What it’s really like to live in Rwanda

On Tuesday, Prince Charles flew into Kigali, ahead of this week’s Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting. Boris Johnson, who is heading proceedings, is expected to join him in the Rwandan capital today as will Justin Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister.

I lived and worked in Kigali for five years as a journalist, but was refused accreditation to report on the event. My crime? Being critical of the Rwandan government. Paul Kagame, Rwanda’s president, is using this elite gathering – where Kigali will doubtless be presented at its best, polished to perfection – to burnish his international image and conceal his dictatorship. Make no mistake: Rwanda’s human rights crimes are being whitewashed by events like these.

To arrive in Kigali is to confront a facade of modernity and progress. There are no beggars on the streets, though the country is among the poorest on Earth. The electricity in Kigali rarely cuts out. The government touts its gender-equal parliament — making it one of the few countries in the world to have achieved such parity (although parliament has almost no power, and largely rubber-stamps Kagame’s directives). Living in Kigali, it can be easy to believe the government’s claims that it is a beacon for Africa.

This is no doubt part of the reason that the UK has struck an astonishing deal to deport asylum seekers in the UK, many of whom are fleeing dictatorships, to Rwanda, a dictatorship. After a century of narratives portraying Africa as backward, a successful African country invites hope. Rwanda, we are being told, has moved on since the horrific days of the 1994 genocide when over a million citizens, many of them ethnic Tutsi, were brutally slaughtered. The current gathering of international movers and shakers in Kigali only embellishes this story.

Kagame is a crafty player in this game. A skilled rhetorician, his high-minded speeches call upon a deeply-ingrained sense of humiliation and historical injustice in his population, while claiming to craft a new nation proud of their history – and serve to conceal his near-totalitarian state.

While living in Rwanda, I taught a class of Rwandan newspaper journalists in a media program financed by the European Union. When I first arrived, I too was seduced by Rwanda’s facade: Kigali’s restaurants, its efficient public services and clean, safe and well-lit streets. The weather was cool almost all year round, and the hills around Kigali, long like baguettes, made a beautiful skyline. Rwanda is incredibly safe – unless you anger the government, in which case it quickly becomes extremely unsafe. Over the years, I witnessed my students and colleagues shot dead, imprisoned and forced to flee the country after they criticised Kagame. Sometimes their criticisms were benign, or made in obscure newspapers; but Kagame is intolerant.

I wrote a book entitled Bad News: Last Journalists in a Dictatorship, telling these brave Rwandans’ stories, as well as mine, as I tried to keep them safe. More than 70 Rwandan journalists who were killed, disappeared or fled are listed in the appendix. I did not list all the academics, activists, soldiers, politicians, priests and teachers who met the same fate.

The names of the brave reporters I taught are taboo, and cannot be spoken of without risks to their safety. Kagame has declared many of them enemies of the state. In Rwanda, such simple acts as taking notes or gathering in groups to discuss politics are transformed into possible acts of treason. Punishments vary from assassinations to imprisonment, or more insidious events, such as bank loans suddenly needing repayment in full.

Prior to the 2010 presidential election, which Kagame won with 93 per cent of the vote (he won the subsequent 2017 election with nearly 99 per cent of the vote), I was reporting at one of his election rallies. A police officer stepped up to me and told me he had observed me look at Kagame and write. “Looking and writing,” he said. “That’s not allowed.” I shut my notebook and for the rest of the rally, wrote on the palm of my left hand, which I closed into a fist as I left the rally grounds.

The president is, through his security agents, all-seeing. He decides which stories can be told. All of Rwanda, every inch of the country, is divided into “villages”, comprising about 100 families each, which report to and receive orders from the president’s office with great efficiency. In 1994, this decades-old system, which pre-dated colonial rule by the Belgians, was used to perpetrate the genocide, which began almost simultaneously across the country and killed with a speed even greater than the Nazis achieved in the Second World War. Kagame has kept this dangerous system intact.

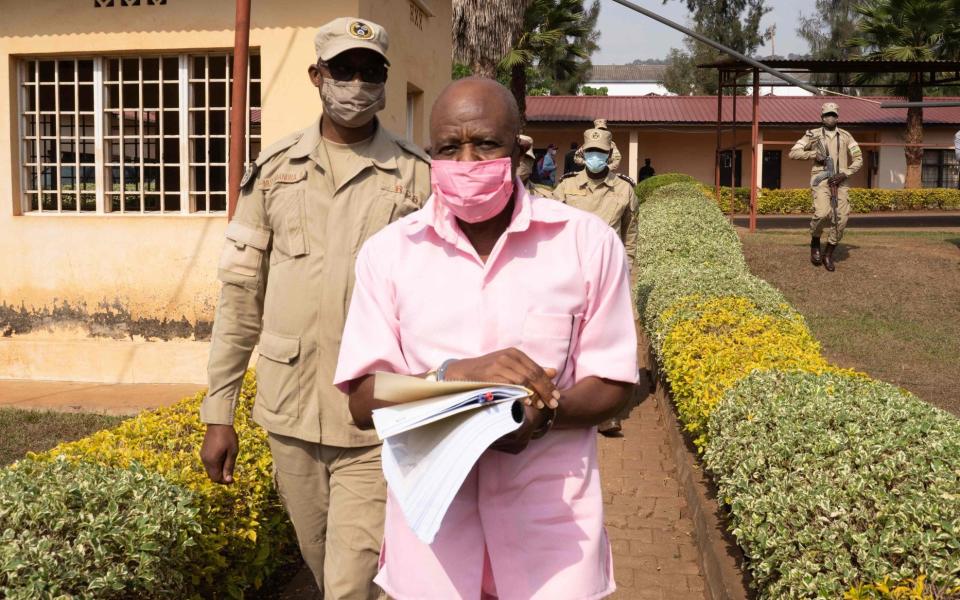

High-profile critics of Kagame are subjected to Rwanda’s sham courts, which are virtually powerless and part of the façade. International justice organisations, such as the Clooney Foundation, recently reported on the trial of the ex-Hotel Rwanda manager Paul Rusesabagina, who had been living in exile in the United States. Rusesabagina, on whose life the Hollywood blockbuster Hotel Rwanda was based, was kidnapped in Dubai two years ago, brought to Kigali against his will, and now languishes in a prison with little hope of release, his popularity a threat to Kagame.

Rusesabagina’s daughter, Carina Kanimba, speaks to him every weekend for five minutes. At the Oslo Freedom Forum last month, she told me, “My father’s lip hangs limp. His arm is in pain, and hanging at an unnatural angle, indicating a loss of control.” Kanimba, whom Rusesabagina rescued from a refugee camp during the genocide and adopted, says Rwanda has denied her father access to an independent doctor, and that a Rwandan doctor has diagnosed her father’s ailments as “psychological”.

The Rwandan government regularly issues blanket denials to human rights reports documenting its abuses. The government says it is a democracy, and that its society is free.

But Rwanda’s human rights crimes are being whitewashed by international sports and political events. This year Kigali hosted the Basketball Africa League, and this week Kagame will receive the leaders of Commonwealth nations, including Prince Charles and Boris Johnson. Kagame will use the Commonwealth gathering to further burnish his image. Foreign leaders will be presented with Kigali’s facade, with little reason to look at the dictatorship behind it.

While living in Kigali, I once happened to be on the terrace of a building, and noticed a hole in the walls. I went up to look. To my surprise, I saw the president’s office. From the street, one could only see high walls and gates.

It was within that presidential compound that decisions were made about who would go to prison and who would be free, who would die and who would live. So I was surprised to see this office from above so clearly.

I could see the buildings neatly laid out and manicured lawns. A voice came from behind: “What are you looking at?” It was a security guard. He told me, in a gentle voice, I wasn’t allowed to look through that hole. The guard asked why I was looking at the president’s office. His calmness unnerved me. I told him that I looked for no particular reason; and immediately I felt guilty. I wondered if I should keep looking or turn away. The act of looking had been turned into something insidious. I wondered about the things I had seen and written about – many of which the government would not have wished to be known. I wondered if I had been observed all along. Often, I felt safe only in the confines of my office.

When my journalism students were attacked, I was forced to look behind Kagame’s facade, to understand why it was so dangerous to speak up against his powerful government, financed and trained in security matters by Western countries including the US, Israel and the UK. I discovered a sophisticated, controlling dictatorship, and power so concentrated in Kagame that to challenge him – even peacefully – is to risk exile, imprisonment and even death. The world might be marvelling at Rwanda right now. The UK might tout the country as a humane solution to its refugee crisis. But don’t be deceived – for all its beauty Rwanda is, in reality, a prison like any other.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News