The people’s vote: why didn’t we heed the lesson of 1979?

What would Britain look like if George Cunningham, known as the only backbench MP ever to have brought down his own government, had never lived? Would Scotland be less or more autonomous than it is now – independent, even? Would Jim Callaghan have seen off Margaret Thatcher in the 1979 election? Would the fleet never have sailed for the Falklands? Would the miners still have struck? The chances are that nothing would be very different: to cast Cunningham as the Gavrilo Princip of Thatcherism is an interesting idea, and a mistake. But what’s harder to deny is that if Britain had paid more attention to Cunningham’s most significant political achievement – remembering it as a lesson for a future referendum over Europe – we might all be much happier now.

A social club needs a two-thirds majority to alter its rules, but the UK can redirect its future by a margin of one

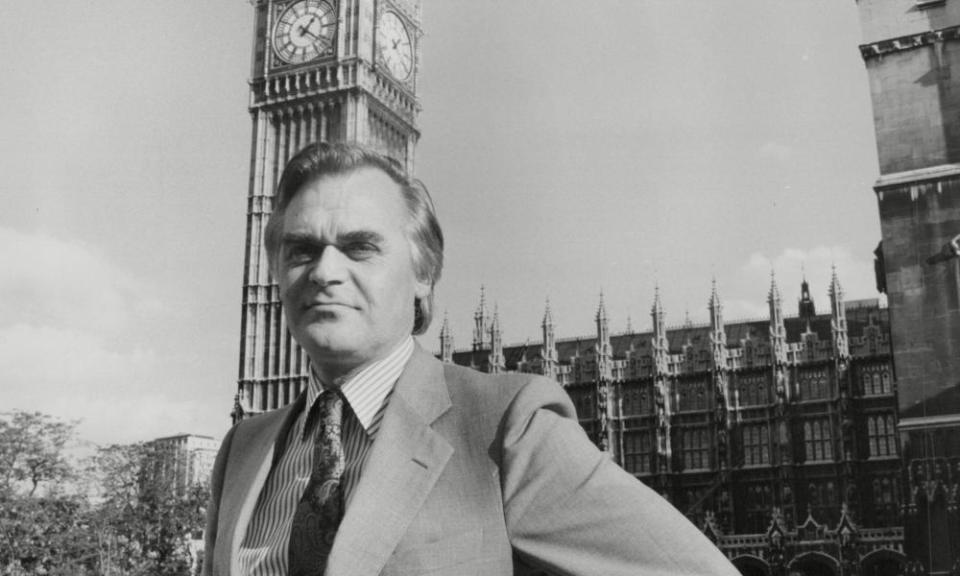

Cunningham, the former Labour MP for Islington South and Finsbury, died in July aged 87, after 15 years spent in a care home with Alzheimer’s. I never met him, and heard him speak only once. As the Labour MP for Islington South, he addressed a meeting of constituency residents who were protesting about the practice then known as “winkling”, in which property speculators bought up old houses and through a mixture of bribes and harassment, “winkled out” the sitting tenants so the empty property could be done up and sold for a good profit to young people who appreciated Georgian fanlights and cornices. This would be about 1975. I remember he seemed energetic and sincere. Nothing could stop the conversion of Islington’s picturesque old housing stock into homes for the middle class, but perhaps the protests reduced the harassment and made the bribes larger. What I knew about him was that we had gone to the same school in Scotland – Dunfermline High, where he was one among a small list of reasonably famous former pupils, none of them more famous than the ballet dancer Moira Shearer. But by the 1970s, Scotland was a long way in his past: he moved with his parents to Blackpool before he left school, attended universities in England, and after national service took a job with the Commonwealth Relations Office in London, where he joined the Labour party and won what was then Islington South West, in 1970.

Scotland, in the meantime, had changed. In Cunningham’s youth the Scottish National party had been viewed by most people as a harmless eccentricity, but it was now transformed by the prospect of North Sea oil. In the general election of October 1974, it attracted almost a third of the Scottish vote and sent 11 MPs to Westminster; seven years earlier there had been none.

The same 1974 election gave the Labour government a majority of three. Byelection defeats gradually eliminated this majority, so Labour had to form alliances and strike deals to keep governing – most significantly with the Liberal party (the Lib-Lab pact), but also with the Ulster Unionists and the Welsh and Scottish nationalists, who were promised the devolution of some political power from Westminster to assemblies in Cardiff and Edinburgh, each to be endorsed by a referendum.

Cunningham opposed devolution on the grounds that it would weaken the UK, and he introduced an amendment to the two bills that required them to be approved by 40% of the total electorate in Scotland and Wales as well as by a simple majority: 50% plus one vote of those who actually voted. The amendment had the support of Neil Kinnock and five other anti-nationalist Labour MPs from south Wales.

In Wales, the 1979 devolution proposal met a heavy defeat. Of the 58% of the electorate who turned out to vote, only 20% wanted a devolved assembly – equivalent to just under 12% of registered voters. The story in Scotland was different. In a turnout of 63%, 52% wanted devolution and 48% didn’t. The 52/48 ratio is now very familiar – the arithmetic of our present bitter and near-equal division over Brexit. But in 1979 another number, in Scotland at least, became more notorious: Cunningham’s threshold of 40%.

The majority of the actual vote translated into 33% of the potential vote. Devolution had to wait another 18 years – though this, perhaps, was a minor consequence compared with the fallout at Westminster, where the SNP demanded that Callaghan’s precarious government ignore the 40% rule; and then, spurning various complicated proposals to placate it, joined with the Tories in a no-confidence motion. The Tories were resolutely opposed to devolution of even the mildest kind. Callaghan described the SNP’s behaviour as “the first time in recorded history that turkeys have been known to vote for an early Christmas”.

The Ulster Unionists, not for the first or last time, offered the government support in 1979 in exchange for more money spent in Northern Ireland, but in the end only two of them (after an afternoon of whisky-drinking at Labour’s expense) supported the government, which became the first to lose office through a no-confidence motion since 1924. Five weeks later, in May 1979, Margaret Thatcher won the general election. Cunningham became notorious among some of his colleagues; in nationalist circles, he was more seriously reviled.

In retrospect, the plans for a Scottish parliament were modest enough – it would have met in Edinburgh’s old Royal High School – and it’s hard to imagine any lasting bitterness on the losing side if, in the absence of a 40% threshold, they had gone ahead. Nevertheless, Britain has taken a remarkably thoughtless approach to referendums in the years since: fundamental and far-reaching changes can be decided via the principle of a simple majority of 50% plus one. The humblest social club needs a two-thirds majority to alter its rules, but a large and complex society such as the UK can redirect its future by a margin of one. The loser’s resentment of the winner in this situation is almost a natural corollary.

In 2016, Brexit would have failed the Cunningham amendment: only 37% of the total electorate voted for such a revolution in Britain’s economy, its foreign relationships and its prospects. The choices on the ballot papers of a “people’s vote” have still to be fixed. But if this second referendum happens, it would surely acquire more legitimacy if the threshold for victory were set higher than its predecessor’s. A result that kept roughly to the 52/48 ratio but simply exchanged the victors – remainers in place of Brexiters – might have unpredictable consequences.

Cunningham’s 40% rule could have a role to play here. But despite the generally high-minded tone of the people’s vote movement, I am not holding my breath. Who wants to make the odds longer on victory?

• Ian Jack is a Guardian columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News