Remember this about Donald Trump. He knows the depths of American bigotry | Gary Younge

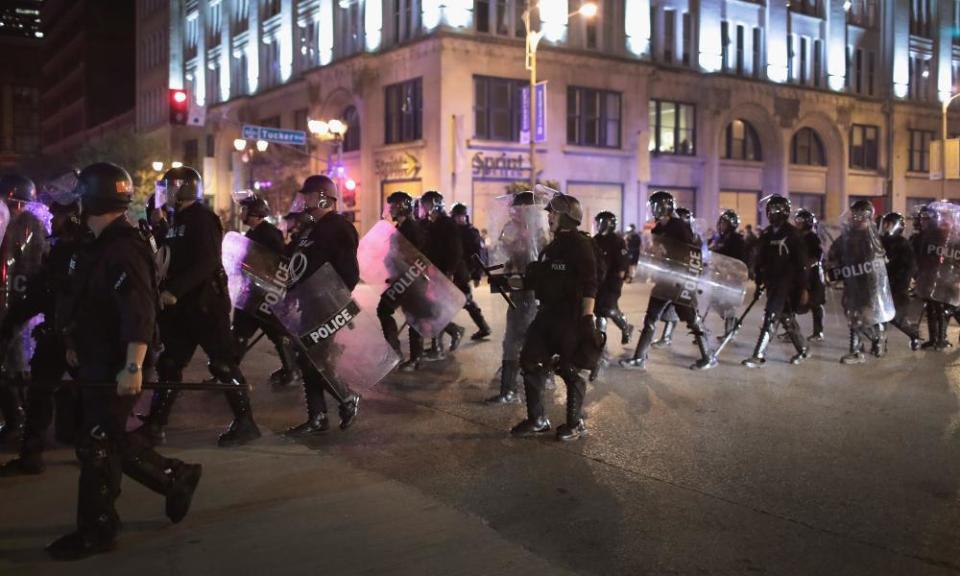

Two Sundays ago, after a night of tense confrontations, police in St Louis trooped through the city chanting: “Whose streets? Our streets.” They were mocking marchers protesting at the acquittal of a former police officer, who had fatally shot a black man after a high-speed pursuit. This in the city just a few miles away from Ferguson, where Michael Brown was shot dead in the middle of the day in 2014.

Then last Friday, Donald Trump went to Alabama and branded NFL players who have been expressing their support for Black Lives Matter by kneeling during the pre-game national anthem, “sons of bitches”. To cheers from the crowd, he said: “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. He is fired. He’s fired! … Total disrespect of our heritage, a total disrespect of everything that we stand for. Everything that we stand for.” This in the state that kept its local ban on interracial marriage until 2000.

The battle lines in America’s struggle against racism and white supremacy are become increasingly clear to a degree not seen since the 60s. With the balm of Barack Obama’s presence in the White House having so quickly evaporated, the contradictions of the post-civil rights era are once again laid bare. The codified obstacles to freedom and equality have been removed, but the legacy of those obstacles and the system that produced them remains. Black Americans are far more likely than white people to be stopped, frisked, arrested, jailed, shot and executed by the state, while the racial gaps in unemployment are the same as 40 years ago, the racial disparity in wealth and income is worse than 50 years ago. They have the right to eat in any restaurant they wish; the trouble is, many can’t afford what’s on the menu.

“The Negro today finds himself stymied by obstacles of far greater magnitude than the legal barriers he was attacking before,” wrote the civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, presciently, in 1965. “Problems which, while conditioned by Jim Crow, do not vanish upon its demise. They are deeply rooted in our socio-economic order.”

So on one side of these battle lines, alongside elders of the struggle, a generation of young activists kneels in rebellion against that “socio-economic order”. Informed by a decade or more of activism ranging from Black Lives Matter to Occupy Wall Street, they have been schooled in resistance against war, austerity, police shootings, homophobia, immigration and a range of other issues.

This is the generation that produced Colin Kaepernick, the young black San Francisco 49ers quarterback who caused a sensation last year by refusing to stand for the national anthem: “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour,” he said. “There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.” He would continue until “[the American flag] represents what it’s supposed to represent”. Others soon followed suit.

In 2012 I asked John Carlos, one of the US Olympians who raised his fist in a black power salute in Mexico in 1968, if he saw any prospect of political resistance emerging again through sport. “Today, if an athlete doesn’t have a view of their history before them, then they have a view of just that big cheque in front of them,” he told me. “It’s not the responsibility of the oppressor to educate us. We have to educate ourselves and our own.” Clearly there has been a lot more education going on than anyone realised. Kaepernick’s protest had been brewing for a while. Since the killing of Brown in 2014, a number of black athletes had been wearing protest T-shirts related to police shootings. Kaepernick took it to the next level by pitting the reality of American racism against the mythology of American patriotism.

This was a high-stakes move. Football is a multibillion-dollar business. No one ever got rich leading a popular protest against racism. (Indeed, Kaepernick was let go by the 49ers for this season). And no one ever went broke betting on the popular appeal of American racism either.

For on the other side of the divide stand the defenders of white supremacy, resentful at eight years of a black president and bewildered by the broader geo-political decline that has seen lost wars, lost trade and stagnant wages. With white America set to become a minority within a generation, they are desperate not only to protect privilege but to contort history. Defending everything from the statues of confederate generals to the right of police to shoot unarmed African Americans, they have found an advocate in the White House.

Sooner or later we are going to have to stop being shocked by the racial obscenity of this presidency. As a candidate, Trump stood as an unvarnished racist, a shameless xenophobe – he has been as good as his word. When he stokes racial enmity he is merely fulfilling the promise of his campaign. The bigotry he expresses is not new. What is new is that it should have found such a brazen voice in so high an office. In the past couple of months he has equivocated on condemning neo-Nazis, called some of those who marched with neo-Nazis “fine people” and encouraged the police to rough up suspects.

Racism in American politics used to rely on clear symbols and plausible deniability. “You have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the blacks,” Nixon once told his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman. “The key is to devise a system that recognises that while not appearing to.” Now it seems appearances don’t matter. It’s not a dog whistle when everyone can hear it. It’s just a straight up whistle.

But if the battle lines are clear, the outcome of this particular battle remains in doubt. America was 200 years a slave state; 100 years an apartheid state; and just over 50 years a non-racial democracy. The concept of equality is relatively new.

Not everyone got the memo. Trump knows his base. Those who knelt were booed in some stadiums. While white Americans overwhelmingly oppose the idea of white supremacy, its core message still holds considerable appeal: almost half of white Americans believe “white America is under attack” and a third think “America should protect and preserve its white European heritage”.

That said, after Trump’s tirade many more NFL players knelt this weekend. Other teams refused to come out for the anthem. A range of entertainers and other sportspeople have joined in. Coaches, owners and the NFL itself slammed Trump for his comments. It remains to be seen if that coalition will hold. But for now it is growing in size and confidence. That, in itself, is cause for hope.

• Gary Younge is a Guardian columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News