After a repentant Trump voter's one-man protest, what happened next?

Regrets, he’s had a few, but then again, there’s one he’d like to mention.

James Walker voted for Donald Trump in 2016. That fateful decision, and a subsequent act of public of repentance, rippled through his family and friendships, his dating life, his career, where he makes his home and countless thousands of posts on social media.

Related: 'They're not alone': Biden aims to unite anti-Trump Republicans at DNC

Walker’s story is a parable of the times, a glimpse of how the Trump era has awakened ordinary citizens, who might otherwise sit on the sidelines as presidents come and go, and how the internet has become a turbocharged amplifier of division and hatred, healing and redemption.

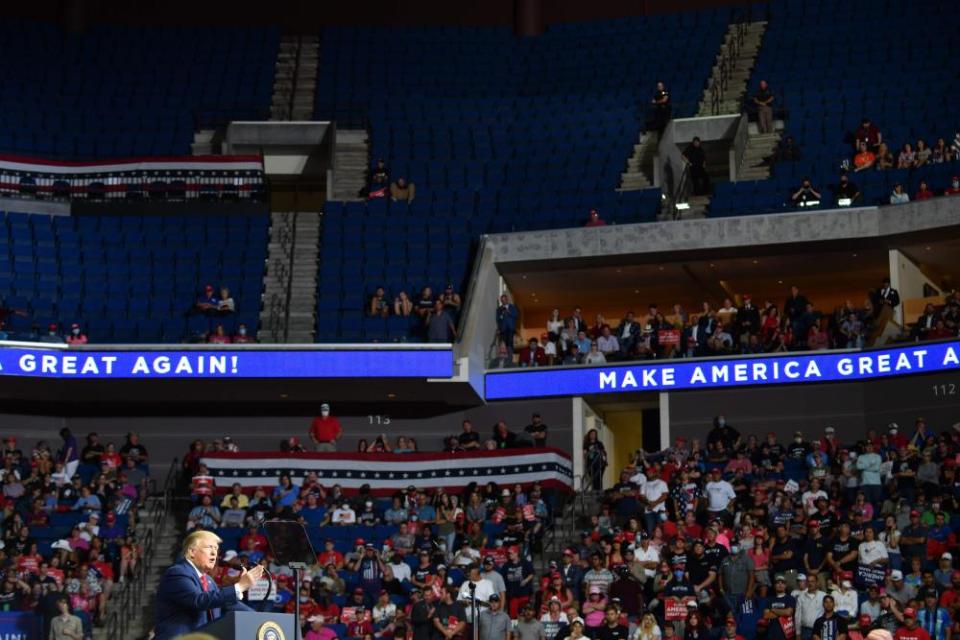

It was March 2017 when Trump, still in the foothills of his presidency, held a rally in Nashville, Tennessee. As usual, there was a small group of protesters outside the venue, the Nashville Municipal Auditorium. Unmissable among them stood Walker wearing beard, sunglasses, black North Face jacket, khaki trousers. Most strikingly, he wore a red “Make America great again” (Maga) cap on his head and a sign in his hands that announced to the world: “I’ve made a huge mistake.”

As a picture it was worth a thousand tweets. It soon went viral on social media, featured on the Guardian and Reddit websites and was cited by the comedian Bill Maher on his HBO show Real Time. A Twitter post from this Guardian reporter that day has now accumulated 42,000 retweets and 82,000 likes. Among the earliest comments: “no worries man. Join the #resistance”; “Wow – James Walker – takes guts to do that – no matter who you voted for. Most people wouldn’t do that.”

I felt frustrated and didn’t know which way to go and then immediately felt like I had made the wrong call

Many wanted to know: why did he vote for Trump? And why did he change his mind? Walker grew up in a conservative family in northern California and spent two years in the military but, by 2016, had begun to question the direction of the Republican party; nevertheless, he plumped for Trump over Hillary Clinton.

“I was mid-transition when that election came up and I felt frustrated with both candidates that were put up and didn’t know which way to go and then immediately felt like I had made the wrong call,” he explained by phone from Los Angeles, where he now lives. “Within a few months I had become so frustrated that I felt it was necessary to stand up and do something.”

Walker, 35, did not own a Maga hat but ordered one when “a random, crazy” idea took hold in his mind. When the president came to town, he put the red cap on and took along his sign expressing repentance. He was “scared” what reaction he might get as thousands of Trump supporters poured into Nashville, he admits, and had two friends standing nearby as “bodyguards”.

“I intended to stand there for like five minutes and get a photo that I could post as my own private protest, but within two minutes you [Guardian reporter] walked up to me and I didn’t even entirely know how to react to that. I thought if someone came up to me, I would probably need to start running for the exit.

“Immediately after that, more people started coming up to me and I ended up staying for hours. I marched all around with the protesters and so many of them came up to me and gave me hugs and thanked me and said me taking a stand like that was inspiring. It really moved people.

“People were crying and it just felt like a really healing moment which was not what I expected. It reinforced my hope that I could find a way to be an activist, even in my own kind of quirky way of standing there in a red hat and holding up a sign as a regretful Trump voter.”

But when Walker approached people attending the Trump rally, the reception was rather less warm. “It felt like there was a lot of toxicity and I didn’t even feel safe over there.”

He went home and assumed that would be the end of it.

But that evening he started getting text messages from friends and family members saying he was going viral on Twitter. “That kind of freaked me out,” he admits. “Most of the responses from people who were sending me screenshots were positive, but my family was not happy and were rather upset with me doing that.

That was the point at which I almost felt like I might have made a mistake because the comments turned very nasty

“They said, ‘Why would you do something to hurt Trump?’ I was surprised by that because I thought, ‘Wow, I can’t believe that I could do something that hurt Trump’, so that was rather exciting but, at the same time, it started a longstanding rift down party lines in the family, which is kind of the thing that the whole protest was about, hoping to break down those walls.”

The morning after his protest, Walker received more text messages telling him he had made it to the front page of Reddit.

“That was the point at which I almost felt like I might have made a mistake because the comments turned very nasty and started to attack every aspect of my character and all these unknowable things. I became a target for a lot of people’s frustration, and that’s when I felt like I need to shut down and just regroup and think through whether or not I would take another interview.

“I only read the comments for a couple hours and I never went back but I remember that they targeted my physical appearance. Of course they attacked me as someone who would admit to voting for Trump and therefore a fool, and then they homed in on other details from the picture like me wearing my military-issue pants, and so they attacked by military service record.”

The reaction among friends in the liberal bastion of East Nashville was mixed. “I had a surprising amount of friends on my side but then there were those who just didn’t understand why I would do something like that. To an extent, I didn’t either. I just felt compelled because it seemed like such a critical moment that, in any way I could, I needed to do something and it seemed to work.”

He recalls: “I started dating someone and she had to tell all of her friends that she was dating the guy who went viral in the Maga hat in Nashville a week or two ago.”

As the weeks went by, Walker remained ambivalent about whether he had done the right thing. “I was unsure whether or not my intent came across, but Bill Maher ran a story on it and said, ‘The world needs more Republicans like this guy,’ and, when I heard that, I felt like my intentions were heard and that was the message I was going for.

“Republicans aren’t all hateful Trump supporters and, even as I’m disappointed in many of them, I see a path to close the divide. But it’s only through healing and communication and both of those seem to be off the table right now.”

In a similar spirit, last week the Democratic national convention featured Republicans including Colin Powell, the former secretary of state, and John Kasich, the ex-governor of Ohio, as well as repentant Trump voters arguing it was time to put country before party. Groups such as the Lincoln Project and Republican Voters Against Trump have attacked what they frame as a cult of personality that threatens the fabric of American democracy.

But Walker found less charity online.

While the internet enabled him to get his message out, it also opened the floodgates to abuse, bullying and trolling, including from liberals and Democrats who refused to forgive his vote. The web has also become a defining feature of American politics: an incubator of both social activism and rancid tribalism.

It just seems like no matter what my intent is, it gets torn apart and there’s no room for conversation

Walker reflects: “This event inspired me to go more public with my activism and my thoughts on issues and every time I do part of me regrets it because I get such a mixed reaction.”

“So I’m trying to figure out how to navigate being something of an activist online and I haven’t cracked the code. It just seems like no matter what happens, no matter what my intent is, it gets torn apart and there’s no room for conversation, which is always my intention: just to start a conversation.”

Walker’s journey to activism led him to quit his job as a wine broker in Nashville and move to Los Angeles, where he has found work in the film industry and hopes to become a documentary maker with an emphasis on social justice and socially conscious projects.

This year he joined Black Lives Matter marches in Los Angeles and posted pictures of them on social media. Again he was out of step with his family. “They didn’t understand or appreciate that I would publicly support Black Lives Matter because they’re more of the All Lives Matter crowd.”

His parents, he believes, remain committed to Trump but, in case anyone is still wondering, he intends to vote for Democrat Joe Biden in November. An act of atonement, perhaps. Whatever the outcome, however, there is little chance that the election will heal America’s cold civil war overnight.

“When I march at protests I feel hopeful but when I come home and turn on the news I feel otherwise,” Walker muses. “It feels like a mix back and forth every day of optimism that change is around the corner and is accessible for us, and then feeling like there’s too much toxicity now.”

“Until we can put aside those dividing issues and realise we’re all Americans and demand change, until those walls break down, I just don’t know how we’re going to come together.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News