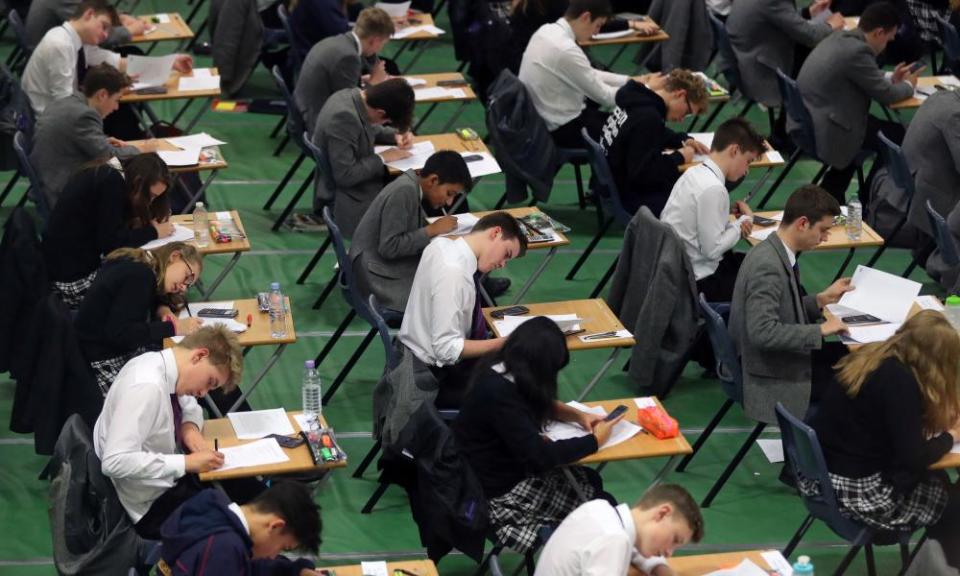

Poorer pupils twice as likely to fail key GCSEs

Disadvantaged pupils are almost twice as likely to fail GCSE maths as their wealthier classmates, according to research that lays bare the attainment gap between rich and poor.

Published on the eve of GCSE results day, the analysis shows students from poorer backgrounds in England lagging far behind their wealthier peers in key subjects at GCSE, prompting calls for the government to put more investment into schools serving deprived communities.

Russell Hobby, the chief executive of the education charity Teach First, which carried out the research, said: “A child’s postcode should never determine how well they do at school, yet today we’ve found huge disparities based on just that. Low attainment at GCSE is a real cause for concern as it can shut doors to future success and holds young people back from meeting their aspirations.”

Two in five pupils (38%) from the poorest one-third of postcodes fail GCSE maths, nearly twice as many as those from the richest third (20%), according to the analysis.

Children from deprived backgrounds are also less likely to be awarded top grades. Just 13% of the poorest pupils attain either a 7, 8 or 9 – the top three grades under the reformed GCSEs – in maths, compared with 26% of their more advantaged peers.

In English it is 11%, compared with 22% of wealthy students, and in French 15% of poorer pupils get top grades, compared with 27% of those from the most advantaged backgrounds.

In geography, 50% of disadvantaged children fail to get a level 4 – a standard pass – compared with 27% of the richest pupils.

Related: GCSE reforms fail to boost A-level English and maths

As with maths, 38% of the poorest pupils fail to pass GCSE English, compared with 22% of the richest. Almost half (46%) of the poorest pupils fail history, compared with 27% of the wealthiest, while 16% of the poorest get the top grades, compared with 31% of the richest.

The findings, based on the government’s underlying key stage 4 results data for 2018, also show that 41% of young people from the poorest communities fail to pass French, compared with 26% of their wealthier peers.

Similarly, pupils from wealthier backgrounds are almost twice as likely to get top grades, with 27% of them getting either a 7,8 or 9, compared with 15% of the poorest.

Last month a study suggested progress in closing the GCSE attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their wealthier classmates had come to a standstill or even gone into reverse.

The study by the Education Policy Institute found that the gap, which had been gradually closing since 2011, widened slightly last year, with the most disadvantaged pupils now almost two years behind their peers by the time they finish their GCSEs.

Hobbysaid promised new government funding for schools should be targeted at areas of greatest need. He also called for higher starting salaries for teachers to boost recruitment.

“We know that it is possible to alter the outcome for children in every area, because time and time again we’ve seen the transformational difference a brilliant education can make, helping all young people to thrive. But if we are to achieve this everywhere, the prime minister needs to not only hold true to his promise of more investment for schools, but he must target it at those in areas of the greatest need,” he said.

The shadow education secretary, Angela Rayner, said the government had embedded inequality in schools, with the most disadvantaged students losing out. “The Conservatives have slashed funding for schools and created a crisis in teacher recruitment and retention, and a generation of children are paying the price for this government’s failure,” she said.

The Department for Education said the gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers had narrowed considerably since 2011 and disadvantaged pupils were already being supported by £2.4bn in additional pupil premium funding.

A spokesperson said: “The prime minister has committed to increasing school funding so we can level up all parts of the UK and close the opportunity gap. We will continue to drive up school standards right across the country and do more to continue to attract and retain talented individuals in our classrooms, as well as giving teachers the powers they need to deal with bad behaviour and bullying.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News