Philip Roth: US novelist hailed as the greatest of his generation

Philip Roth, whose sexually scandalous comic novel Portnoy’s Complaint brought him literary celebrity after its publication in 1969, would come to be hailed as one of America’s greatest living authors for the blunt force and controlled fury of his dozens of later works.

Roth’s 1959 debut story collection Goodbye, Columbus earned him the first of two National Book Awards. He would go on to publish 27 novels, two memoirs and several more story collections by the time he publicly retired from writing in 2012. His lifelong themes included sex and desire, health and mortality, as well as Jewishness and its obligations – arguably his most definitive subject, given the controversy surrounding his earliest works.

In later years, his focus shifted more frankly to the nation and its discontents, from the rise of Richard Nixon as a political figure in the early Cold War era to the sideshow of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal in what became known as Roth’s American Trilogy: American Pastoral (1997), I Married a Communist (1998) and The Human Stain (2000).

“He at once talked about America and American-ness, but filtered it through the history of the 20th century at large,” according to Aimee Pozorski, an associate professor of English at Central Connecticut State University who had written extensively about Roth.

“He wrote about the American response to the Holocaust, but also about its effects in Israel and Central and Eastern Europe,” Pozorski says. “He talked about the spread of, and simultaneous fear of, communism in the US but also considered cultural shifts in Prague during that time. He could write about these international issues because he was truly cosmopolitan, a global citizen who was grounded by American culture.”

She called Roth “the voice of his generation”.

A 2006 survey by The New York Times Book Review of the best books since 1981 found an astonishing six of Roth’s novels among the top 22. Well into his senior years, he continued to win the highest laurels of his profession with new, evocative works. In 1993, his Operation Shylock: A Confession won the prestigious PEN/Faulkner prize; in 1995, Sabbath’s Theater won the National Book Award; in 1997, American Pastoral won the Pulitzer Prize.

His appeal was not limited to elite critical circles, drawing such enthusiastic fans as Bruce Springsteen, the rock musician and fellow native New Jerseyan. Speaking of Roth’s American Trilogy, Springsteen once observed: “To be in his sixties making work that is so strong, so full of revelations about love and emotional pain, that’s the way to live your artistic life. Sustain, sustain, sustain.”

After The Human Stain, Roth sprinted to his career’s finish line with a remarkable decade-long kick, writing seven more books.

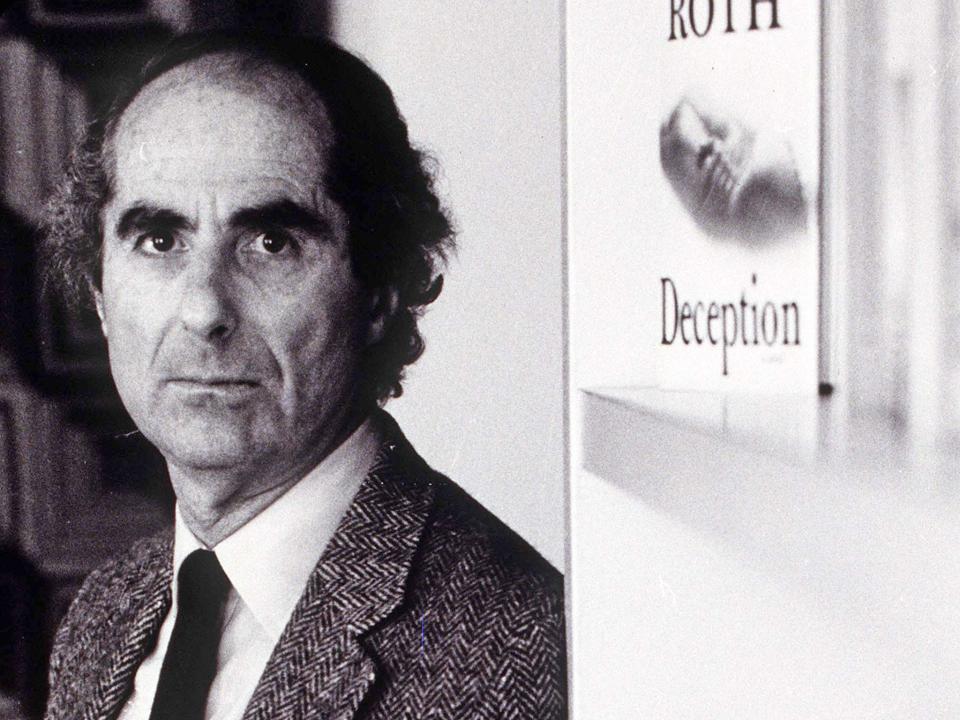

His topics were often autobiographical, yet so tantalisingly veiled that “Philip Roth” appeared in several novels. Roth relished blurring the line between fact and fiction; his second wife, the English-born actress Claire Bloom, felt betrayed when she read a manuscript of Deception: A Novel (1990), a brutally frank anatomy of infidelity that featured characters named Philip and Claire.

Roth removed Bloom’s name before publishing, but included an afterward with the figures arguing.

“To compromise some ‘character’ doesn’t get me where I want to be,” the book’s “Philip” says to the nameless English woman. “What heats things up is compromising me. It kind of makes the indictment juicier, besmirching myself.”

Roth’s 1988 memoir, The Facts: A Novelist’s Autobiography, was framed by his correspondence with one of his frequent fictional alter egos, Nathan Zuckerman. The author asked his creation for feedback.

“Don’t publish,” Zuckerman replied at the end of the memoir, delivering a harsh critique of the “real” Roth for all his blind spots and willful omissions.

Zuckerman, like Roth a Jewish writer assaulted by Jewish critics at the outset of his career, was one of several figures Roth returned to repeatedly in his fiction. The character was central in books from The Ghost Writer – the 1979 novel in which Zuckerman imagines he is married to the real Anne Frank (who secretly and miraculously survived the Holocaust) – to Exit Ghost in 2007, which found an irascible, ailing Zuckerman swapping his Connecticut retreat with a young Manhattan couple fleeing the city in fear.

Another frequent protagonist was David Kepesh, who was introduced in Kafkaesque fashion as a 6ft-tall mammary gland in The Breast (1972) and exited as the lusty, lonely intellectual of The Dying Animal in 2001.

Roth’s home town of Newark, New Jersey, also often figured in his work. His final novel, Nemesis (2010), vividly recalls the panic that gripped the city during the polio scare of the 1940s.

Philip Milton Roth was born in 1933 to first-generation Americans – Herman Roth, an insurance salesman for Metropolitan Life, and his wife, the former Bess Finkel. They were Jews who “were and were not religious”, and they “didn’t talk about the past. There was no remembering elsewhere,” he recalled in The Facts.

He winced when referred to as an American-Jewish writer. “Growing up Jewish as I did and growing up American seemed to me indistinguishable,” he wrote, also in The Facts. “I’d come from a small, safe, relatively happy provincial background – my Newark neighbourhood in the Thirties and Forties was just a Jewish Terre Haute.”

Roth left Newark for Bucknell University in Pennsylvania mainly out of restlessness, to escape the familiar home town and his father, largely motivated by the younger Roth’s blooming rebellion.

“I wanted something difficult and dangerous to happen to me. I wanted a hard time. Well, I got it,” Roth said in 1984.

At Bucknell, he edited the literary magazine, was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honour society and conscientiously began to find his writer’s voice, ruthlessly critiquing a colleague in print and discovering “a flash of talent for comic destruction”.

After graduating from Bucknell in 1954, he received a master’s degree in English the next year from the University of Chicago and served in the army for a year (largely behind a desk in Washington DC). He then returned to Chicago and taught English at his alma mater while writing fiction. An early admirer was novelist and future Nobel laureate Saul Bellow, who told an interviewer that Roth’s stories “showed a wonderful wit and great pace”.

In 1957, Roth’s short story “Defender of the Faith” was accepted by The New Yorker. The portrayal of a young Jewish soldier ignobly demanding religious loyalty from his army superior – also Jewish – angered critics who worried about negative depictions of Jews.

When Goodbye, Columbus was accepted for publication in 1958, Roth resigned his teaching post and moved to Manhattan, but the friction with his antagonists wasn’t over.

In 1962, Roth shared a panel with Invisible Man author Ralph Ellison and Italian novelist Pietro di Donato during a symposium at Yeshiva University. Again he was denounced by questioners who thought he was undermining Jews. Roth later recycled the incident in The Ghost Writer, and he frequently said the standoff was formative.

In 1973, Roth explained the double-edged sword of those early attacks: “I might turn out to be a bad artist, or no artist at all, but having declared myself for art – the art of Tolstoy, James, Flaubert and Mann, whose appeal was as much in their heroic literary integrity as in their work – I imagined I had sealed myself off from being a morally unacceptable person, in others’ eyes as well as my own.

“I think now – I didn’t then – that this conflict with my Jewish critics was as valuable a struggle as I could have had at the outset of my career ... I resented how they read me, but I was never able to complain afterward that they didn’t read me; I never felt neglected.”

Roth married his first wife, Margaret Martinson, in 1959. They separated in 1963, and in 1968 Martinson died in a car accident. The marriage was intensely difficult; Roth painted his wife as stifling and manipulative in The Facts, giving her the pseudonym of Josie. The marriage contributed to an extended period in the 1960s when the novelist said he was barely able to write. The gap from 1962 to 1967 was the longest he ever went between publishing.

A regimen of psychoanalysis led to the neurosis-filled Portnoy’s Complaint, the riotous tale of one young Jewish man’s anxiety and excessive masturbation. An early stab at the book was a play called The Nice Jewish Boy, which in 1964 had a trial reading at New York’s American Place Theatre with Dustin Hoffman. (The script didn’t work.)

“There’s always something behind a book to which it has no seeming connection, something invisible to the reader which has helped unleash the writer’s impulse,” Roth said of Portnoy in the 1984 collection Writers at Work. “I’m thinking about the rage and rebelliousness that were in the air, the vivid examples I saw around me of angry defiance and hysterical opposition. This gave me a few ideas for my act.”

Portnoy’s Complaint drew criticism from Jewish groups for its perceived ethnic stereotyping and from others for its sexual explicitness. But it also won praise from prominent reviewers for being playful and moving, a masterpiece on guilt. Writing in The New York Times, author and screenwriter Josh Greenfeld called it a “deliciously funny book, absurd and exuberant, wild and uproarious”.

If Portnoy made Roth a household name, it also generated enduring jokes at his expense that likened him to the self-pleasuring title character. The most memorable was uttered by novelist Jacqueline Susann, who remarked on The Tonight Show that Roth may be a terrific writer, “but I wouldn’t want to shake hands with him”.

The acclaim for the Ghost Writer trilogy – with the writer Zuckerman viewed as a very close stand-in for his creator through Zuckerman Unbound (1981) and The Anatomy Lesson (1983) – rescued Roth once and for all from the Portnoy reputation as a clown prince of sexual provocation.

“When all of those books were taken together, you had my story,” he said in the 2013 PBS documentary Philip Roth: Unmasked. Yet earlier he had said: “Nathan Zuckerman is an act. Making fake biography, false history, concocting a half-imaginary existence out of the actual drama of my life is my life. There has to be some pleasure in this job, and that’s it. To go around in disguise. To act a character. To pass oneself off as what one is not. To pretend. The sly and cunning masquerade.”

Beginning in the late 1970s and continuing through the 1980s, Roth and Bloom split time between America and London. (They married in 1990 and divorced in 1995.) In 1989, Roth left his longtime publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux for a $2.1m, three-book deal with Simon & Schuster – at the time a huge and risky sum, sceptics suggested, for such an intensely literary author.

If few American writers compare with Roth’s frank analysis of the male body’s desires and decline, it is because Roth wrote with near-unbearable clarity about so many of his own physical challenges.

Roth endured knee surgery and then a quintuple bypass in 1989, a period when he was addicted to the drug Halcion. That, in turn, triggered depression and emotional instability, as described by both Roth and Bloom (and as featured in Operation Shylock).

At 34 he suffered a burst appendix and then peritonitis, a condition that once plagued Roth’s father and killed two of his uncles. Back trouble hampers Zuckerman in The Anatomy Lesson; in real life it drove Roth to suicidal thoughts. In The Dying Animal, Kepesh’s autumnal lust is described with humiliating exactitude, a problem exacerbated, as in so many Roth books, by the presence of an apparently healthy and beautiful young woman.

Roth was admitted for psychiatric care in 1993, and Bloom writes in her memoir Leaving a Doll’s House that on the admitting form Roth cited health concerns and bad reception for Operation Shylock – a book featuring duelling Philip Roth figures during the Jerusalem trial of accused Nazi war criminal John Demjanjuk. In The New Yorker, John Updike had written that Roth “has become an exhausting writer to be with. His characters seem to be on speed, up at all hours and talking until their mouths bleed.”

In her own book, Bloom draws herself as caged by an often wrathful Roth, describing his emotional gamesmanship as “Machiavellian”. “Philip’s novels provided all one needed to know about his relationships with women,” Bloom wrote, “most of which had been just short of catastrophic.”

For decades Roth’s primary home and workshop was his late 18th century farmhouse in northwest Connecticut, where distractions could be kept at bay. His existence was described as austere and semi-reclusive.

“I’m like a doctor and it’s an emergency room,” Roth said in 2000 of his Connecticut seclusion. “And I’m the emergency.”

Roth’s powerful, probing, mocking literary voice didn’t translate to Hollywood, despite several attempts. A version of Portnoy’s Complaint (1972), starring Richard Benjamin and Karen Black, received scathing reviews. The Human Stain (2003) starred Anthony Hopkins and Nicole Kidman. Elegy (2008), based on The Dying Animal, starred Ben Kingsley and Penelope Cruz, and was seen as lacking Roth’s trademark ferocity.

“It’s a wonder that filmmakers continue to adapt Mr Roth’s work to the screen, which is largely inhospitable to tough, prickly and unappetising ideas and characters, especially in America,” film critic Manohla Dargis wrote in the Times review of Elegy. “It seems instructive that no great director has tackled this great writer, whether out of fear or shrewdness.”

Roth detractors included author Carmen Callil, who in 2011 noisily resigned as a judge of Britain’s Man Booker International prize when the three-person panel chose Roth for its award. “He goes on and on about the same subject in almost every single book,” Callil said. “It’s as though he’s sitting on your face and you can’t breathe.”

“Tell me one other writer who 50 years apart writes masterpieces,” replied fellow judge Rick Gekowski. “In the 1990s he was almost incapable of not writing a masterpiece – The Human Stain, The Plot Against America, I Married a Communist. He was 65-70 years old. What the hell was he doing writing that well?”

In the 2013 PBS documentary, Roth, by then routinely rumored as a candidate for the Nobel Prize, said, “In the coming years I have two great calamities to face: death and a biography. Let’s hope the first comes first.” In Exit Ghost, Zuckerman has nothing but scorn for the young biographer seeking to unearth long-held “facts” about EI Lonoff, the ageing, difficult, reclusive Jewish writer Zuckerman visited in The Ghost Writer.

Yet when Roth announced his retirement in 2012, it was soon revealed that the author was cooperating with biographer Blake Bailey.

“Am I Lonoff? Am I Zuckerman? Am I Portnoy?” Roth asked in a 1981 interview. “I could be, I suppose. I may be yet. But as of now I am nothing like so sharply delineated as a character in a book. I am still amorphous Roth.”

Philip Roth, novelist, born 19 March 1933, died 22 May 2018

© The Washington Post

Yahoo News

Yahoo News