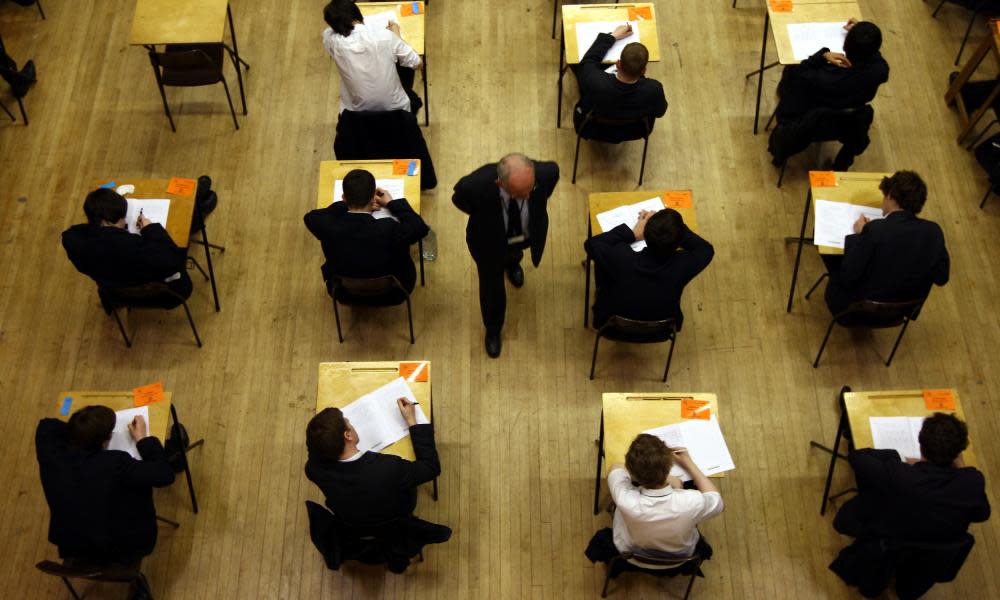

Pupils in England likely to face reduced GCSE courses and delayed exams

Pupils in England who are due to sit their GCSEs next summer will be taught a reduced curriculum in a small number of subjects and will have their exams delayed by a few weeks, under new proposals drawn up by the exams regulator, Ofqual.

The changes have been drawn up to try to mitigate the impact of learning time lost due to school closures during the Covid-19 pandemic, which has meant that students will not have enough time to cover the entire curriculum.

However, headteachers said the measures failed to address the scale of the learning loss and called for an urgent “plan B” in case of continuing major disruption due to the coronavirus made it impossible to hold a full exam series next year.

Ofqual has asked exam boards to draw up plans for GCSE exams to start after the summer half term next year – moving the exam series back from May to a starting date of 7 June 2021, running into July – in order to allow more teaching time. This could delay results.

Delaying A-levels is also under consideration but this may be more complicated because of the pressure to deliver results promptly so students can secure places in further and higher education.

“We are also seeking views on whether such a change would be appropriate for the AS/A-level exam timetable, and the impact of any delay in issuing results,” Ofqual said.

Epidemics of infectious diseases behave in different ways but the 1918 influenza pandemic that killed more than 50 million people is regarded as a key example of a pandemic that occurred in multiple waves, with the latter more severe than the first. It has been replicated – albeit more mildly – in subsequent flu pandemics.

How and why multiple-wave outbreaks occur, and how subsequent waves of infection can be prevented, has become a staple of epidemiological modelling studies and pandemic preparation, which have looked at everything from social behaviour and health policy to vaccination and the buildup of community immunity, also known as herd immunity.

Is there evidence of coronavirus coming back in a second wave?

This is being watched very carefully. Without a vaccine, and with no widespread immunity to the new disease, one alarm is being sounded by the experience of Singapore, which has seen a sudden resurgence in infections despite being lauded for its early handling of the outbreak.

Although Singapore instituted a strong contact tracing system for its general population, the disease re-emerged in cramped dormitory accommodation used by thousands of foreign workers with inadequate hygiene facilities and shared canteens.

Singapore’s experience, although very specific, has demonstrated the ability of the disease to come back strongly in places where people are in close proximity and its ability to exploit any weakness in public health regimes set up to counter it.

In June 2020, Beijing suffered from a new cluster of coronavirus cases which caused authorities to re-implement restrictions that China had previously been able to lift. In the UK, the city of Leicester was unable to come out of lockdown because of the development of a new spike of coronavirus cases.

What are experts worried about?

Conventional wisdom among scientists suggests second waves of resistant infections occur after the capacity for treatment and isolation becomes exhausted. In this case the concern is that the social and political consensus supporting lockdowns is being overtaken by public frustration and the urgent need to reopen economies.

The threat declines when susceptibility of the population to the disease falls below a certain threshold or when widespread vaccination becomes available.

In general terms the ratio of susceptible and immune individuals in a population at the end of one wave determines the potential magnitude of a subsequent wave. The worry is that with a vaccine still many months away, and the real rate of infection only being guessed at, populations worldwide remain highly vulnerable to both resurgence and subsequent waves.

The regulator has also drawn up proposals to reduce the amount taught in some subjects including GCSE history and geography, with more optional questions in some exams, so teachers have the freedom to choose topics to concentrate on, rather than being required to teach the entire curriculum.

GCSE English, maths and science are seen as essential, however, and will be unchanged, and – under the current plans – there are no proposals to reduce what’s taught at A and AS-level in any subject.

Ofqual is consulting on a number of other adaptations to give teachers more time to cover content and help relieve pressure on students. These include plans to allow GCSE students to observe practical science work rather than undertake it themselves and the removal of the compulsory computer programming project.

Though pupils will generally face the same number of exams in each subject and exams are expected to be the same length, GCSE and A-level art and design students will be assessed on their portfolio alone and will not be required to complete a supervised task. In GCSE geography, fieldwork will not be assessed.

Related: English schools to open full time in September with few restrictions

Ofqual’s chief regulator, Sally Collier, said: “We have considered a wide range of options before coming forward with a set of proposals for next year’s GCSE, AS and A-level exams, which will help reduce the pressure on students and teachers, while allowing them to progress with valid qualifications which higher educational institutions and employers can trust.”

Geoff Barton, the general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, responded: “These plans appear to amount to little more than tinkering at the edges of next year’s exams, despite the massive disruption to learning caused by the coronavirus emergency.

“We understand that it is difficult to scale back exams in a way that is fair to all pupils, but we fear the very minor changes in this consultation fail to recognise the enormous pressure on schools and their pupils to cover the large amount of content in these courses.”

A consultation on Ofqual’s proposals is now under way and the regulator will announce its final decision on next year’s exams in August.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News