Brexit to make UK more vulnerable to interference from China, report warns

Economic uncertainties after Brexit could make the UK more vulnerable to Chinese interference, with Beijing using a variety of means to infiltrate Britain’s power structures, a leading think-tank has warned.

There has been little focus in Britain on how China preys on targeted countries and there is a need for a cohesive programme to counter it, according to a report by the Royal United Services Institute, which charts the tactics used by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to achieve its aims.

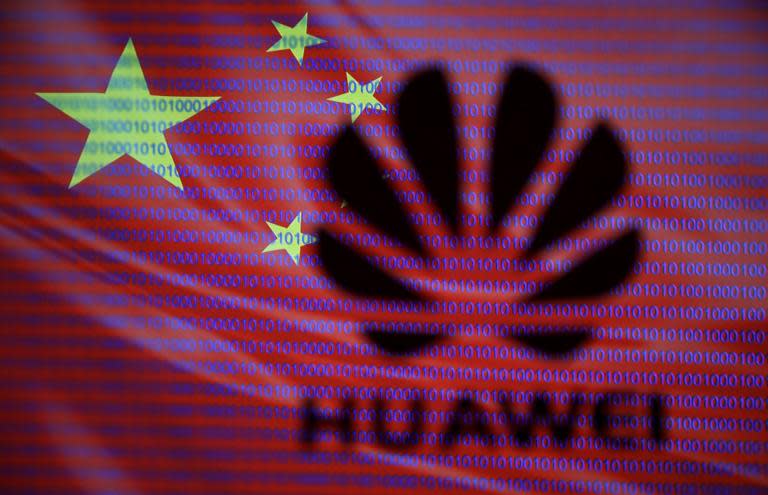

The report examines the “concerted strategy” allegedly used by Beijing, ranging from spreading surreptitious technological reach through mega-corporations like Huawei, to the “elite capture” of people in important positions and opinion-formers by the placing of “advisers”.

Most western European states have resisted Beijing’s efforts to join China’s “Belt and Road” scheme which has been used, say critics, to spread economic and political hegemony in parts of Asia and Africa.

But the UK, seeking post-Brexit trade, has agreed to join the controversial initiative with David Cameron leading a $1bn private fund, supported by the British government.

Last year, 27 of the 28 EU-member-state ambassadors in Beijing (Hungary being the exception) signed off a report saying the Belt and Road project “runs counter to the European Union’s agenda for liberalising trade and pushes the balance of power in favour of subsidised Chinese companies”.

The British ambassador was one of the signatories. But Philip Hammond, on a subsequent visit to Beijing, declared: “I was privileged earlier this year to represent the UK at the first Belt and Road forum and one of the things we will discuss is the opportunity for closer collaboration in delivering the ambitions of the Belt and Road programme.”

The Royal United Services Institute (Rusi) report – “UK Vulnerable to Chinese Influence and Interference Operations” – calls for scrutiny of the “risk of financial dependencies being set up through consultancies offered to retired politicians, who the CCP hopes will push a sympathetic narrative.

“The case of former British prime minister David Cameron, who is involved in a large China fund which aims to invest $1bn in BRI projects, has gained some attention.

“The question of ‘elite capture’ by the CCP has not been closely examined. It should be, including the issue of how much time should elapse between government service and working for Chinese state or quasistate organisations.”

There is no suggestion in the report that the Chinese have tried to influence Mr Cameron.

The Rusi document, compiled by Charles Parton, a former diplomat, states: “The UK’s departure from the EU may increase the Chinese Communist Party’s desire to interfere, as it seeks to implement further a divide-and-rule strategy, aimed at imposing its global vision and promoting its interests”.

The report calls for the development of “systems to prevent non-transparent financing of political activities and lobbying by CCP-backed individuals and organisations; the ultimate donor should be clear, even when monies are channelled through British citizens.”

There are differences, on the whole, between the types of interference by the Kremlin and Beijing, according to the report.

“Except in the sphere of espionage and cyberattacks, CCP interference is not of the Russian kind, which is more deliberately hostile, even destructive. It is more subtle, incremental and often under the radar, although it is occasionally brazen.”

The main goal, it is held, is to promote a “ruthless advancement of China’s interests and values at the expense of those of the west, including through actions which encourage self-censorship and self-limiting policies”.

It points, as an example, to universities and research centres where “junior academics often self-censor to avoid having access to research opportunities withdrawn. Chinese interference in academic freedom also extends to putting pressure on academics, born in China and working in the UK to support the CCP line”.

There must be great caution, the report maintains, in allowing Chinese participation in the UK’s critical national infrastructure.

CCP interference is not of the Russian kind, which is more deliberately hostile, even destructive. It is more subtle, incremental and often under the radar, although it is occasionally brazen

Rusi report

“Were there to be a decision in favour of allowing Chinese operator Huawei to offer fifth-generation mobile networks [5G] in the country it would be ‘at best naïve, at worst irresponsible. This is not least because [Chinese] national security laws require Huawei’s Chinese staff to accede to requests from government departments.”

The search for an optimistic post-Brexit future must not blind the UK to the risks involved, the report cautions. “The UK needs to realise that behind the enticing, but essentially meaningless, language of ‘win-win’ or ‘shared future for mankind’ lies a ruthless CCP agenda to advance its and China’s interests.”

“The UK will not change that, but its aim must be to channel it into a genuinely balanced relationship. In achieving that, language is important: if there must be talk of ‘the Golden Era’ (and within China, the phrase does help UK interests), the UK should not allow it to cloud its perceptions. The UK’s goal must be genuine reciprocity and an equal, mature and comprehensive relationship.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News