Remembering Chic bassist Bernard Edwards, the other half of Nile Rodgers' musical brain

This summer looks set to be a big one for Nile Rodgers.

The 66-year-old guitarist will be seen at at least five UK festivals this summer, as well as curating the Southbank Centre’s prestigious Meltdown festival in August — David Byrne, Yoko Ono and Robert Smith are among the previous incumbents.

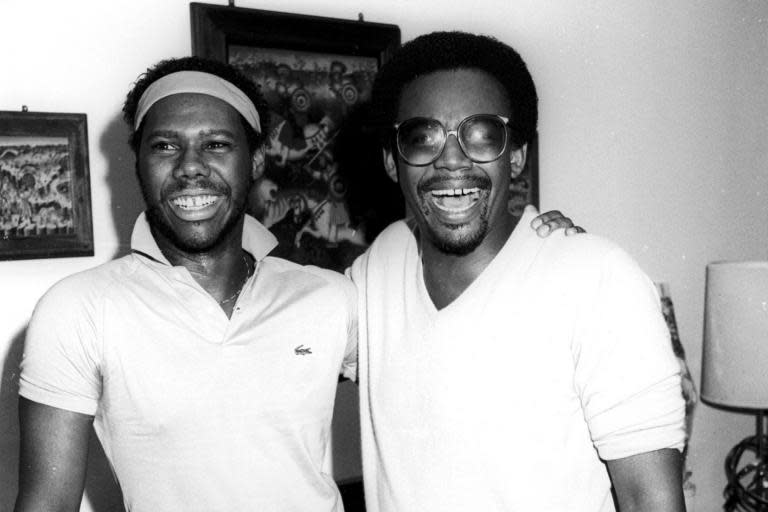

Rodgers has been full-steam-ahead since 2013, when Daft Punk injected a healthy dose of rocket fuel into his resurgent career by asking him to co-write their best-selling single Get Lucky. It introduced the ground-breaking artist, and his band Chic, to a new generation of music fans and reshone a light on his groundbreaking career. But there was a man who this fresh legion of admirers might not have been aware of: Bernard Edwards, the other half of Rodgers’ musical brain.

He was the private, pragmatic and preternaturally talented bassist whose beguilingly simple grooves helped to turn Chic into a world-conquering band by the end of the 70s, in the process crafting what has become the "Nile Rodgers' sound".

Rodgers and Edwards met in 1970. The former was a fledgling musician, cutting his teeth in the house band of Harlem’s Apollo Theatre – and, bizarrely, the Sesame Street band – while the latter was a promising young bassist who held down a menial job at the local post office to provide for his young family. One night, they played together at a club in the Bronx and on the train home afterwards, they realised they had a mutual connection at Edwards’ workplace — Rodgers’ girlfriend’s mother.

They began to play together and, before long, it was obvious they had stumbled upon something singular: an effortless songwriting partnership, fortified by a kindred bond. The pair started playing around New York, performing under various guises — largely, it was as the soul-tinged Big Apple Band, but they cycled through numerous other names and styles, including a stint where they went new wave as Allah and the Knife-Wielding Punks. Finally, they settled upon Chic, and began a career as arguably the greatest disco band of all time.

Talking about their songwriting partnership in the mid-90s, Edwards said: “[Rodgers] used to come up with a lot of really great hooks… so it always worked well together that way. He’s really commercial-minded, and I always tried to keep it solid — a nice foundation.”

In many ways what he said is true — Edwards’ ever-dependable playing allowed Rodgers to douse each of the tracks in his trademark vibrancy — but it’s also a huge understatement. Edwards’ riffs were more than just foundational, they were utterly fundamental. He played with unwavering precision, crafting timeless bass lines that became just as recognisable as the melodies and vocal hooks that glided over them.

A prime example is on the 1979 track Good Times, in which the bass line doesn’t so much walk as elegantly saunter. It was funky and sophisticated — “sophisto-funk”, as Rodgers aptly called it — and elevated the song from a solid slice of disco to an era-defining anthem. It even played an inadvertently seminal role in the formation of hip-hop, after being stolen by the Sugarhill Gang for their game-changing single Rapper’s Delight, widely credited as bringing the genre to a mainstream audience for the first time. After some legal wranglings, Edwards and Rodgers were eventually named as co-writers on the track.

Despite a string of hit singles — Le Freak, Everybody Dance and Dance, Dance, Dance (Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah) chief among them, all with stonking bass lines — released in under two years between 1977 and 1979, Chic eventually fell victim to changing trends. The pair found substantial success as a producing duo, though, working with Sister Sledge and Diana Ross, but by the early 80s, disco was truly out of favour. Both worked with Duran Duran too, the group Rodgers would later call his "second band".

Chic disbanded in 1983 and both Edwards and Rodgers pursued solo producing careers. Edwards’ work was impressive, lending his meticulous hand to albums by Rod Stewart, Debbie Harry and Robert Palmer. Commercially, he was eclipsed by Rodgers, whose production was integral to some of the most important albums of the 80s, with Like A Virgin by Madonna and David Bowie’s Let’s Dance among them.

He couldn’t do it all without Edwards, though.

“When I was working with David on Let’s Dance,” Rodgers recalled years later, “we ran into this one song and for some reason the bass player, who played brilliantly on the rest of the album, couldn’t understand what we were doing. I said to David, because I could feel him getting a little frustrated: ‘Bernard will be in here and out of here in 15 minutes, that’s a promise.’”

Edwards was downstairs in the same building, working in the studio with Diana Ross. He came up and fulfilled that promise.

“Bernard looks at the chart, plays right through it, puts down his bass and says: ‘Is that what y’all want?’ I said: ‘Yeah!’ He picked up his bass, packed up and walked out,” Rodgers recalled.

It was the same level of trust that, in the last gig the pair ever played together in 1996, led Rodgers to believe the short gaps Edwards was leaving in his bass lines were merely improvisations — and not, as it turned out, a symptom of the rare strain of pneumonia that would take the bassist’s life hours later.

That final show took place in Tokyo in April 1996, four years after a revitalised Chic reformed and released an album, Chic-ism. Edwards was showing signs of his ailments before the gig, but insisted it shouldn’t be cancelled. Those pauses in his playing during the gig were a result of him momentarily passing out, before regaining his composure and carrying on. Once the music had stopped and the crowds dispersed, Edwards returned to his room, fell asleep and drifted away. Rodgers found the body later on that night.

“Not only did I feel as if I'd lost my best friend, I felt as if my music was taken away from me – he's half of my music,” Rodgers told the Independent in 2009.

In the years that followed, Rodgers hired new musicians and continued to tour with Chic. The Daft Punk smash, and the huge bookings that followed, were deserved rewards for Rodgers, whose own musical endeavour has rightly marked him out as one of the most influential American artists of all time. That said, he couldn't have got there without Edwards.

“There will never be another Bernard Edwards,” Rodgers said last year. “I have the time of my life playing these amazing songs we created together every day, but I will never be able to replace him and the special chemistry we had.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News