Pupils dressed as slaves? It says a lot about our approach to black history | Lola Okolosie

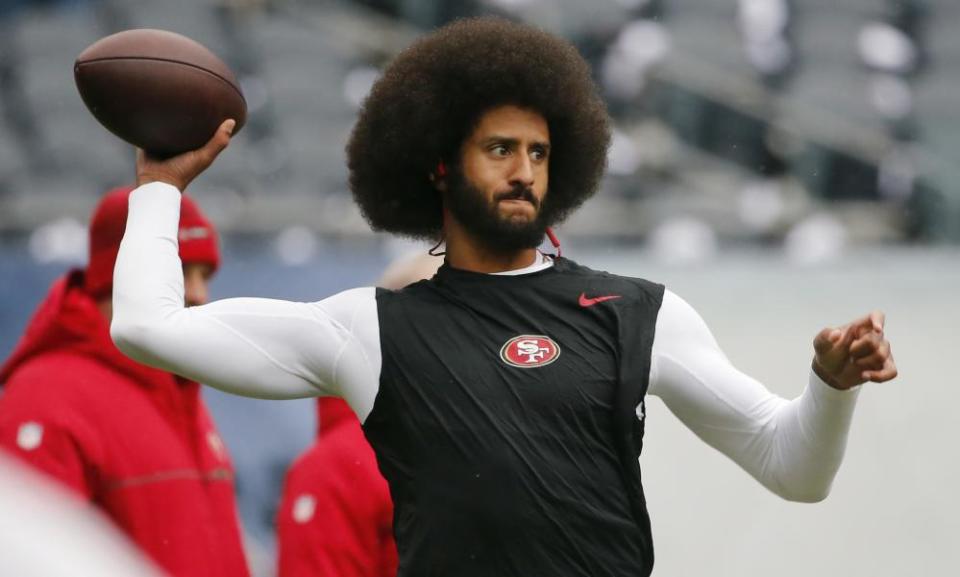

If you’re a teacher wanting to mark Black History Month with a discussion of racism, what is the best way to go about it? A helpful start might be to look no further than the treatment of NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick or 102-cap former England player Eni Aluko.

Each October, here in the UK at least, Black History Month will mean that some schools, believing the inherent issues too sensitive to broach, will forgo mention of it altogether. Sadly, this will include schools where students are predominantly black. Still there will be others, both diverse and monocultural, where a celebration of this history will mean dusting off old displays about Martin Luther King and Mary Seacole. There will be a recognition that racism, a plague that has robbed us all of a richer understanding of black history, is a bad thing.

Perhaps in a bid to soothe worried young minds, all of this will be presented as an evil that happened long ago until people such as Rosa Parks refused to be treated as second class citizens. And the present, 2017, will appear as the realisation of the equality black people once dreamed of. End of story.

Except, of course, report after report tells us what we as black and minority ethnic people already know: that racism flourishes in our midst.

This is perhaps a better starting point into a discussion about racism for primary school children than the one attempted by a teacher in the London Borough of Newham last week. Possibly well meaning and definitely tactless, letters were sent home asking parents of a particular class to send their children to school dressed as slaves. All so that they could appear as singing – and most probably happy – slaves. Over 20% of Newham’s residents are black.

In a bid at verisimilitude, the letter requested that children “performing their Black History Month song” should not do so wearing “modern patterns or modern brand names” but instead appear in “dirty and worn out” clothing. Parents were kindly told that “it might be an idea not to wash these clothes and stain them with tea or coffee to look more authentic”. A helpful tip if ever there was one.

Incidents such as this will continue to occur, glitches in a system that persists in seeing black history as no more – minus the Egyptians – than the conquest of white Europeans over Africans.

It is a history, if done correctly, that should encompass teaching about African civilisations such as the Ife kingdom of Nigeria or Aksum in present day Eritrea, which existed and flourished well before European conquest. And it should include at least a few mentions of the varied resistance taken before the civil rights movement. As a young girl, I would have loved to have learned of the Amazons of Dahomey, an all-female military regiment who in 1890 started fighting French encroachment into present-day Benin.

We can teach our young people about black history, and make it something more than a history of passivity and victimhood. At the same time, we should see it as our responsibility, as their educators, to teach them that the legacies of those darker days remain with us today. Not all racists have shaved heads and an NF membership card, or pepper their speech with a liberal dose of the N- or P-word. Such honesty is necessary. If not, how else can their generation stand a fighting chance of discussing race in ways that are far more sophisticated than adults currently seem capable of?

• Lola Okolosie is an English teacher and award-winning columnist focusing on race, politics, education and feminism.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News