People Power: If we want to defend our democracy we must expel the Lords and replace them with the people

MPs voted last month, after years of procrastination, to repair the crumbling buildings in which they work. The restoration won’t get going until 2025, but it’s a start. Sadly, they failed to take the chance to begin an equally necessary overhaul of Parliament itself.

What if they had? Given the chance to remake Parliament in 2018, what would we do? How could the system be modified to increase the day-to-day influence of British citizens – nearly 47 million of whom are eligible to vote?

Here’s how. We start in the obvious place, at the least democratic, southern end of the Palace of Westminster. We expel the occupants. And we give the House of Lords to the people.

We cannot put everyone in the chamber; nor can we sensibly put everything to referendum. What we could do, though, is create a People’s Chamber, whose 400 members, randomly conscripted from the electoral roll as jurors, would be a small, representative sample of the population as a whole.

The details are negotiable. Here’s one hypothetical version. Everyone eligible to vote is also eligible for selection by lot to serve in the chamber for a fixed term of, say, four years. Service is compulsory, well-paid and prestigious. The People’s Peers can wear ermine and, if they want, use titles; the financial rewards are comparable to a sizeable lottery win.

The chamber’s functions remain the same: scrutiny, endorsement, revision, occasional delay. The great and good have vacated their seats, but much of their expertise can remain. The new peers’ four-year terms include a six-month period for training. (The intake would eventually be staggered.) Expelled members of the old chamber can choose between a severance package, or, if they prefer, paid employment as trainers or specialist advisers for their randomly selected replacements.

It would all take a bit of organising. So did National Service (which disrupted 130,000 lives a year rather than 400 every four years). And while some people might resent the call-up, their displeasure would be worth living with. As with jury service, there would be the option of seeking exemption or postponement. But the whole process – selection, plea, outcome – would be public; and with luck most people would prefer to do their civic duty than to risk the social stigma attached to dodging it.

The overall running costs might be higher than those of the current House of Lords. It would be money well spent. The prize would be a second chamber whose legitimacy could not be questioned: a chamber that, finally, was no less democratic than the Commons, yet did not challenge its supremacy: not more legitimate, or equally legitimate, but differently legitimate. The two chambers would complement one another – and the legislation enabling the reform could make it clear that the Commons had primacy.

Every voter, as a potential member, would have an emotional stake in this new chamber, and thus in Parliament. It would be a chamber of “us” rather than “them”; and, as a result, would not seem remote or out of touch. It would be a chamber of our peers.

Would it work? There would be drawbacks. We have all seen how easily people power can go rogue, in Twitter mobs or in votes for Boaty McBoatface. But the mere creation of the chamber would remove the need for anti-establishment gestures.

As for mischief, experience suggests that randomly selected citizens who are given decision-making responsibilities usually take them seriously and exercise them wisely. We see this all the time in juries. It has also been demonstrated repeatedly in experiments in deliberative polling conducted by, notably, Professor James S Fishkin of Stanford University and Professor Robert C Luskin of the University of Texas at Austin.

These experiments are, of course, quite different from suggesting that the deliberations and scrutiny of a representative cross section of the public could replace the current functions of the House of Lords in their entirety – but it is only a medium-sized leap from one thought to the other.

The key point for the moment is this: however much our prejudice tells us that the average citizen, given a role in Parliament, would be thoughtless, feckless and ignorant compared with the average ermine-clad peer of the realm, the evidence suggests that, placed in contexts in which it is clear that their judgements matter, members of the public typically rise to the challenge.

If you think otherwise, it’s arguable that you should be opposed to democracy itself. You should certainly be against trial by jury. But you should also apply the same question to the chamber’s current occupants. Do you really believe that, collectively, the massed members of today’s House of Lords offer a better source of wise, impartial judgement than a random cross section of the electorate?

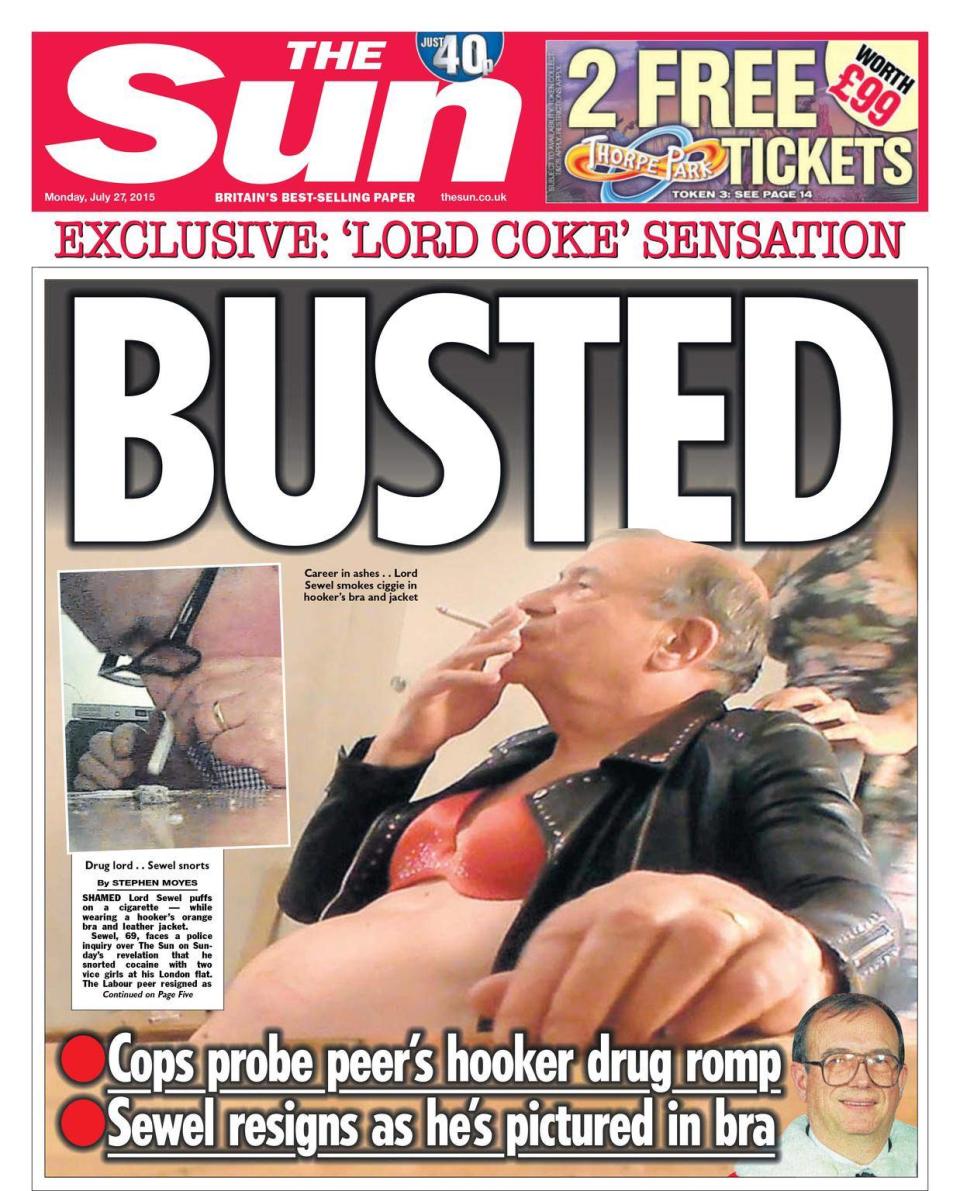

Ninety-one of them, remember, are there mainly because of who their parents were. Twenty-five are there because of their prominence in organised religion. Around 500 are beneficiaries, to some degree, of party political patronage. Most are drawn from the same gilded sub-sets: career politicians, academic high-fliers, company directors. Many have significant outside financial interests. Three-quarters are men. Their average age is 69. Such a house may be clever and experienced. But is it fit to speak for the nation – or merely for the establishment?

In a randomly selected house, everyone – rich, poor, old, young, educated, uneducated, pushy, shy, high-flying, under-achieving, innovative, traditionalist, male, female, white, non-white – will tend to be represented, in proportion to their democratic weight. And so will voters, whose preferred parties or candidates have failed to win first-past-the-post elections to the Commons. In John Adams’s words, the assembly is “in miniature an exact portrait of the people at large”.

A further virtue is that the enlisted members are not driven by ambition: power has been thrust upon them. They are independent of government and, since they cannot seek re-election, have no incentive (unlike MPs in the Commons) to put short-term political advantage before the long-term national interest. Collectively, they are likely to understand the priorities of ordinary voters, and their loyalties are to nation, not party.

I can already hear the scorn of parliamentary sophisticates mocking the naivety of my proposal and complaining that I don’t understand the full complexities of how Parliament works. Maybe I don’t. But I do understand that, on its own terms, the current upper chamber works reasonably well. I accept that – among the party stooges, hereditary fools and hard-faced businessmen who have done well out of globalisation – it has a substantial contingent of experienced parliamentarians and real-world high achievers, without whose skilled revision of legislation we would be a worse-governed nation.

I don’t deny that, over the past couple of decades, there have been many occasions when the House of Lords has behaved with more wisdom and principle than the Commons. I even accept that the chamber’s weak legitimacy may have helped it to find a useful role as a trusted servant of government: helpfully independent-minded but not a threat.

But all this is to look at the question from the wrong place: from inside Westminster. Look at it from the outside, and bigger issues claim the attention. It’s the system as a whole that’s dysfunctional. A large part of the electorate feels that Parliament does not share its priorities.

* * *

This is not a proposal to replace expertise with ignorance. It is a proposal to redistribute the power to influence government. All the ingredients of my proposed People’s Chamber are already in use in the existing House of Lords. Outside experts advise, as witnesses to select committees; so, to a degree, do ordinary citizens.

Appointed and hereditary peers, some of them “great and good”, can choose to draw on these contributions, along with their own expertise, when deliberating and voting. In the system I propose, the greatest and best former peers would be paid to join outside experts in giving advice (plentifully, I hope), while citizens would be in the chamber, with the power to use the advice as they saw fit. The aim would be for the quantity and quality of expertise in the equation to remain the same.

Only the power would shift. But it would truly need to shift. An advisory citizens’ panel would change nothing. A citizens’ chamber with decision-making powers (even limited ones) would change everything.

This isn’t the first time such a system has been proposed. Political theorists call it “sortition”. It was used successfully in ancient Athens and at different times in Italian city states such as Florence and, later, in parts of Switzerland. In modern times it has been used, to varying degrees, for assemblies on constitutional reform in Canada, Iceland, Mongolia and the Republic of Ireland.

When I first tried to advocate it in print, nearly 20 years ago, the story ended up as The Independent’s April Fool item. But it has played a part in a number of significant crowd-funded assemblies, such as the hugely popular G1000 citizens’ summits in Belgium and the Netherlands. Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary-general, recently endorsed it, and there has barely been a year in the past three decades when a political thinker somewhere in the world hasn’t proposed it – often as part of a wider programme to incorporate elements of direct democracy into existing representative systems.

As I write this, the British Government is engaged in the most ambitious national undertaking since D-Day. I won’t try to hide the fact that I consider the whole enterprise a disastrous mistake. But my views may well be wrong and are in any case irrelevant. The point that matters is the relationship between, on the one hand, the democratic expression of the people’s will at the ballot box and, on the other, the course the nation takes.

The ordinary voter is prevented from taking part in constructive day-to-day deliberation or policy adjustment. If we vote for something, and then decide that our original decision needs revising, we have no mechanism for doing so beyond throwing out the entire government – often blaming it, unfairly, for having done precisely what we once told it to do.

And if we vote for something in a referendum, we appear to have no way of modifying our decision ever. Yet it turns out that voters’ elected representatives are equally constrained, since they are not allowed to reach conclusions that don’t conform with the previously expressed “will of the people”.

There is, in fact, no admissible option for constructive day-to-day deliberation – and, as Anthony King and Ivor Crewe have shown in their 2014 book The Blunders of Our Governments, lack of deliberation is one of the main drivers of state incompetence.

* * *

In nearly 20 years of banging on about the potential benefits of a People’s Chamber, I have grown used to two big objections to the idea. The first is that random selection would produce representatives who weren’t up to the job. The second is that, simply, it ain’t going to happen.

My usual response to the first is that we already have a system that produces representatives who aren’t up to the job: not all of them, by any means, but as many as you’d expect in a comparably sized random population sample.

For a long time, however, I found the second objection persuasive. No matter how neat the idea, there really couldn’t – could there? – be the slightest chance of its becoming reality.

Now I’m not so sure.

One of the great paradoxes of modern British politics is that, in an age of rising populism, there is no corresponding popular enthusiasm for Lords reform. Why not? In today’s collective, people-friendly discourse, we despise the privileged, reserving special contempt for the titled. We scorn fusty traditions. We have a horror of unfairness. Many of us resent the status quo in all its manifestations. Yet we tolerate the House of Lords.

The idea that such a chamber should speak and legislate for the nation is laughable. Yet raise the question of reform and you’ll be met with an instant and near-universal glazing over of eyes. There is one powerful reason for this: the alternatives on offer are usually only marginally better. Dozens of options for Lords reform have achieved some kind of political traction over the past century or so. Two models for selecting members have dominated: election and appointment. The proportions have varied: wholly appointed, wholly elected, or some mixture of the two. But the proportions aren’t the problem. It’s the methods that are flawed.

Lack of popular appetite for Lords reform as envisaged by the political professionals isn’t quite the same as lack of appetite for a more radical kind of reform – a kind that would directly challenge the power of the Westminster establishment. And one of the good things about living in an age of hi-tech populism is that simple, sexy, people-friendly ideas can occasionally catch the public imagination so comprehensively that they force themselves to the top of the political agenda.

Could this really not happen with a proposal to sweep away a chamber that’s a democratic embarrassment and replace it with one that gives ordinary people a direct role in Parliament?

I think it could. Yet even that would not be enough. Such a reform could take place only with the consent and the will of the current establishment: the very people whose grip on power would be loosened by a People’s Chamber.

Yet it isn’t entirely unthinkable. The Liberal Democrats and Labour are committed to Lords reform as part of the wider goal of, in Jeremy Corbyn’s words, “the democratisation of public life from the ground up”. The Conservatives, on the other hand, find themselves – fairly or unfairly – associated with privilege. But intelligent Tories realise this, and history suggests that their party has a tenacious instinct for reading the writing on the wall – and, if necessary, performing whatever ideological somersaults seem necessary to ensure its survival.

If the Tories claim the proposal for themselves their toxic reputation as the nasty, people-hating party of the privileged could be neutralised at a stroke, and popular hunger for change could be used (as before) to re-energise the party rather than sweep it away. Rival parties could hardly object – yet the Conservatives could claim the electoral rewards. And if the rival parties wish to neutralise that threat, they must beat the Tories to it...

* * *

“People are tired of experts,” said Michael Gove when campaigning for Brexit. He was right, but he missed a bigger story: people may be tiring of politicians, too. Not all people or all politicians but many of both. How could they not? Westminster is the setting for a system of parliamentary democracy in which the educated elite manage the democratic mandate of the ignorant masses. But if the masses have rejected the educated elite – precisely because they are educated, elite and, for good measure, cocooned in the Westminster bubble – where does that leave the system?

The people’s trust is broken – and the political professionals who are blamed for breaking it are in danger of joining the liberals and the experts, on the wrong side of history. For the first time in centuries, the legitimacy of Parliament itself is in doubt.

For those of us who believe that, for all its flaws, our representative democracy is worth defending, the question of Lords reform is becoming urgent. How can you defend as “democratic” a system in which our futures are decided, in part, by a chamber that is no more democratic than the Garrick Club? A reformed system that required the wholehearted support and active involvement of ordinary people would be a different matter. Its democratic legitimacy would be beyond question, and the whole system would be stronger as a result.

The People’s Chamber would be a workable solution to a real, urgent and obvious danger. There is a rising tide of populism in Western politics: a non-specific clamour for direct democracy that threatens to submerge representative democracy in the tyranny of the mob.

It is folly to ignore that tide. It is folly to yield to it. The wise course is to react constructively, neither denying facts nor surrendering to them. Somehow, we need to channel those waves of popular discontent.

My rough proposal for Lords reform offers a simple form of channelling. Others may be able to suggest a better form. But we have to do something.

Richard Askwith is a former executive editor of The Independent

Yahoo News

Yahoo News