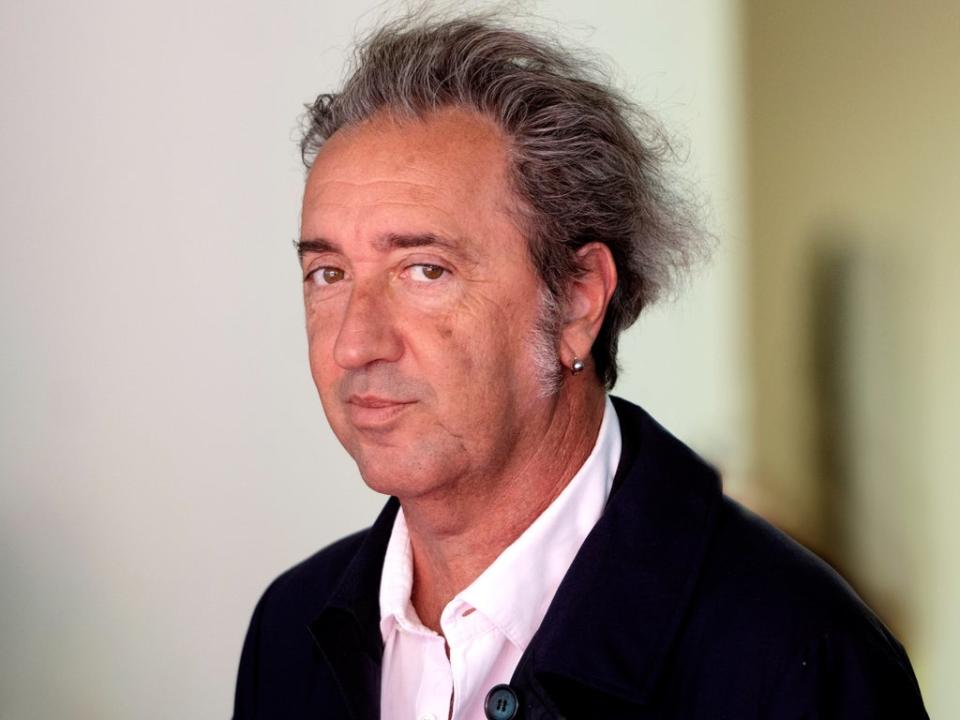

Paolo Sorrentino: ‘What worries me is the scepticism about these wonderful aspects of our life, like sensuality and eroticism’

If Napoli FC had not signed Diego Maradona, and Paolo Sorrentino had not been offered tickets for an away game at Empoli, he would have spent the night of 5 April 1987 with his parents at their ski house in the Apennine mountains. In all likelihood, he would have breathed in the carbon monoxide leaking from a faulty heater, like they did, and died, like they did, a month before his 17th birthday.

It is only now, at 51, two decades into a career that has brought him an embarrassment of acclaim and every award you’ve heard of – an Oscar, Baftas, Golden Globes, the Cannes Jury Award, lots of money from Netflix – as well as plenty you haven’t, that Italy’s greatest living director has tackled the cataclysm that defined his life. The Hand of God (È Stata La Mano Di Dio) is a fictionalised retelling of Sorrentino’s adolescence in Naples, named for the Argentinian footballing genius who inadvertently saved his life. Unsurprisingly, it is easily Sorrentino’s most personal work, a coming-of-age tale in which a happy childhood in southern Italy gives way to tragedy. It is also his best film since his 2013 masterpiece, The Great Beauty.

“I’ve been thinking about it for a long, long time, but I’ve always been sceptical about the possibility of turning the story into a film,” Sorrentino tells me over coffee during the London Film Festival. In trainers and jeans, with a ring in his left ear, and sideburns creeping down his cheeks, he has the rumpled piratical look of a guitar teacher giving the first lesson of the day after a late night at the jazz club. He understands the questions in English, and sometimes answers them that way, but more often than not relies on a translator. It was Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma, he says, which was based on the director’s childhood in Mexico City, that gave him permission to commit his own experience to film: “I realised that a personal, private film could tell a universal story.”

The Hand of God fictionalises the young Sorrentino as Fabietto Schisa, played by the newcomer Filippo Scotti. He is a thin, dreaming boy, in stonewashed jeans and short-sleeved shirts, who ambles the streets with headphones round his ears blaring English new wave. His mother Maria is played by Teresa Saponangelo and his father Saverio by Sorrentino’s longtime collaborator Toni Servillo, for once relegated to a supporting role. There’s a cool older brother, Marchino (Marlon Joubert), and an unseen sister, who in a running gag is eternally in the bathroom. Despite Saverio’s occasional infidelity, the Schisas are a happy family and the early scenes in The Hand of God are full of vivid, joyful tableaux of life with family and friends: boat outings, football games, long lunches under the pergola. Naples of the late 1980s is not a salubrious place, but it has a chaotic sense of community. Paolo’s father, like Saverio, worked in a bank, and the Sorrentinos were firmly middle class. The Schisas’ neighbours include a snooty family who fall victim to a memorable prank by Maria, and an ageing baroness (Betty Pedrazzi), who comes to play a surprising role in Fabietto’s development. Compared to the baroque exuberance of some of Sorrentino’s earlier films, The Hand of God has a calmer energy.

“The content is very different from my previous films, so I had to turn my style upside down,” Sorrentino says. For the first time, he didn’t work with his usual director of photography, Luca Bigazzi. “It demanded a much cleaner approach, with less artifice from camera movement, lighting, all of that. Aesthetics were not my main concern. The locations were my locations.” Domestic textures are rendered with nostalgic specificity: the clothes, the cars, furniture. Fabietto seems set for a professional role, perhaps following his father into the bank, or some comparable profession.

Then Maria and Saverio sit down side by side on their weekend away, nod off and don’t wake up. In the hospital, the doctors tell Fabietto and Marchino that it would be better for the boys not to see the bodies. Fabietto tears furiously around the waiting room. Let me see them, he says. Seeing, and not seeing, becomes a motif. The referee does not see Maradona’s handball against England. Do you see me, asks the woman who takes Fabietto’s virginity. For the first time, Fabietto begins to see the possibilities of film, despite the family only having four films at home. All the filmmaker can do is see.

“[Seeing] expresses the essence of my job, my profession,” Sorrentino says. “He is obsessed with the possibility of seeing. When he cannot see he suffers a lot. We filmmakers exist for our ability to see.”

The later stages of the film explore the irony that if it were not for his parents’ deaths, Fabietto, like Sorrentino, would never have found his way into filmmaking. He meets the (real-life) Neapolitan director Antonio Capuano (Ciro Capano) who goads him into proving that he has something to say. Eventually, at dawn, Fabietto confesses that they wouldn’t let him see his parents after they died. Why go to Rome, the older man replies, when he has everything he needs right here in Naples? In another scene, Fabietto visits a gangster friend who has ended up in prison, where they discuss different kinds of liberty. It encapsulates the orphan’s paradox, of being free of his parents’ demands but imprisoned by their sudden disappearance.

“I think the highest degree of freedom can often come with a lack of freedom,” Sorrentino says. “When freedom is freely available you end up not doing what you were going to do with it. That was the position I found myself in at 17, when I found myself completely free but not knowing what to do. The only way I exploited my freedom was becoming a filmmaker. My cultural background would have prevented me otherwise: It would have been completely crazy and forbidden.” As one character says: “Cinema’s not good for anything, except as a distraction from reality.” What could be more important?

If The Hand of God is a departure for Sorrentino, it also riffs on familiar themes: the lost and longing; the young and the old; religion; architecture; the sea; dancing; ruined nobility. His debut was in 2001 with One Man Up, a comedy and his first work with Servillo, but it wasn’t until three years later that he broke through with The Consequences of Love, a drama in which Servillo played a mob accountant harbouring dark secrets. Sorrentino’s natural exuberance contrasted with Servillo’s sangfroid to create a poised, dark meditation on what gives meaning to life. He and Servillo, in heavy prosthetic make-up, teamed up again for 2008’s Il Divo, about the corrupt Italian prime minister, Giulio Andreotti. Along the way Hollywood noticed. Sorrentino’s next film, This Must Be the Place (2011), his first shot in English, starred Sean Penn as a rock star hunting down a Nazi.

Then in 2013 came The Great Beauty, which won the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar and secured Sorrentino’s reputation. Servillo starred as Jep Gambardella, a dandyish literary journalist in Rome who celebrates his 65th birthday and wonders about how he has spent his life. This is a city so beautiful that it makes tourists faint just to look at it, a place where it is quite possible, for a certain milieu, at least, to party a life away among the fountains and piazzas without making anything of consequence. It’s a dreamlike vision, an unabashed celebration of Rome’s gleaming surfaces that shows glimpses of the sadness and corruption behind them.

In the light of The Hand of God, it’s notable how frequently surrogate parental figures crop up in his earlier work. There are prime ministers and presidents and mob bosses. In The Young Pope, starring Jude Law, and its sequel, starring John Malkovich, he takes on il Papa himself. Even Jep has an editor urging him to write more. In the absence of parents, Sorrentino’s characters often look to other sources of authority, who rarely turn out to be benign. His previous films tend to show the world through the eyes of men middle-aged or older, ready to ruminate on what has been. This is most explicit in Youth (2015), another film in English, in which Michael Caine and Harvey Keitel play lifelong best friends in their seventies, who reflect on their lives at a hotel in Switzerland. What’s different about The Hand of God is that while Sorrentino is exploring the events of his own life, Fabietto is just setting out. It’s the first time the director has told the story of a character younger than himself.

“I’m well aware of that,” he grins. “The films I’ve made in the past were prompted by my curiosity to explore different worlds, which were mysterious to me. Here it was the opposite, it’s the only world that I’m familiar with. I had to go for it in a very different way.” Key to the process was casting Scotti. “I was looking for someone without any specific qualities,” Sorrentino says. “I wanted a shy boy, like many adolescents are, who has not found his place in the world and feels uneasy with life.” Scotti bears more than a passing resemblance to another tousle-haired boyish actor, Timothée Chalamet, who also made his debut in an Italian coming-of-age drama set in the 1980s, Call Me by Your Name. “You’re not the first to have said that,” Sorrentino says, “but it’s purely coincidental. I haven’t even seen that film.”

Women have always had a central place in his work, often portrayed with unapologetic reverence and eroticism. Fabietto’s Aunt Patrizia (Luisa Ranieri) in The Hand of God is a case in point, a totemic beauty who strips naked in a memorable scene on a boat and serves as a vehicle for the dreams of the men around her. (In an early scene she is impregnated by a saint. It makes more sense in context.) But Sorrentino has not escaped feminist criticism. In the current cultural climate, his unabashed sensualism feels old-fashioned if not altogether passé.

“It has become more difficult,” Sorrentino says. “There have been very just claims, but they have caused a confusion about what you can and cannot do. I’m lucky enough that I can do what I want, but what worries me is the scepticism about these wonderful aspects of our life, like sensuality and eroticism. The portrayal of a woman by a male director cannot exist without a dreamlike quality. For me, women are the dream that I have of women. They are wonderful dreams, but I realise that in my portrayal there might be aspects that aren’t appreciated by women themselves.”

The Hand of God will have a limited UK theatrical release before arriving on Netflix on 15 December. Maradona saves Sorrentino’s life. The film gives the sense he also saves Naples, bringing hope and joy to a city often derided as the grit in Italy’s boot. After the fateful match in the 1986 World Cup, one of Fabietto’s uncles says the “Hand of God” incident is retribution for the Falklands war. In England, I say, Maradona’s handball is viewed somewhat differently.

“I know,” he laughs. “When I came to England in 1987 I was advised not to mention Maradona because of how he was perceived. But that’s life. What’s injustice for some is safety for others. And while the ‘Hand of God’ was the purest act of cheating in a game, 20 minutes later Maradona scored the goal of the century. It was a historic game. So much so that one year, as a birthday present, my wife gave me a photograph of the ‘Hand of God’ goal autographed by Peter Shilton.” Maradona died before seeing the film. “It’s a big regret,” Sorrentino says. “One of my dreams was to show him the film.”

He won’t be drawn on what he’s doing next, although there are persistent rumours it will be something with Jennifer Garner. Whatever it is, it won’t be about another president. As well as Il Divo, there was Loro (2019), in which Servillo took on Silvio Berlusconi. “I am done with the political,” Sorrentino says. “I did it when I was young and ready to fight. In Italy, making a film about a living politician becomes very stressful, way beyond the cinematic object. I’m no longer ready to deal with all of that.”

“I’ve had a lot from filmmaking,” he adds. “My ambitions have changed. They’re smaller now. I devoted the first 20 years of my career as a director focusing on how to walk on stage. I think it’s now proper for me to focus the next 20 years on how to exit the stage.”

As Fabietto is embarking on his new world in film, his brother urges him to enjoy the present. It’s August, he says, why don’t you just stay on the beach? Fabietto says he can’t do that. He has to keep moving. Is happiness possible when you’re standing still, or only when you’re in motion?

“Neither,” says Sorrentino. “I’m pessimistic. I believe only children can be happy, when the responsibility of the world is on someone else’s shoulders and you’re completely carefree. I lost that lightheartedness sooner than most people because of my personal tragedies. At that point, you lose all possibility of being happy.”

In Sorrentino’s work, beauty never lasts, and neither does happiness. The two are entwined. Whether it’s the Colosseum crumbling outside your balcony, the gilded apartment of some fading aristocrats, a political ideal, a gorgeous face, skill with a football, a friendship, an innocent childhood, your parents: everything ends in ruins. Look around you, he tells us: these fleeting moments of grace are all we can hope for. But maybe they will be remembered one day, or captured on film.

Read More

Ridley Scott is wrong to blame millennials for his box-office bomb – but he’s right to be angry

Stephanie Beatriz: ‘Bisexuals are so often presented to be super promiscuous’

Halle Berry as a beaten-down MMA fighter? Spot the similarity

Paolo Sorrentino’s The Hand of God dazzles as much as it confounds – review

Kevin Williamson interview: ‘The Scream movies are coded in gay survival’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News