Police bracing for Brexit hate crime spike against EU citizens and migrants in March

Police are bracing for a fresh spike in hate crime when Britain leaves the EU in March.

Officers fear a repeat of the wave of xenophobic attacks around the 2016 Brexit referendum, which saw numerous physical and verbal assaults on European citizens, including a student who was stabbed in the neck for speaking Polish.

Superintendent Waheed Khan, the Metropolitan Police’s deputy lead for hate crime, said officers would be carrying out proactive work with community groups and awareness campaigns in an attempt to deter potential offenders.

“After what happened with the EU referendum we would expect some kind of response in March, whatever the outcome of Brexit,” he told journalists.

“We will do what we can to provide support to community groups, and make sure people know that hate crime will be reported and it will be acted on.”

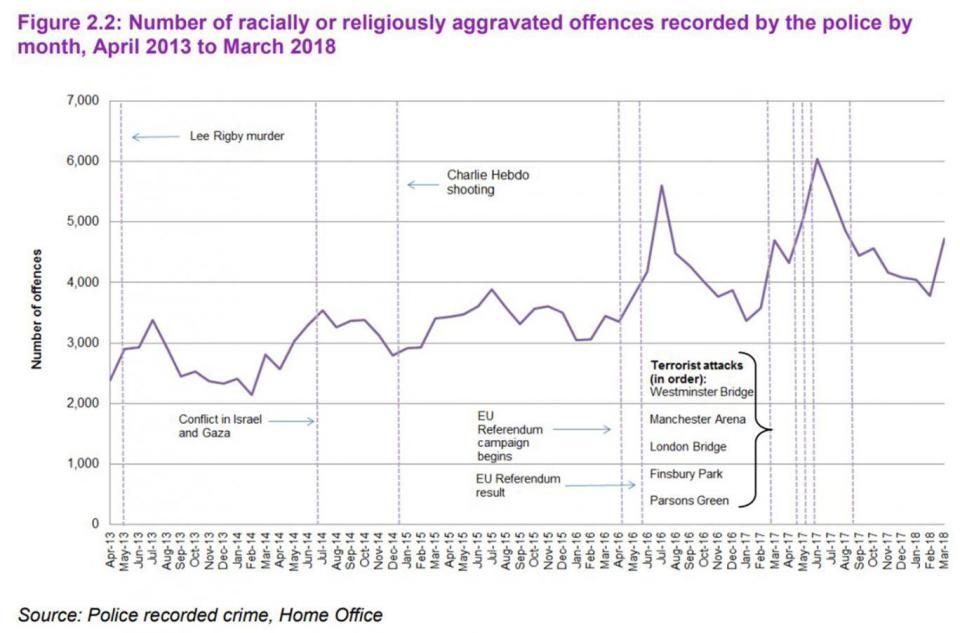

The EU referendum was the biggest spike in hate crime on record in England and Wales, and was surpassed only in the wake of last year’s terror attacks.

“Anecdotal evidence suggests that there was an increase in these types of offences around the time of the EU referendum,” the Home Office said. “Around this time there was a clear spike in hate crime.”

Maike Bohn, a founding member of EU citizens’ group the3million, said it had received reports of hate crime and wider discrimination.

“Some of it is very subtle and some of it is people being yelled at on a bus,” she told The Independent last year.

“I would never compare what’s happening to fellow EU citizens to what’s happening to other minorities – they are the main victims.

“But what is clear to me that during the referendum and afterwards everything has been lumped together – refugees, Muslims, people who are ‘not us coming here’.

“That’s been the rhetoric of Vote Leave and the current government has allowed this to happen.”

A damning report released last year accused the government of fuelling “toxic” anti-immigrant sentiment just as it emerged that ministers have for years vastly overestimated the number of foreign students staying in Britain.

The inquiry from a cross-party group of politicians said Theresa May’s discredited target of cutting net migration to under 100,000 was particularly to blame for “stoking anxiety” that has accompanied unprecedented hate crime following the Brexit vote.

Calling on fellow politicians to tone down their language, the group warned that rhetoric used during the EU referendum led some people to feel “they could act on racist attitudes which had previously gone unexpressed”.

The phenomenon has increased yet further in 2017-18, with religiously-motivated offences rocketing by 40 per cent, transgender by 32 per cent, disability by 30 per cent, sexual orientation by 27 per cent, and race 14 per cent.

Police and monitoring groups believe that social media is also fuelling the crimes, while the statistical increase is also being driven by improved reporting and recording practices.

Phil Adlem, of LGBT+ anti-violence charity Galop, said the algorithms used by web giants can trap people in extremist echo chambers.

“If it knows you like something it sends more stuff your way and that has a snowball effect on hate,” he said.

Dr Dave Rich, head of policy for Jewish charity the Community Security Trust, said: “Social media gives people the confidence to be incredibly rude and aggressive on the street, in a way I think people become desensitised to it because they see it happening so much online.”

Louise Holder, of disability equality group Inclusion London, added: “The concern we have is the links between ordinary people and groups stirring them up.

“There has always been hate crime, there have always been people who don’t like people who look different. But social media creating an atmosphere where people might have thought something but wouldn’t do anything about it, and now they will.”

Hate crime is not an offence in itself, but is used to describe other crimes “motivated by hostility or prejudice towards someone based on a personal characteristic”, such as attacks and vandalism.

Violence against the person, public order offences, criminal damage and arson made up 96 per cent of hate crime-flagged offences. There were 1,065 online hate crimes in the year.

Nationality or xenophobia is not a specific category for data collection but guidance released by the College of Policing said crimes driven by a victim’s perceived national or ethnic origin should be recorded as race hate, as should attacks targeting asylum seekers and refugees.

The overall conviction rate for hate crimes has increased to 84.7 per cent, but only a small proportion of reported incidents – 12 per cent – end with someone being charged or summonsed to court.

The government has announced a wide-ranging review of hate crime laws, which will consider whether to add new “protected characteristics” including age and gender.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News