Philip Roth’s death won’t mean the end of great fiction. But we are losing our appetite for it

‘How could he leave? Everything he hated was here’ (Sabbath’s Theater)

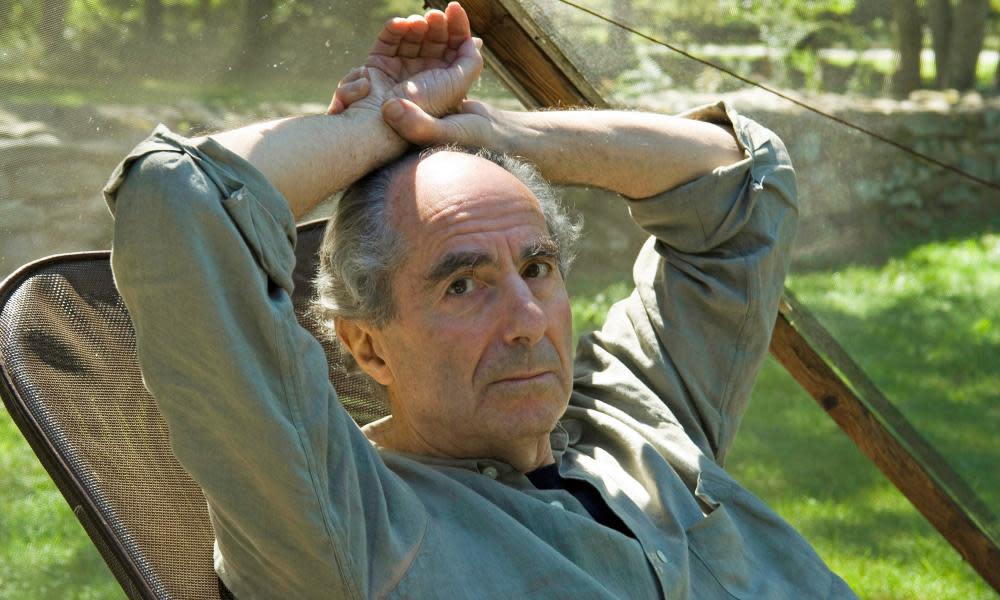

It’s hard to believe he has left. True, he called an end to his extraordinary production five years ago, but some silences are thunderous and the extracurricular buzz Philip Roth had always generated did not die down. Surely he was out there in rural Connecticut, the great monk of chicanery and excess, planning to blow our socks off one last time.

Now follows what he always dreaded and did so much to circumvent – the peeling back of artifice to find the truth, as though there is any truth to a novel other than itself. He didn’t trust his reputation to futurity. His strict categorising of his works into Zuckerman Books, Roth Books, Kepesh Books, suggests a nervous reluctance to let them make their own way in the world. Call it Mrs Portnoy’s revenge.

He attracted biographical intrusiveness from the start. It was the price he paid for being a superlative ventriloquist. Get mistaken for your characters and it isn’t only you the world maligns, it’s the very enterprise of invention. On it still goes, anyway. He was this, he was that – best of men, worst of men, a recluse, a performer, either way don’t shake his hand. I met him briefly once and didn’t enjoy the experience. I’m grateful for that. You don’t want a writer to charm you. You need to honour the art and forget the man.

Portnoy's Complaint (1969)

“Enough being a nice Jewish boy,” declares Alexander Portnoy, as he confesses the guilt-ridden mess of his life to his psychoanalyst. Fizzing with energy, sexual tension, and a whole lot of “whacking off”, it was an immediate scandal, an instant bestseller and made Roth a household name.

The Ghost Writer (1979)

Roth’s alter ego Nathan Zuckerman moves centre stage for the first time as he decides that the young woman he meets at the house of an eminent Jewish writer, EI Lonoff, is in fact Anne Frank. The panel selected The Ghost Writer for the Pulitzer prize, but were overruled in favour of Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song.

American Pastoral (1997)

At a high school reunion, Zuckerman is told the sad story of Seymour "Swede" Levov, the older brother of a former classmate. Roth explores the American political turmoil of the Vietnam war years, with Zuckerman reimagining the life of Swede, a promising young man who thought he'd achieved the American dream – until his life began to unravel around him.

The Human Stain (2000)

Another Zuckerman novel: here Roth's alter-ego observes as his neighbour Coleman Silk, a professor and dean at a nearby college, is accused of racism by two students and forced to resign his job after the subsequent uproar. Considered to be a (very) lightly veiled criticism of campus liberalism, the novel also considers sexual politics, with Silk beginning a relationship with an illiterate janitor working at the college while the US president Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky scandal is dominating headlines.

The Plot Against America (2004)

What if the aviator Charles Lindbergh had been elected president of the US? Roth goes back to the 40s to imagine an America that never entered the second world war, signed a non-aggression pact with Germany and began persecuting Jews. Rooted in Roth’s Newark childhood, this fascistic takeover seemed utterly plausible in the wake of 9/11 and is ever more urgent in the era of Donald Trump.

It’s for the art, then, that we should be grieving today. Roth’s death marks the end of a remarkably rich period of American fiction. I nearly said American Jewish fiction, but the distinction is redundant. In the period now closing, American fiction was American Jewish fiction. Roth, Bellow, Malamud, Heller, Mailer. For a host of reasons, their immigrant experience of isolation and self-betterment became the creative drive of America. Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be Jewish was very heaven. If we won’t see such a constellation again it is not because the stars won’t shine so brightly but because we have stopped looking.

Great writers won’t go away just like that, but great readers will. A decade or so ago, Roth himself rang the death knell: in the face of new distractions, he foretold, and as the screen edged out the page, our ability to concentrate on words would become a thing of the past. Maybe he was wrong; maybe the concentration a work of the imagination demands will miraculously find a way back. But it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that just as no novelist would again command the universal respect Dickens and George Eliot enjoyed so, after Roth, the sophisticated pleasure of embroilment in a tough text will find fewer takers. We descend a rung at a time.

In 2011, the publisher Carmen Callil resigned as a judge of the Booker international prize when her fellow judges voted overwhelmingly for Roth. The experience of reading Roth, she said, was akin to having him sitting on her face. I have to ask: need that be such a bad thing? How much breathing must a reader do? To change the metaphor, doesn’t the exhilaration of reading Roth at his best reside in being swept along by those swollen rivers of rage or exultation, those paragraphs of ferocious disputation in which one sentence powers up the next, probing the one before, provoking the ones to come, to the point where the act of keeping afloat becomes part of the exercise in intelligence the words demand.

Follow me, follow me, Roth demands, not in admiration for the pyrotechnics, but in order to arrive at last at justice. American Pastoral ends, marvellously, in the simplest of questions: “What on earth is less reprehensible than the life of the Levovs?” But we reach it, like spent swimmers on a strand, at the conclusion of 400 pages of relentless analysis of a society in which the life of the Levovs is found reprehensible. After the storm, the light. Roth earns his clarity through the courage to be dense.

If there’s a syntactical exactingness that recalls Henry James in the novels of this period, there’s also an ethical exactingness that recalls the Talmud. Roth’s Jewishness took familiar forms in his early books: the impenitent sinner, the loving son, the incorrigible joker. But it’s the fiery, rabbinical Roth, scholar and scourge of every new fad of priggishness and sanctimony, a holy litigant with a foul mouth, who argues the case for the Levovs and the Coleman Silks.

And men. For there is a case to be argued for men. And Roth risked preposterousness, and the usual charges, in arguing it. All I would say about that is that I wish so many of the women in his novels didn’t find so many of the men so sexually alluring. Bellow handled that kind of stuff more tactfully.

Sabbath’s Theater is the novel that bridges the sometimes too self-conscious naughtiness of the earlier books and the deep sonorousness of those that follow. Gone now, for example, the games of identity peek-a-boo. (I never much cared, myself, who was or wasn’t the real Philip Roth. Best to believe there wasn’t one.) Though Sabbath’s Theater is his most profane work, it is also the one that best balances profanity with the sacred. If you’re going to offend, offend religiously. The novelist who has Sabbath urinate into the grave of the woman he loves is unmistakably the same novelist who has Portnoy masturbate into everything, but the offender is no adolescent this time, and the offence is now an act of grieving worship. Before you harumph, take time to ask just what carnal love is and what part the body plays in erotic devotion.

Sabbath’s life-greed beats that of all his predecessors hands down. My Life as a Man has now become My Life as a Monster. Lear we allow to self-destruct. It’s not quite our business. Sabbath we beg not to humiliate himself one more time. But his life is an experiment in going beyond shame. “He felt an uncontrollable tenderness for his own shit-filled life. And a laughable hunger for more. More defeat! More disappointment! More deceit.” And then this meticulous assertion of life’s foulest energies, daring to associate purity with shit – “For a pure sense of being tumultuously alive, you can’t beat the nasty side of existence.”

The long war on decorousness is finally won. “How could he leave? Everything he hated was here.”

So did Roth, aged 85, change his mind? Did he fall sufficiently in love with life again to leave it?

Wrong question.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News