We remember Citizen Smith fondly but is there a place for him in today's politics?

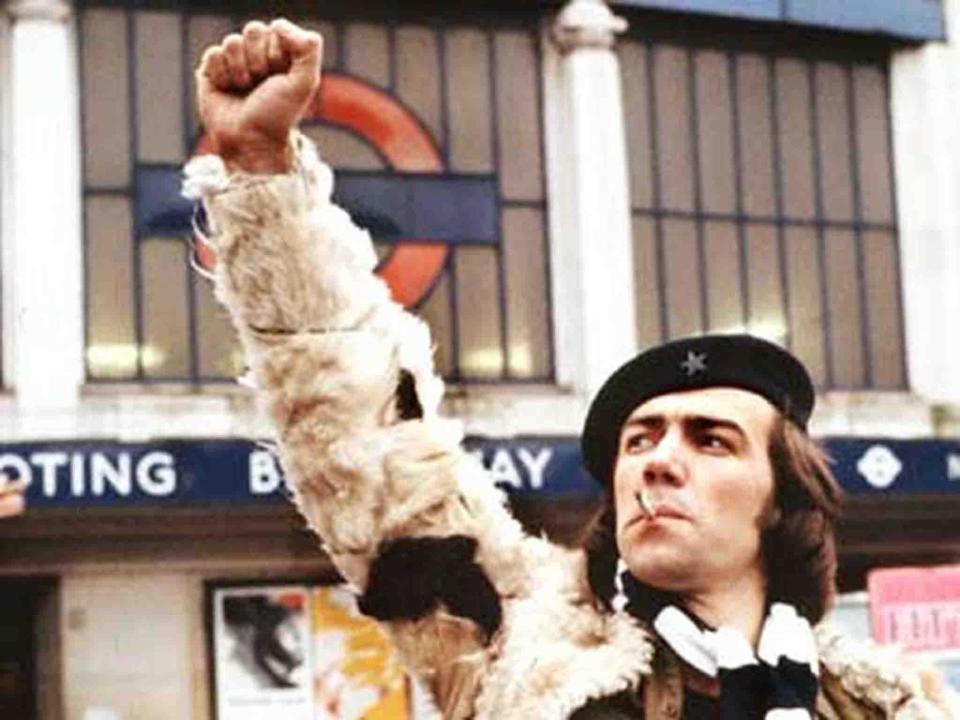

A young man steps out of Tooting Broadway tube station. He has long hair, and a beret, a guitar slung over his shoulder. Someone, somewhere, is whistling the socialist anthem The Red Flag. He liberates a bottle of pale ale from a dray truck and as the music swells to a crescendo he stops, breathes deeply, and issues a mighty cry. Power to the people. An old lady stops and stares at him.

It could, conceivably, be a scene from modern London, a bright, young Corbynista on his way to a Momentum meeting, his thoughts on how the New Left can topple the dominant elite that holds the wealth and power in a mid-Brexit kingdom rapidly heading towards being disunited.

But of course it isn’t. It’s a scene from your telly just about 40 years ago, when BBC1 (in the days of just three channels!) aired the pilot episode of a brand new sitcom, Citizen Smith.

TV hadn't seen the like of Citizen Smith before, and nothing’s touched it since — that’s evident from the number of people who remember it so fondly. It was a curious beast that walked a tightrope of comedy and politics thanks to the deft touch of screenwriter John Sullivan, who quite frankly pulled off something of a coup with the presentation of his subject matter.

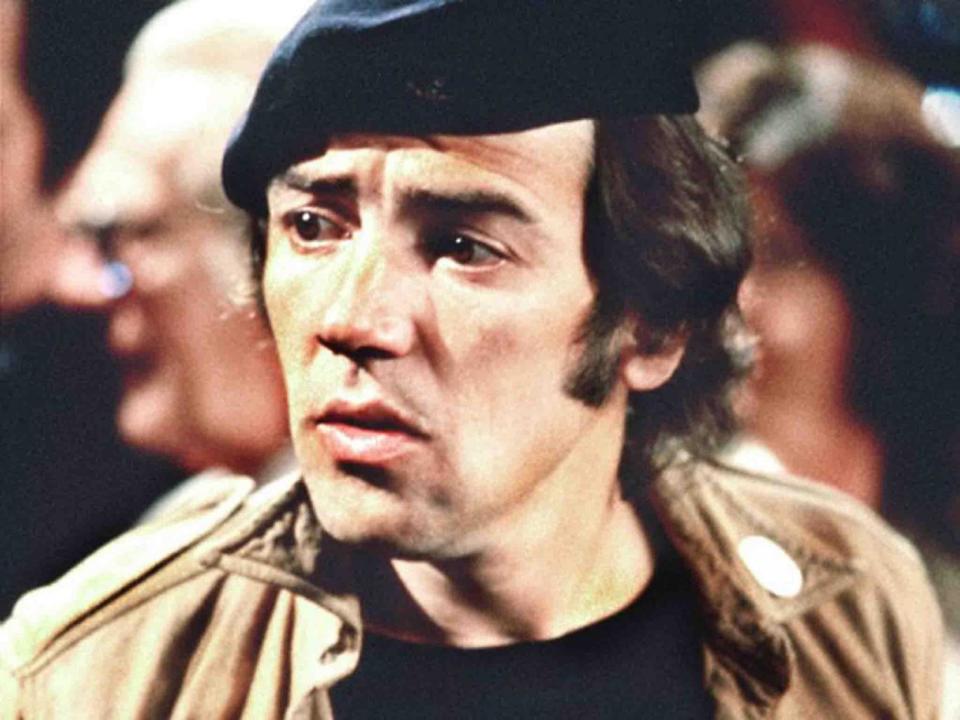

The politics was the whole point, but Wolfie Smith’s pantomime Che Guevara turn was, on the one hand, to be laughed at rather than fully sympathised with. On the other, he was surrounded by reactionary, entrenched bigots, and this was Sullivan’s masterstroke, to appeal to both demographics in the same show. You could sit in front of the TV and cheer on Wolfie against the mainstream of then older generation, while your parents on the sofa beside you would shake their heads at his anti-social revolutionary tactics.

Wolfie, or Walter Henry Smith (that’s right, WH Smith) was played to a tee by Robert Lindsay, who had already made his name in a clutch of British films and in the RAF National Service sitcom Get Some In! He is idealistic to the point of delusion, the nominal leader of the Tooting Popular Front, a small group of misfits mainly comprising Wolfie’s long-suffering pals Ken (Mike Grady) and Tucker (Tony Millan). Wolfie’s girlfriend Shirley (played in the first two series by Lindsay’s then real-life wife Cheryl Hall) refuses to be politicised and just wants to settle down, spurred on by her down-the-line parents, portrayed wonderfully by Peter Vaughan, who died last year, as Cheryl’s constantly angry father, and Hilda Braid as her mother, who always refers to Wolfie as “Foxy”.

Citizen Smith was Sullivan’s big break in TV. He would later go on to achieve lasting fame as the creator of Only Fools and Horses and Just Good Friends. But in the early 1970s he was working at the BBC’s props department, where he finally got to push his script for Citizen Smith into the hands of a decision maker, and on 12 April 1977, the pilot was screened as a one-off Comedy Special on BBC1. The first series began proper in November and it ran for four years.

“Sullivan was from a working-class background and although he never professed to be a Marxist, to even pitch a sitcom based on a revolutionary Trotskyist suggested some affinity for revolution, or kicking against the system,” says TV scriptwriter, critic and broadcaster Andrew Collins. “Neither antagonist was let off the hook — Dad’s reactionary kitchen-table conservatism made him look foolish, especially when undercut by his politically neutral wife, and Wolfie’s idealism was also depicted as foolish. In the same way that Esmonde and Larbey treated the woolly eco-warriors and the middle-class snobs with affection in The Good Life, I think Sullivan found something to like in both extremes: Dad’s decency and Wolfie’s passion.”

Looking back, perhaps the success of Citizen Smith might have made more sense had it been launched at a time when there was a Conservative government for Wolfie to rail against. But 1977, of course, was in the tenure of Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan. However, it was a nuanced, divisive time when Labour was having to cut deals with other parties to maintain its hold with a Commons minority, inflation was in double figures, meaning deflationary public spending cuts were being put into place, and unemployment was rising. The Winter of Discontent, in which the trade unions railed against Labour’s pay restraint policies, was brewing, and the way would shortly be paved for the triumphant entry into Number 10 of Margaret Thatcher.

So Sullivan’s idealistic left-winger Wolfie was not a mere comedy confection, he was a product of his time. And nobody else was using the medium of the sitcom to reflect the political and social landscape in this way. Citizen Smith was one of the few comedies of the day that really focused on the day-to-day lives of the working classes. Look at what else was around in 1977: the middle-class mores of Abigail’s Party, the gentle nursing home comedy of You’re Only Young Twice, the teeth-clenching “lets all laugh at Johnny Foreigner” Mind Your Language.

Citizen Smith was really of its time in the way it distilled wider politics and events through the comedic interaction of the characters. And not only that, it was educational. Collins says, “I was watching it, avidly, as a boy aged between 12 and 15, living in Northampton, so I would’ve been forgiven for having a pretty weak handle on the politics of the show, and its key south London location. As a student in the Eighties, I moved to London and lived very near to Tooting, but it may as well have been a fictional place when I enjoyed the sitcom at home with my parents.

“Crucially, I grasped the key antagonism of the show between the lodger, Wolfie, and his girlfriend’s dad, although I wouldn’t have been able to tell you who was left- or right-wing. As a kid, I sided with Wolfie, as he was youthful and idealistic, and that was clearly the intention of John Sullivan.

“I learned the names Che Guevara, Chairman Mao and Trotsky from Citizen Smith. You have to start somewhere. It’s the same way I learned about philosophers, from a Monty Python sketch.”

That was the genius of Sullivan. He wrapped up his extremely shrewd observations in jokes about mothers-in-law and being too skint to take your girlfriend out for a meal. He was also extremely prescient. Take Wolfie’s monologue from the first scene of the pilot episode:

“One day, citizen, there’s going to be a revolution in this country. And they will recall that it was I, Wolfie Smith, who led the people on that glorious day. Can you imagine, Ken, all the oppressed masses taking to the streets in one festival of the people? Snotty-nosed kids dancing a ragamuffin dance of freedom. Plumbers with machine guns. Black blokes with hand grenades. Rabbis with flak jackets. And afterwards, everyone will be left in peace.”

Stirring stuff, defused only by Wolfie, who is daubing the words JOIN THE REVOLUTION – THINK AHEAD on a brick wall as he speaks running out of space and blaming the Tory council for making “small walls”. Then, four years later, that sort of uprising was exactly what was happening in Brixton and Toxteth, but the riots did not quite usher in the utopian dream of Wolfie Smith.

So why do we still love Wolfie? Because revolution is timeless? Because even the most politicised of us needs to sometimes take a step back and look in the mirror? Journalist Grace Dent says, “I think that it shows the quality of the writing that Citizen Smith is still a jokey, friendly insult I hurl about today. Citizen Smith nails the painfully, unintentionally hilarious way our friends behave whenever they become fully politicised. Especially on the left. One of my good friends right now has begun a market in Ealing and harps on endlessly about Ealing and its microclimate and how it’s the greatest place in London. Just yesterday I said: ‘You are like Citizen Smith’.”

She cites her fellow Independent writer and comedian Mark Steel on the subject and adds: “The more left you become, the more you loathe other lefties for not being quite left enough. Until you literally are the Tooting Popular Front.”

Sullivan tapped into that and it’s just as relevant today. “Lindsay nails that idea of sexy, youthful, laughable idealism,” says Dent. “I think the observation is probably as strong as Orwell's The Road to Wigan Pier. I had to re-read this recently and was gobsmacked at how little things have changed regarding the middle classes and the working classes adopting Corbyn’s views.”

Ah, yes, Jeremy Corbyn. It’s almost impossible to see the Labour leader ducking under the foliage in his front garden and trotting down Islington’s streets in his little cap and not think of Wolfie. In 1977 Corbyn was a councillor in Haringey, at the age of 27. Surely he must have watched Citizen Smith? I put in a request for an interview to his office; sadly they haven’t come back yet.

Like in 1977, the Labour party is somewhat in disarray, though for very different reasons. Is it time for another show like Citizen Smith? Indeed, what’s Wolfie doing now? In this very newspaper in 2015 Robert Lindsay said: “I’ve been chased by a production company which is very much trying to get Wolfie to run for the Labour Party and bring him back into power. I think that’s a fantastic idea.”

Despite John Sullivan dying in 2011, Lindsay hinted: “There are moves afoot in the industry to bring Citizen Smith back with some respected figures that I very much admire.”

However, it was not to be. Sullivan’s son Jim told the BBC a couple of days later it was “not something we would want to do”. He said: “Every episode of Citizen Smith was written by my Dad – all the lines, ideas and plots were his. As we have said about Only Fools and Horses, the show only ever had one writer and it is going to stay that way.”

Which, perhaps, is a good thing, says Andrew Collins. “The trouble with today’s domestic politics is that the right and the left are no longer polar opposites — Blair and Cameron saw to that. When Corbyn is running a three-line whip, without a trace of irony, to get his MPs to vote with the Conservative government on Article 50, what’s the point of writing a sitcom about the left?

“I’d love to think people are arguing about politics over the breakfast table like Wolfie and Charlie did in Citizen Smith, but I rather suspect they’re not. We have a US President who is beyond parody and a UK Government which thinks 51 per cent is the will of the people.”

Plus, he adds, the world’s turned several times since Wolfie’s day. “When Wolfie, Ken, Tucker and the Tooting Popular Front stole a tank and hid it in the garage, only to accidentally shoot some garden gnomes with a machine gun, it was presented as a farcical story line,” Collins recalls. “That wouldn’t play in a world where terrorism haunts our every waking moment and extremists drive lorries into innocent bystanders. Better to make a sitcom about marriage, or kids, or sharing a flat, which is what everybody is doing.”

Which is true, but also not a huge amount of fun. Wolfie Smith would probably be about as old as Jeremy Corbyn (Lindsay is also 67) and though his return to our screens is unlikely, I still like to think of him emerging from Tooting Broadway station, sticking his fist in the air, and letting rip with a “Power to the people!”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News