Private sector in the NHS – growing but unlikely to take over

The Labour Party has tried throughout the general election campaign to steer attention towards the NHS. Polls show that Labour is strong on the NHS. It presents itself as the guardian of a free-at-the-point-of-use, publicly delivered healthcare system. Whereas it claims the Conservative Party is bent on privatisation.

This debate is often dominated by sentiment. But what are the facts about the role of the private sector in providing services paid for by the NHS budget?

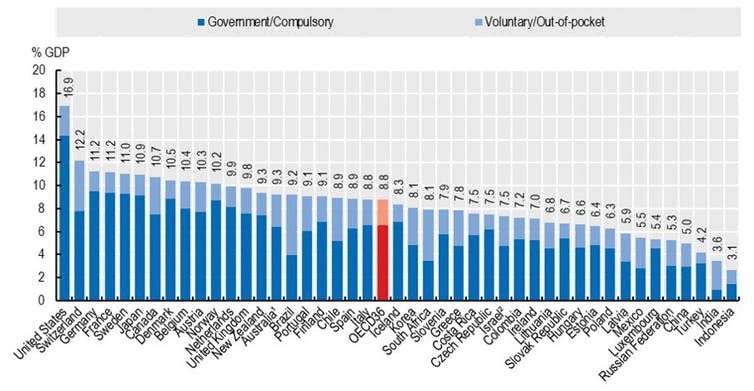

The UK spends more than the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average on healthcare, but less than other OECD countries. In 2018, the UK spent the equivalent of 9.8% of GDP on healthcare – above the OECD average of 8.8%, but less than Germany (12.2%), France (11.2%) and Canada (10.7%).

Following trends in other OECD countries, the amount of money spent per person on private health insurance in the UK increased from US$93 in 2010 to US$122 in 2017. One of the lowest among similar OECD countries.

In return for this spending, the UK has one of the best-performing healthcare systems in the world. According to a set of measures compiled by the Commonwealth Fund, a private US foundation, the UK ranked first out of 11 similar countries in 2016 (although this might have changed in the past few years).

But while the UK is top for care and equity (poor people get the same care as rich people) and third on both access (affordability and timeliness of care) and administrative efficiency, it ranks only tenth on healthcare outcomes.

Reforms to improve efficiency

Spending on the NHS was equivalent to 2% of GDP at its inception, 5% by the end of the 1970s and nearly 10% today. Concerned by the rising cost of healthcare, successive governments over the past four decades have pursued reforms to increase efficiency, accountability and quality of care by stimulating the involvement of the private sector in providing NHS services.

These reforms include the National Health Services & Community Act of 1990, which promoted competition (the so-called “internal market”) to contain costs and improve quality. New Labour kept the “internal market” and sought to incentivise performance through schemes such as Payment by Results. But perhaps the most important reform was the Health and Social Care Act of 2012, which introduced clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) as local purchasers of health services and specified that care be considered from “any qualified provider”. This subtle shift in language opened the door to greater private-sector involvement in delivering healthcare.

Private sector involvement

According to the annual report of the Department of Health and Social Care, £9.18 billion was spent on buying healthcare from independent sector providers by the NHS in England in 2018-19. That’s 7.3% of healthcare spending, up from 6.1% in 2013-14.

Including local authorities and the voluntary sector, 11% of healthcare spending in 2018-19 was on non-NHS providers, up from 8.9% in 2013-14. Others have argued that these numbers downplay the role of the private sector and the true figure could be much higher.

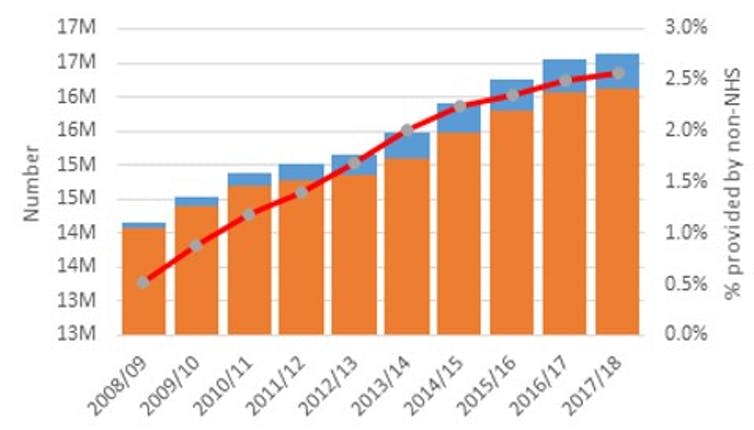

On many measures, the role of the private sector in delivering care in the NHS has grown but remains small. For instance, the proportion of hospital admissions covered by non-NHS providers and paid for by NHS budget increased from 0.5% to 2.5% between 2008-09 to 2017-18.

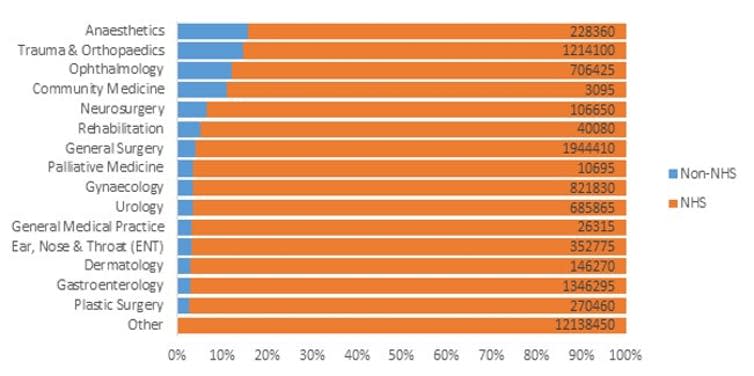

However, the private sector has a far greater role in some areas of care. Looking at admissions by specialty, the largest presence in 2017-18 was in anaesthetics, trauma and orthopaedics, ophthalmology and community medicine.

Greater integration

Significant pressure on the NHS resulted in the commitment in 2018 of an extra £20.5 billion a year to support a new long-term plan. The NHS long-term plan commits to population health management to better prevent and manage disease and greater service integration to contain costs and improve care.

Where the emphasis on competition through the “internal market” may have fragmented services, the new service models envisioned under the long-term plan require greater collaboration.

The first step was the introduction of sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs). STPs cover a larger area than CCGs and were created to bring local health and care leaders together to plan around the long-term needs of local communities. Further models under consideration – including integrated care partnerships, integrated care systems and accountable care organisations – all involve different parts of the health and social care system working more closely together to provide better, more joined-up care.

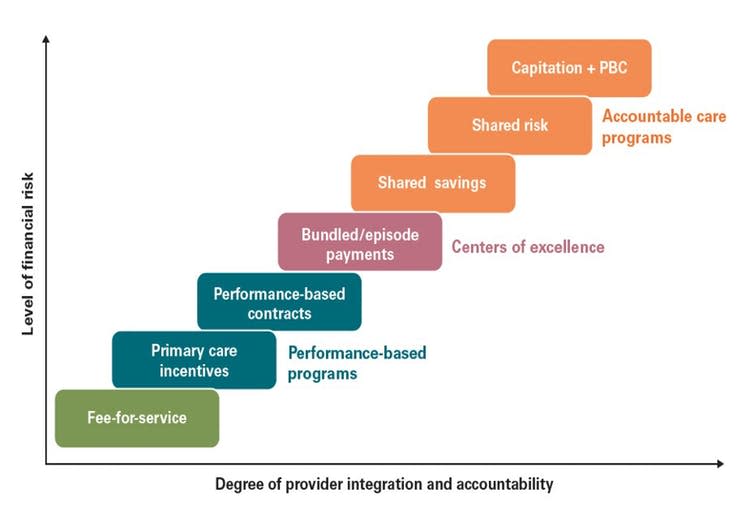

But integrated care brings greater financial risk. The traditional fee-for-service model used to reimburse single organisations for a service provided – paying for a clearly defined activity – is low risk. By contrast a population-based global payment, such as for an accountable care program, means accepting responsibility for the underlying health of a group of patients without it being specified how care should be delivered. This involves more uncertainty and therefore more risk.

So far there has been little expression of interest from the private sector to take the lead on such large contracts, which are generally considered to favour NHS bodies. Recent experience casts doubt over the private sector’s capacity to deliver a comprehensive service in an area as complex as healthcare. It is also not clear that such contracts would be profitable.

Limited, for now

Looking ahead, wholesale privatisation does not seem consistent with the aims and challenges of the NHS. To make this viable, regulation would have to change dramatically to allow large private companies to get hold of the data and service provision for large parts of the population. Instead, non-NHS providers will probably continue to play a limited role in areas where they offer distinctive expertise or efficiencies.

Maintaining and improving the quality of the NHS in a time of rising demand requires increased spending on cost-effective technologies and services. That, rather than privatisation, remains the real dilemma for politicians and the public ahead of this election and beyond.

Correction. The following lines: “Following trends in other OECD countries, the amount of money spent per person on private health insurance in the UK increased from US$1,567 in 2000 to US$4,245 in 2017. This was the lowest among high-income OECD countries.” were changed to: “Following trends in other OECD countries, the amount of money spent per person on private health insurance in the UK increased from US$93 in 2010 to US$122 in 2017. One of the lowest among similar OECD countries.”

And the following sentence: “According to a set of measures compiled by the Commonwealth Fund, a private US foundation, the UK ranks first out of 11 similar countries.”

was changed to: “According to a set of measures compiled by the Commonwealth Fund, a private US foundation, the UK ranked first out of 11 similar countries in 2016 (although this might have changed in the past few years).”

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Apostolos Tsiachristas receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research through the Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and the Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley .

Stephen Rocks does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News