‘Did we work through hangovers? Most definitely!’ The stars of This Life on their era-defining show

Almost 25 years ago, a bunch of fictional wannabe lawyers moved into a house together in south London to start studiously preparing for their budding careers. Or rather downing bottles of white wine, shagging indiscriminately and stealing each other’s yoghurt.

This Life was real life, and yet somehow it felt revolutionary. It broke with the moralising TV conventions of the time: people went out to take ecstasy only to end up having a great time; gay characters introduced TV viewers to the art of cruising; interracial couples didn’t spend their entire screen time discussing being interracial couples.

Instead of signposting the pressing social issues of the 90s, they were woven into the daily life of these infuriating, self-absorbed and yet lovable characters. The result was perhaps the definitive TV portrait of the hedonistic, apathetic era with a soundtrack – all Britpop and trip-hop – to time-stamp the era. And it slowly accrued the devoted audience it deserved.

Now it is back, on BBC Four and iPlayer, for former fans to binge on and twentysomethings living in house shares to discover for the first time. So raise an ill-advised extra glass of soave as we join the old cast and writers to relive the madness.

Amy Jenkins (writer/creator): The controller of BBC Two at the time, Michael Jackson, was desperate for the channel to be cooler. He had this idea of a show about young lawyers, and I had briefly been a lawyer, so my agent put my name forward. I had to say: “I’m not interested in the law, I’ve just left it.”

Sam Miller (original director): Amy was really in touch with the house-share situation, and what that involved for young people.

Amy Jenkins: I watched a lot of what I call precinct shows – vets, doctors, detectives – and the bits I loved were when the characters just talked to each other. I didn’t give a shit who did the crime, but I liked the relationship between the two cops in The Sweeney, for instance. So I said to Michael: “Fine, it can be about lawyers, but we’re never going to go inside a courtroom.”

Jack Davenport (Miles): The writing was really different from most television. If you took a load of drugs, you didn’t necessarily die immediately. If you had unprotected sex, you didn’t automatically become HIV positive. People liked it because there was no moralising. If you’re 22, you’re going to make some really bad decisions, but that’s OK. Relax.

Amy Jenkins: I worked on developing the characters. One part of me aspired to be Milly – organised, wise and in a steady relationship – but another part of me wanted to be carefree, witty and as glamorously tragic as Anna. Then there was Miles, who stood for entitled, handsome, unavailable men. Andrew Lincoln’s character, Egg, was meant to be the new lad – loving, but also into football. I dreamed up these total cliches, really. But people really responded to them. We went quickly to script, and then it got made. My agent was saying: “This never happens.”

Cyril Nri (Graham): This script arrived in the post. I sat down on the toilet to read it and didn’t get up again until I’d finished it. I had never read anything like it. I remember one scene with Milly and Anna chatting in the bathroom while Miles is waiting to get in … it was real life. You come across something like that maybe once every 10 years, when you think: “I have to be in this. I don’t care how. I just have to be in it.”

Amy Jenkins: I didn’t set out to capture the zeitgeist. I was just keen to talk honestly from my experience of life.

Sam Miller: Amy delivered something that felt so personal and candid. But Tony Garnett [the executive producer, who died in January] realised that the show would live or die by the casting. We wanted to find unknowns – people who hadn’t really done much – and then make sure the relationships between the characters worked.

Jason Hughes (Warren): I had a few auditions. On my third one, there were lots of potential Eggs, potential Millys etc. They were pairing people up and putting them together, like speed dating.

Jack Davenport: I auditioned, like, six times. They put me in a room with a lot of different Annas. It went on for ever, but, because I had nothing to compare it with, I thought that was normal.

Sam Miller: We pushed Jack quite hard. We were exhaustive about finding the right combination of people.

Jack Davenport: I’d love to pretend that when I met Daniela [Nardini] the heavens opened and I declared: “This is going to be a legendary television pairing!” But, no. I was just thinking: “I’ve already done this six times … either give me the job or leave me alone.” I’m pretty sure Daniela felt the same way.

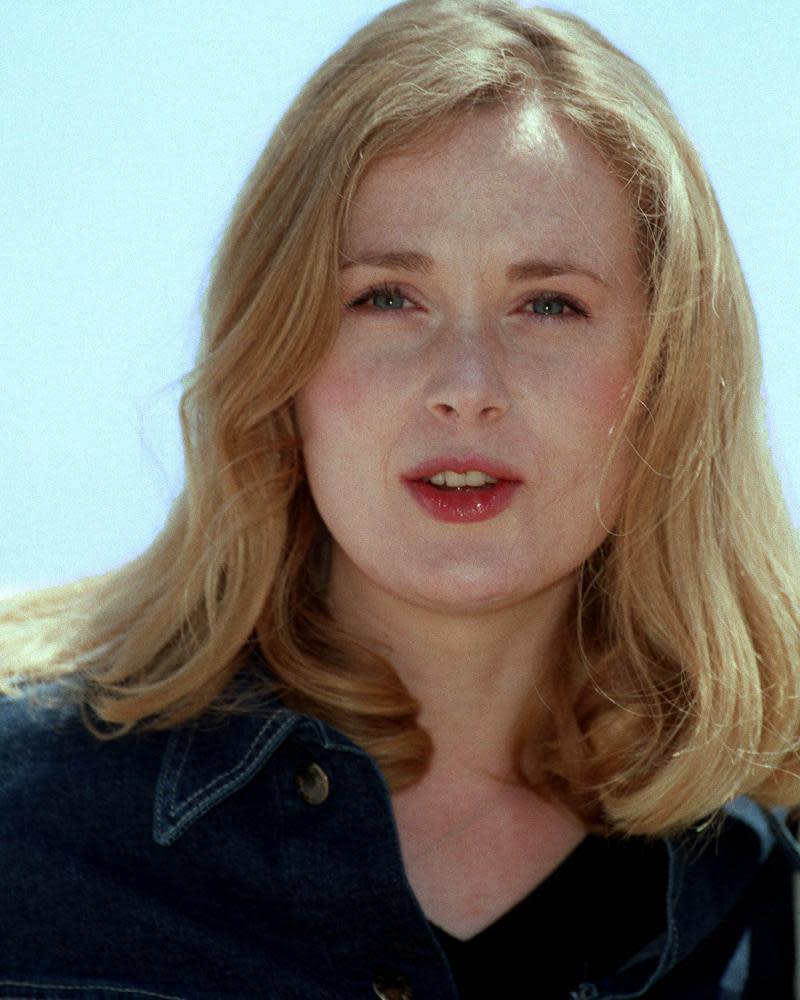

Daniela Nardini (Anna): I only had one interview and only met one Miles. I came to London, and heard I’d got the part pretty much straight away.

Jack Davenport: It’s a measure of the totality with which Daniela consumed the role that I couldn’t even tell you who any of the alternative Annas were or what they were like.

Amita Dhiri (Milly): I’d left drama school, and given myself three years to make it. Lots of people were telling me that I’d just end up being “woman waiting on a train platform in a sari”. Then a friend at the actor’s co-op I was part of told me I’d be great for the part of Milly. Just to see the name “Milly Nassim” on a script and to have her talk about things anyone my age would, rather than, say, how difficult it was to be Asian in society or how strict my dad was … that really stuck out.

Jack Davenport: We were all so scared. Like: “Fuck, we’ve all got really big parts and lots of scenes to do.” All of us had barely left university or drama school. We were like the characters, arriving in the adult world and living in our first places in London.

Sam Miller: The house the characters lived in was a real building just south of Southwark Bridge. Having a real house where people could look out the windows was important for the feel of the show. When you eat away at those little truths, it becomes harder for something to feel real.

Amy Jenkins: In the first episode, Anna tells Egg that she hates the Beatles. I’d actually said the same thing to Michael during my first meeting with him, and that was when his ears pricked up. It must have been a really outrageous thing to say to someone of his generation. I didn’t actually hate the Beatles. I was just sick of the way that if you talked about Oasis or Blur or whatever, then that generation would tell you how derivative they were.

Sam Miller: We wanted the show to feel different from what went before. I’d done Jed Mercurio’s first show, Cardiac Arrest. This Life was a chance to develop that kinetic shooting style. We broke a lot of TV rules. I remember shooting a scene in bed at night and the cameraman saying: “We can’t transmit this. It’s far too dark.” But it was night-time … it had to be dark.

Daniela Nardini: The camera was like another character – it would whiz around the room and pick up stuff we didn’t even know we were doing.

Jack Davenport: There were all these intense, emotional scenes where we’d be trying desperately to squeeze out a couple of tears for the camera, and then we’d watch it back and all you can see is the back of your ear.

Sam Miller: We had some viewer complaints about dizziness at the time. I thought that sometimes it got misinterpreted. We never shook the camera for the sake of it. It was always generated by the action.

Jack Davenport: The average page count for a regular scripted drama is about five or six a day … we shot 11 or 12. That’s why the wobbly camera technique was used.

Natasha Little (Rachel): I don’t remember there being much rehearsal. It was get up, try it, shoot it.

Jack Davenport: I remember my friends from college going: “Wait … a car comes to your house? And picks you up? And takes you to work?” And I’d go: “Yeah, it’s crazy, isn’t it?” And then six months later, when you’re getting up at 4.45am day after day, you’re like: “There’s a car outside to take me to work because these hours are insane.”

Amy Jenkins: The characters were all based around people in my life. I think that times have changed when looking at a character like Egg. It was much more radical back then not to go into a job for life. Now, we expect people to get McJobs or be entrepreneurial – so perhaps he seems a bit wet and not that special.

Jack Davenport: With Miles, I realised that the more I leaned into his essential twatness, the better things would be. Amy had met her fair share of insufferable, entitled, ex-public schoolboys who had a kind of cluelessness, which in some ways could be, I suppose, briefly charming if you were feeling charitable. Essentially, though, he was a complete git.

Daniela Nardini: I enjoyed the underlying tension and sexual attraction that ran through both series with Miles. But I also enjoyed playing the sides to Anna that were more vulnerable. She was very lost in some respects. Even though she gave over this image of being supremely confident, at the heart of her was a lot of insecurity.

Amy Jenkins: Anna was one of the first messy, damaged, interesting, independent women on telly.

Daniela Nardini: The part spoke to me at that time in my life. I hadn’t really seen a young woman depicted in that way before. She behaved a bit like a lad. She could certainly put the booze away. And you hadn’t really seen a woman behaving sexually in that way before, either. But to then also see a woman as ambitious as she was felt really fresh.

Amita Dhiri: Everyone talked about how uptight and cleanliness-obsessed Milly was, but I liked her a lot. I could see completely where all her frustrations came from with her relationship and career, and I loved her friendship with Anna. That friendship was there in real life. It could be quite boysy on set, so we bonded as the two girls.

Amy Jenkins: The idea for one of the gay characters, Warren, came from my housemate. He was known as “Richard the Priest” because he had studied to be a priest. Then he turned into a total clubbing fiend – the party priest!

Jason Hughes: Initially, I thought: “Blimey, this will be a big challenge for me,” because I’d never done anything like that before. I really wanted to make him a real person and not go for any of the obvious cliches.

Amy Jenkins: I was really, really disappointed that they didn’t cast a gay man. It was a problem for me at the time, although Jason is such a sweetheart and it totally worked out.

Jason Hughes: The gay community was absolutely marvellous about it. They were so pleased to be represented in a way that was truthful. There was the odd person who came up to say: “It should have been a gay actor playing your part,” but 99.9% of the gay community were incredibly supportive, and most thought that I was gay. You can’t get a better compliment than that.

Jack Davenport: Miles was pretty homophobic. Back then, it was still very easy for someone of Miles’s background to very unthinkingly hurl some belittling slur at someone, not because he was some dyed-in-the-wool gay-hater, but because he was a silly little boy.

Jason Hughes: Warren would get uptight about things such as his yoghurt going missing. His life was really ordered because he was trying so hard to fit in. He was desperate to remain in control of everything and of course that brings you into conflict when you live with other people.

Jack Davenport: One of the very few bright spots of the last 20 years has been the way the stigma around not being heterosexual has changed. Did This Life contribute towards that? It’s not a metric anyone can prove, but, in as much as any television show can bring about social change, it did very elegantly address a lot of hot-button social issues.

Amy Jenkins: I got a couple of incredibly touching letters from young men saying: “To see a gay man portrayed like that on television really changed things for me.” I felt as if I’d contributed something that was actually valuable.

Jason Hughes: I found all that so touching. Younger gay men out there, maybe 18-25 years old, were writing about how they had watched the show with their parents, and it had made it so much easier for them to talk to them about being gay. They said that without the show they might not have come out.

Amy Jenkins: Warren starts the first series having therapy. With those scenes, I was looking for something that hadn’t been done on television before. But it wasn’t intentionally pioneering. I had been to therapy. People were doing it, but it hadn’t reached TV screens yet. It was seen as a bit of a saddo thing and I wanted to make it more ordinary.

Jason Hughes: In Britain, there was this view that therapy was something Americans did. But of course people in this country did go to therapists; we just didn’t talk about it. Those scenes were fun, but for some reason they were always shot at 2am when everyone else had gone home.

Amita Dhiri: In many ways, TV hadn’t moved with the times. I’d grown up in Brighton, without a big Asian community … that’s not to say race wasn’t a part of my life, but other things were more pressing on the day-to-day level for us second-generation immigrants, such as who had eaten the last yoghurt.

Amy Jenkins: In those days, if a character was Asian on EastEnders, then their Asian-ness would be a big part of their story. I wanted race to be in there without comment.

Cyril Nri: Race wasn’t ignored, it was just subtle. So Graham and Milly being that organised, there’s a reason for that … it just wasn’t mentioned explicitly. And the jobs were not quite as top-level [for the nonwhite characters] as, say, Miles’s job – because of his father and connections. The show was progressive, racially and sexually.

Amy Jenkins: Right at the beginning, we got a terrible review in Time Out. They were trying to be the cool newspaper in London, but they soon realised public opinion was against them. They actually wrote a retraction at around episode eight saying that they now understood the show and that it was great.

Cyril Nri: It was a sort of underground find because it went out on a Tuesday evening, then had a funny repeat on BBC Two on Saturday night. Young people were discovering it after coming back from the pub.

Amy Jenkins: Tony wanted the show to be “discovered”. There were no ads or anything like that. That’s a very perilous policy to take, but it worked.

Jack Davenport: People felt like they owned it, and that’s why they loved it so much.

Amy Jenkins: There was a lot of Britpop being played and Portishead were on all the time. That had nothing to do with me. Ricky Gervais was actually the music supervisor. I did love all the music he picked.

Sam Miller: The music we used was just the music the characters were listening to on the stereo in the house – as if it were their actual taste and choices. We weren’t using music to tell the audience how to feel … that still feels fresh, doesn’t it? Having said that, there’s a scene with Miles up in his bedroom when he’s sad, and his life is a wreck, and you can hear Radiohead’s Fake Plastic Trees coming through the floorboards … that was a beautiful moment.

Amy Jenkins: We were told we were only allowed to have three swearwords an episode or something. And there was the famous rumour that Michael Jackson got cold feet at one point and went into the edit himself to take two seconds off the blowjob scene. I think it’s probably true.

Jason Hughes: One famous line for Warren is when he says: “Right, I’m off to get some cock!” I thought that was hilarious. Just a cracking line. I was delighted that I got to say that on national television.

Amita Dhiri: With the sex scenes, one rule I always made for myself was: if it’s part of the story then I’m willing to do it, but if it’s gratuitous then no. They were awful to film, though. Really awful. You’d worry what you were doing, and worry what the other person was doing … we all got embarrassed.

Amy Jenkins: I remember being rung up by the Daily Mail. They said: “We really object to all the explicit sex in This Life.” What I should have said was: “Well I really object to the Daily Mail.”

Amita Dhiri: It had to be real. If I was getting undressed, I would make sure I never took my tights off in an alluring way. I would just take them off like a woman would take her tights off. There was no soft focus.

Daniela Nardini: We did a scene where I went out with Egg’s dad and took ecstasy. I’d never done ecstasy in my life. Anna was much wilder than I was.

Cyril Nri: I would hate to say that most of the cast had a predilection for drink and drugs, but I would say that the production certainly had a way of spotting them and getting them involved.

Daniela Nardini: There was a fair amount of drinking involved. I remember going back to Jack’s mum’s house and drinking a lot of gin and tonics while we went through the day’s events.

Cyril Nri: A lot of the partying indicated in the script was performed in real life. Did we work through hangovers? I’m not sure I should give that away, but I would say … most definitely! I actually stopped drinking during This Life. I think for me it all got a bit too much. I felt like: I can either carry this on until it goes too far or I can stop.

Jack Davenport: I was forever at Andrew’s or Jason’s, or all of us were out together in the pub. When you’re 22, you can get away with having gone to bed quite late and getting up early to work, especially when in the scenes you’re shooting you’re meant to be three sheets to the wind. But it wasn’t like we all rolled in reeling every morning. Even a 22-year-old can’t do that for long.

Amy Jenkins: I never actually went on set. They didn’t want me there. They didn’t want me to contribute to the casting or anything like that. There was a policy of “hold the writer at arm’s-length or she’ll get in the way and make problems”. It’s not like today, where the writer is the creator and the show runner. Tony insisted on bringing in other writers, and there was no writers’ room. I loved Tony. He really changed my life and he was a great man, but I got very pissed off with being treated like just another cog in the works. I was also being offered some really nice jobs to work with some top directors at the time. So I left.

Jason Hughes: I left the show midway through series two. That was perhaps not the best decision I’ve ever made in my life. But I was a young, naive man.

Natasha Little: Joining in series two felt like coming into the cool gang. I wasn’t even cool enough to have watched the first series when it aired, and then when I did I was like: “Oh blimey, it’s really good and they’re all really cool.”

Amita Dhiri: The relationship between Milly and Rachel was all about passive aggression, where you can’t put your finger on what you don’t like about someone, and so if you call them out, you will look like the bad person.

Natasha Little: I remember during filming everyone saying how awful Rachel was. I genuinely couldn’t see it. I really liked her. I just thought, why wouldn’t you just be pleasant to the people you’re working with? Later, when people started saying she was evil, I just thought: “Well, I don’t think she is. I’m just going to get more entrenched into making her nice.” I don’t think she thought of herself as annoying.

Amita Dhiri: Milly ends up frustrated with Egg and has an affair with her boss, O’Donnell. He has all the power in that relationship. You could say it was a portrait of 90s feminism, but has anything really changed? In terms of the casual arrogance of a certain type of man, I don’t think things are any different. But women’s attitudes have changed. Women who are Milly’s age or younger now feel they have a greater stake in society.

Daniela Nardini: The second season builds to a climax where Miles ends up marrying Francesca despite his feelings for Anna. I suppose if we’d got together it would have been a happy-ever-after ending. But I think the audience would have seen through that.

Jack Davenport: Should Anna and Miles have got together? Are you really asking me this in 2020? They’re made-up characters. How should I know? But if we’re going to play that game then: no, of course they shouldn’t have got together … it would have been an absolute car wreck.

Cyril Nri: The filming of that final wedding suffered somewhat because of people’s imbibings. But it all got done and it worked brilliantly in the end … albeit with a couple of delays.

Jason Hughes: I came back for the final scene, when Milly and Rachel are fighting, and the wedding has turned into chaos. I’m wearing a Hawaiian shirt, a bit stubbly, with a nice tan compared with all the pasty housemates. They gave me just one word, and of course I can remember it: “Outstanding.”

Amita Dhiri: I had to persuade the director and the producer that Milly should punch Rachel for the final scene. They wanted a lot more hair-pulling, slapping, screeching and nails, but I didn’t think that was what a woman in that situation would do. When you get to the point when you’ve hit your limit and you don’t even care about who’s wrong or right any more, that’s what you’d do. I’m very proud of it.

Natasha Little: Did I wonder why I got punched? Yeah, I did.

Cyril Nri: The show only got really popular at around the end of the second series. I think Chris Evans or someone talked about it and suddenly it blew up.

Sam Miller: We had no idea it would be a hit. The BBC wasn’t sure about it, and at one point we thought it might be a disaster. It was only Tony who kept telling us we’d done something really good that would get copied and copied.

Amita Dhiri: Suddenly, we were getting stopped in the street, being asked to wear certain clothes or turn up to things.

Daniela Nardini: I remember we all got invitations to Elton John’s birthday party. I was thinking: “What on earth is going on?” It felt as if we’d become famous almost overnight. It was very peculiar and quite daunting – we weren’t prepared for it.

Jack Davenport: There was a think piece every other day in the broadsheets about whether the BBC would commission a third series. It was like, guys, really?

Daniela Nardini: I went to the Baftas with Jack and won an award. It was lovely, a really nice thing to happen, obviously.

Jack Davenport: For once, it’s not PR fluff to say that all of us adored each other. And still do. You could see that on the screen.

Daniela Nardini: If it were today, there would have been another series. I think it definitely had the legs. But we’d shot more than 30 episodes over about three years and were all ready to do other stuff.

Jack Davenport: Tony Garnett in his estimable wisdom remembered the greatest truth in show business, which is to leave them wanting more.

Amy Jenkins: And then we did a reunion show 10 years later. I don’t really know what to say about that. It was incredibly difficult to live up to people’s memories and expectations.

Jack Davenport: I loved filming the reunion, but we all knew perfectly well that it would get shat on from a great height because it was such a beloved thing. I thought the things Amy had imagined up for these characters were really funny and sort of quite plausible. But the whole point about This Life is that nothing ever really happened – it was quite Seinfeld-y in that respect – whereas in a 90-minute thing, you have to pack in a lot of incidents and plot twists.

Amita Dhiri: If anyone had asked me would you do a 10-years-on show, I’d have said to leave well alone. But there was such an appetite for it, and Amy was onboard, too. It was so much fun to make … but really what people wanted was what they already had.

Daniela Nardini: I was pregnant at that time, and really sick. For me, it was just a case of grit your teeth and get on with it. Everyone else had a better time, I think, but it didn’t feel the same.

Amy Jenkins: If it was a formula show, we could have just done the formula again. But it wasn’t and the characters all had to have moved on. I don’t know if it was any good. I know it wasn’t very well received and that people were disappointed, so I’m sorry about that.

Cyril Nri: The 10-year anniversary thing wasn’t as hot, but those two series were the perfect encapsulation of the 90s. These were all children who had come up through Thatcher and there was an enthusiasm that something new was about to happen with New Labour. But it also captured the apathy and despondency of that time.

Amy Jenkins: I just had beginner’s luck. I had that thing of being young and inexperienced, and not realising what I was taking on. I dunno … it was a kind of fluke.

Natasha Little: Even though we’re in this “golden age” of television – which I don’t disagree with – it’s still unusual to see shows take risks with an unknown cast and an untested writer. It was really brave, and the bravery paid off.

Amy Jenkins: To this day, commissioners say they want something like This Life. In truth, they’re loth to commission it.

Daniela Nardini: Playing Anna was a blessing and a curse because she was a difficult character to shake off. People kept trying to get me back into that kind of role, but there never was that same role. Anna was so sexually potent, and I think it was hard for a woman to break away from that.

Amy Jenkins: I look back on the characters, and I still like them. All of them. I’m surprised we’re still talking about them, though. The show’s a bit like Dad’s Army – it’s never going to go away!

Jack Davenport: It’s such a long time ago now that I can’t even recall most of what we did. I know that I had a lot of drinks thrown in my face, though, and that I probably deserved it.

Amy Jenkins: People occasionally come up to me and say: “You’re the reason I became a lawyer.” I have to say: “Oh my God. I’m so sorry.”

This Life is on BBC Four from 10pm and on iPlayer. Amy Jenkins (@amyturtleTV) will be answering questions about the show live on Twitter on 5 February from 10pm

Yahoo News

Yahoo News