‘His reputation will never recover’: the rape trial that took down Harvey Weinstein

Harvey Weinstein’s career in the movie business has risen and fallen as markedly as his famous temper.

Long before he faced harassment and assault charges from scores of women he worked with over the years, and before he was the symbolic villain of the #MeToo movement paying top-dollar to fend off rape charges, Weinstein was busy defending himself from something much more ordinarily Hollywood: the notion he was a gigantic jerk.

Matt Damon once compared him to a scorpion, saying “it’s his nature” to sting people. Meryl Streep, accepting an award for best actress in 2012, thanked, “God, Harvey Weinstein, the punisher, Old Testament, I guess.”

Streep’s metaphor was apt.

At the time he was one of the most powerful men in Hollywood as co-founder of Miramax and the Weinstein Company, and as producer of some of the previous decades’ top movies. He was a kingmaker helping to shape the careers of top directors like Quentin Tarantino and A-listers like Gwyneth Paltrow. He could make careers, and he could break them.

But Pulitzer prize-winning reporting from the New York Times and the New Yorker that exposed decades of sexual harassment and assault allegations against him, and culminated this year in a criminal trial in New York, saw Weinstein become a virtual untouchable – toxic to most of those who formerly feted him with a surname that has become a byword for abuse, not Oscars.

Weinstein is unlikely to ever return to the top. That’s according even to people whose job it is to redeem the reputation of the seemingly irredeemable. “His reputation will never recover,” said Shannon Wilkinson, a New York-based reputation management consultant.

Ken Auletta, an early profiler of Weinstein now at work on a biography of the mogul that is due out in 2021, agreed. “Who’s going to want to act in a Harvey movie? What studio is going to recruit him?”

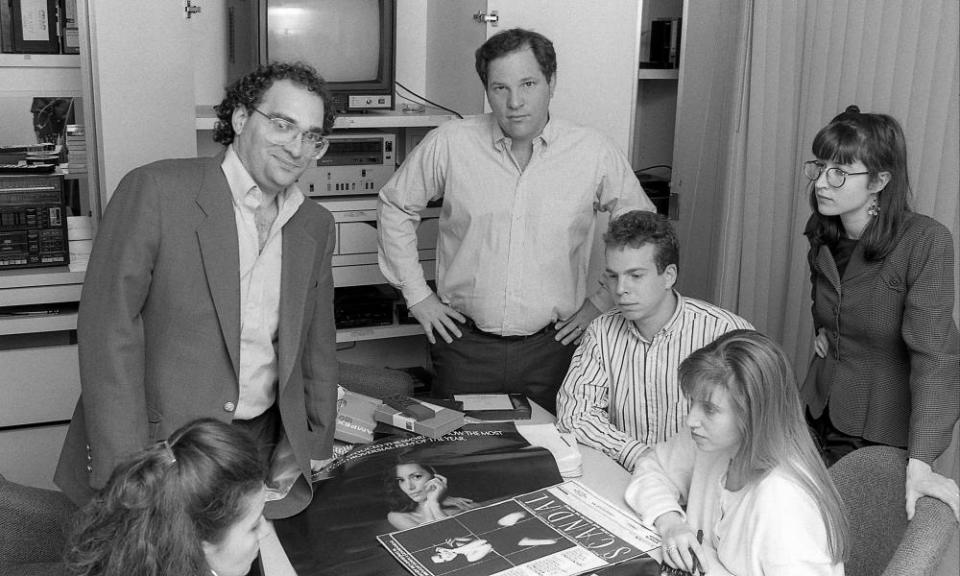

The early years

Weinstein grew up in Queens and from a young age his father Max would take him and his brother Bob to the movies every Saturday. They went to see foreign films, dramas, everything – and though his father would sometimes fall asleep, the boys relished the outings and promptly became cinephiles.

Weinstein took readily to the role of movie historian, incorporating things he learned in his weekend movie sojourns to what he was learning in school. An old classmate, Jeff Malek told the Hollywood Reporter that Weinstein “knew the entire cast of every movie” and that when he tested him with questions about The Wizard of Oz, Weinstein “proceeded to list the cast and crew, including gaffers, wardrobe, etc, by memory”.

Not everything the Weinsteins learned at home was so helpful. In a 2011 tribute piece to his dad, Bob Weinstein recalled how once after his mom received an unflattering haircut at the beauty salon, she demanded her husband seek revenge. “‘Have the hairstylist fired and sue the beauty parlor for everything they’ve got,’” Bob recalled his mother saying in the piece he penned in Vanity Fair.

Bob meant to relay it as a playful anecdote, writing: “Max and his sons learned a valuable lesson that day. No matter what, the hair always looks great.” But looking back at Weinstein’s career, and the long list of claims that he was explosive and abusive to underlings, it’s hard not to wonder if he didn’t have a different takeaway.

Weinstein first started to leverage his bold personality into a career while attending school at the Buffalo branch of the State University of New York, where he founded a concert promotion business, Harvey & Corky Presents, with his friend Corky Burger, and quickly made a name for himself by bringing big names like the Rolling Stones, Frank Sinatra and Bob Dylan up to Buffalo.

By 1973 he had dropped out of school, and was running a local theater where he showed three movies for the price of one on Saturday nights, according to Auletta’s New Yorker profile in 2002.

He and Bob wanted to get into the movie business though, so in 1979 he used the proceeds made from Harvey & Corky Presents to, along with his brother, found Miramax, an independent film distribution and production company named for their parents, Miriam and Max.

“It wasn’t very expensive to do that,” Auletta said. “Distribution was really cheap to do, and they had a good eye and they spotted movies like Sex, Lies and Videotape, which was their first major hit.”

Other successes followed and in June of 1993, Miramax was bought by The Walt Disney Company for $80m in a deal that allowed the brothers to stay on creatively. Director Quentin Tarantino’s cult classic movie Pulp Fiction, which was backed by Miramax, came out a year later and was awarded the Palme d’Or award at the Cannes Film Festival. In 1997, The English Patient landed Miramax its first Academy Award for best picture. And in 1999, Shakespeare in Love won seven Oscars, including a best actress award for Gwyneth Paltrow.

The setback

But even in his heyday, Weinstein was developing a reputation as difficult to work with, even against the high bar of Hollywood where dictatorial directors and arrogant studio heads are the norm.

After a string of successes, he hit a rough patch in 2005. Disney divorced the Weinstein brothers that year following disputes about budget and creative control.

The brothers launched their own independent studio, the Weinstein Company, the same year. But they struggled initially to repeat earlier successes. Films released in the first few years included a number of duds, and rumors about his temper were starting to catch up with him in the insular circles in which he moved.

As early as the 1990s, the New York Times was reporting settlements he had made with various women – among them Rose McGowan in 1997 and numerous assistants.

“It’s a recurring theme with him,” said Auletta, who wrote the groundbreaking New Yorker profile of Weinstein in 2002 highlighting his abusive behavior and hinting at his sexual malfeasance, though Auletta was not able to confirm it with women going on the record at the time. “He apologizes and says, I want to change,” Auletta continued. “He’s done that all through his adult life. But in my experience, he hasn’t changed. He couldn’t control his temper.”

The comeback and the fall

But by 2011, Weinstein was back on top again, as changing audience tastes caught up with his aesthetic. That year The King’s Speech was nominated for a dozen Oscars and awarded best picture. The following year he racked up a pile of Golden Globe awards for films including My Week with Marilyn, Iron Lady, and The Artist – an ode to the golden era of silent films which would go on to win best picture at the Academy Awards.

A spate of glowing profiles portrayed Weinstein as the quintessential “comeback kid” of Hollywood, including one by the New York Times media writer David Carr entitled A Mistake to Write Off the Weinsteins. Another piece in Gawker described him as rising from the grave to “feast on the bones of his enemies”.

Weinstein was back near the height of his powers when he heard that reporters were snooping around allegations of rape and sexual assault that had long been simmering.

In response he used the full breadth of his connections, money and ruthless self-interest, to try to quash them. He hired lawyers, private investigators and even an intelligence firm founded by ex-Israeli spies called Black Cube, which counter-investigated the reporters who were investigating him.

He also leaned on longstanding relationships at NBC News and tapped relationships at other media outlets, including David Pecker, the now notorious head of the National Enquirer who also kept secrets and killed stories for Donald Trump.

But Weinstein couldn’t hold back the tide.

In the fall of 2017, the New York Times and the New Yorker published stories documenting years of alleged abuse and kicking off what would become the #MeToo movement, a worldwide reckoning around sexual harassment and assault by powerful men in countless industries. Weinstein ended up in court, a powerful symbol for women worldwide of powerful men abusing their position for sex.

Civil attorney Ari Wilkenfeld, a partner at the DC-based firm Wilkenfeld, Herendeen & Atkinson, who specializes in discrimination, said Weinstein’s trial has triggered important changes.

For one thing, Wilkenfeld – who has represented female clients in a number of high-profile #MeToo cases, including Brooke Nevils when she accused Matt Lauer of rape and Linda Vester when she accused Tom Brokaw of sexual harassment – has seen a renaissance in people caring about sexual harassment law.

“We’re finally getting somewhere,” he said.

He also noted the Weinstein trial has been important in highlighting the defense’s line of argument that if women had really been raped or assaulted they wouldn’t continue to have any kind of relationship with their abuser.

Wilkenfeld said that’s not the case. “People behave in ways that seem antithetical to members of the jury. They might delay in reporting; they might deny that the rape occurred. They might have a romantic relationship with the person after the assault or rape; they might do any number of things that, to an ordinary person, don’t make sense. And the challenge is to explain the psychology of what a victim and survivor goes through and how there’s no straight line and no one way a person reacts,” he said.

Similar legal defenses were mounted on behalf of rapist college football coach Jerry Sandusky, Wilkenfeld noted, and the prosecution was ultimately able to overcome predictable skepticism.

Sarah Ann Masse, a Weinstein accuser involved in the class-action lawsuit against him, sees justice in Weinstein’s position in the dock.

“I think losing his job and the fact that he’s on criminal trial are exceptionally important,” she said, adding of powerful male abusers that “we have to hold them accountable”.

“I’m hoping what this will do regardless of the outcome is help educate the public about what it’s really like to be a survivor of sexual violence,” she said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News