Pink Floyd's The Wall: 'a bleak, manic and agonised album' – archive, 1979

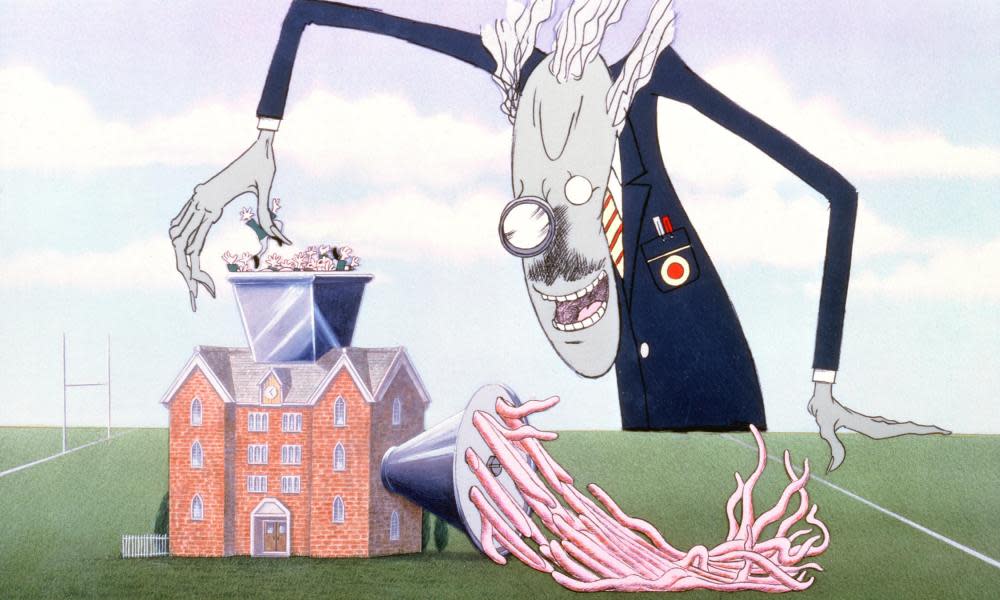

The Pink Floyd are not available for comment on their first recording in nearly three years, a bleak, manic and agonised double album simply called The Wall (Harvest SHSP 4111). They were told that due to an accounting problem they would have to leave the country, very fast, if they didn’t want to pay a gigantic tax bill. So they’ve gone, leaving their record company with no new promotional pictures or biographies, yet alone explanations of this quite extraordinary work, that comes suitably packaged in a forbidding, anonymous design of a wall (with Scarfe cartoons breaking through it inside the gatefold), and without even the title printed on the sleeve. It’s somehow appropriate for an album that will be a smash with analysts, dealing as it does with alienation, madness and death.

Related: Pink Floyd's The Wall film review – archive, 15 July 1982

The Floyd have dealt with such themes before, from The Dark Side of the Moon to Animals, but never with such bitter passion. This is a long, uneven work that seems to lose direction on the confusing third and fourth sides, and it veers uneasily between crazy indulgence and nihilistic brilliance. But shows that those members of the new wave who attacked the band because of their vast concerts and use of elaborate technology, had really missed the point. This album will either be praised or damned. It’s a strong, frightening statement that shows why the Floyd never were – yes, and are still not – redundant, in spite of their wealth and success, because they still question themselves and the world around them. Roger Waters, who wrote almost all of The Wall, has never sounded less complacent or more suicidal.

The first bombastic passage shows that he will be questioning his own role with the Floyd, rather than just the alienated society he sees about him. There’s a parody of Floyd’s famous stage-show special effects, and he asks “is this not what you expected to see?” The question is not answered until the song is repeated on side four, by which time his vision has become so wild that a neo-Nazi gang are on stage in place of the Floyd, checking “where you fans really stand” and taking gays, blacks and Jews from the audience. And that comes after a whole depressing life and death “Wall” saga. No, this is not easy listening.

The most accessible, central part of the work is contained on the first two sides. From the first sounds of a baby crying to the final suicide note, Waters describes the “wall” that he sees built around people, cutting them off from each other and leaving them frightened and lonely inside. As the wall is built and the figure inside gets more crazy, there are attacks on those he sees laying tile bricks — schoolteacher, mother, lover and wife.

Sound effects from bird song to random television noise build up the feeling of alienation, while the music uses the full range of the Floyd’s long-established talents, from grand melodic themes to gentle acoustic patches, held together by the mesmeric, jangling choruses of Another Brick In The Wall (in which a London children’s choir perfectly follows Water’s clipped vocals). Add to this some classic Dave Gilmour guitar breaks, and lyrics like “love turns grey, like the skin of a dying man” and the first two sides are a chilling Floyd classic.

But there are two more sides to go, from which one presumably concludes that the suicide wasn’t real after all, or that the “wall” theme is now being localised to the Floyd’s own problems. Side three includes a piece on the West Coast trendster who has everything but still gets no answer on the phone, a strange piece about Vera Lynn (complete with operatic chorus singing “bring the boys back home”) that presumably questions the disappearance of the cameraderie that existed in wartime, and an excellent song, Comfortably Numb, that leads back to the rock ‘n’ roll band theme.

The finale is a musical asylum. There are Nazis on stage in place of the band, there’s a pounding piece of paranoia Run Like Hell, a worryingly sick piece Waiting For The Worms that mixes the themes of performance, the wall and fascism with morbid fascination. As if that wasn’t enough, it’s followed by The Trial. The “prisoner is accused of showing feelings of an almost human nature” and the wife and mother reappear in an operatic sequence that I suspect sounds like listening to Lionel Bart during a very bad acid trip. It ends with Outside The Wall and (I think) some sort of hope.

The first section is brilliant, the second patchily fascinating, and I sympathise with those who find it all too bleak to handle. But the Floyd’s new work is frighteningly strong and genuinely experimental, and it quite overshadows all other British releases this month.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News