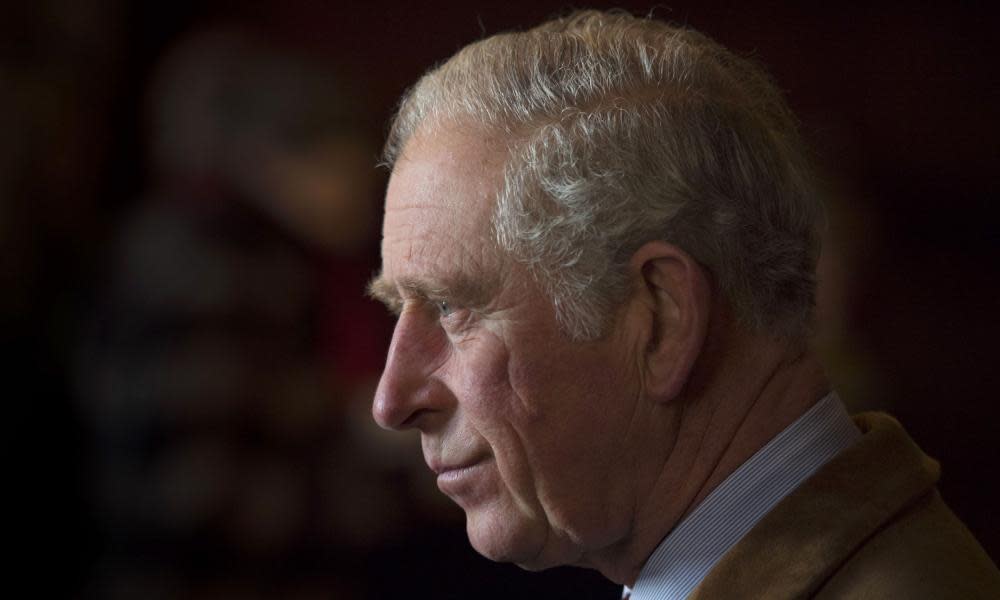

Prince Charles ascension 'could trigger debate on disestablishment'

Prince Charles’s ascension to the throne could trigger a national debate about the relationship between the Church of England and the state, providing a “opportune moment” to make the case for disestablishment, according to the National Secular Society.

Debate about whether an established, privileged “state church” is appropriate in an increasingly multi-faith and secular society is seen by many as off limits while the Queen remains monarch.

But a report to be published on Monday by the society says Charles’s coronation is likely to throw up pressing questions about the institutional links between church, monarchy and parliament.

The report, called Separating Church and State: The Case for Disestablishment, points out that only 25% of countries had a state religion in 2011 and, of those, a minority were classed as liberal democracies.

Only two countries in the world – Britain and Iran – have religious leaders in their legislatures by right. Twenty-six C of E bishops – around a quarter of the total – have reserved seats in the House of Lords, with the right to debate and vote on changes to the law.

The church has a key role in the coronation of a monarch, who is crowned and anointed by the archbishop of Canterbury in an Anglican ceremony at Westminster Abbey.

As well as being head of state, the reigning monarch is head of the church, holding the titles of supreme governor of the Church of England and defender of the faith.

“The wording of the coronation oath, which implies that anyone not sharing the beliefs promulgated at the service are not to be included as full citizens of the state, does little, for an event that is supposed to unite the nation, to suggest any kind of inclusivity,” the report says.

It acknowledges Prince Charles’s reported wish to assume the title defender of faith, rather than “the faith”. The traditional title “will be antagonistic for the non-Anglican majority of the UK population. On the other hand, attempting to avoid this difficulty by adopting the title ‘defender of faith’ will antagonise many supporters of the Church of England,” says the report.

Among other facets of an established church are the formal appointment by the monarch of bishops and archbishops; the formal approval by parliament and the requirement of royal assent to changes to church law; the saying of Anglican prayers at the opening of daily business in both houses of parliament; and the requirement on the C of E to conduct a “national mission”, ministering to the whole of the English population.

The report tackles the principle arguments in favour of an established church: tradition, morality and inclusivity.

“The claim that the Church of England offers a unique source of moral guidance clashes sharply with the regressive stance taken by church leaders on a range of moral issues, and establishment allows them a privileged position in parliament through which they can try to impose these views on others,” it says, citing gender rights, same sex marriage and assisted suicide. “It is simply absurd to imagine that religious leaders have access to a wellspring of ethical knowledge that is somehow denied to non-religious citizens.”

It adds: “The notion that a state religion is required to uphold a sense of national cohesion is clearly anachronistic in a multi- and non-faith democratic society, and it is simply impossible for the church to speak for, let alone actively represent, the multiplicity of faiths and beliefs in modern Britain today (especially since the largest single belief group is now the non-religious). Establishment, by definition, grants undue privileges to one particular religion, to one particular section of the population and to one particular institution.”

The report says overt support for establishment “remains weak” while acknowledging that there is “no clamour” for disestablishment among politicians and that most members of the public are “simply indifferent to the issue”.

But, it notes, the church in Wales and Ireland has already been disestablished and a number of countries throughout the world in the 20th century chose to no longer have a state religion. Norway divested itself of an established church last January.

One way forward could be a “a process of gradual dismantling rather than securing a single clean break”, although even partial steps would face opposition.

The report concludes: “The voices of religious privilege are loud and their vested interests are strong. But if the problems of the 21st century life are to be effectively addressed, and if Britain is to become a modern state rather than one in which parliament continues to cleave to its medieval past, then the separation of church and state needs to be part of the solution.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News