Rob Brydon and Steve Coogan: 'Work-wise, Steve's terrific. On a personal level, appalling'

It is mid-June in Epidaurus and the temperature is climbing towards 35 degrees. There is a burr of cicada and birdsong, and the mountains are a distant blue beyond a row of cypress trees. At the amphitheatre, regarded as the most acoustically and aesthetically perfect example of a Greek theatre, Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon stand 25 rows up, hands on hips, panamas on heads. For several minutes they bicker and berate one another; they impersonate Laurel and Hardy and Richard Burton; they discuss Pink Floyd, Ant and Dec, the nature of comedy and tragedy, until their brows dampen and their shirts stick, and they’re forced to retreat under waiting parasols. A tourist bearing the pinkened skin of the Brit abroad hovers close. “Are you Rob Brydon?” he asks brightly. “Are you doing another series of The Trip?”

They are indeed. The Trip to Greece is the fourth instalment of the series directed by Michael Winterbottom, a show that has proved something of an unlikely success. It began in 2010, when the concept demanded a degree of patience on behalf of the viewer: the pair playing augmented versions of their real-life selves, longstanding friends and colleagues who embark on a culinary tour of northern England together. It was slow and subtle, largely improvised, and filled with jokes about Romantic poets, sticky toffee pudding and a glut of Michael Caine impressions. Since then, they have taken trips to Italy and to Spain, with plots encompassing personal and professional disappointments, romantic entanglements, ruminations on success, celebrity, masculinity, Byron and Don Quixote, alongside deep-fried artichoke flowers, sea bass carpaccio and octopus.

Series four carries them from Turkey to Ithaca, via Lesbos, Pilos, Athens and Hydra, a loose recreation of Odysseus’s journey home following the fall of Troy. Before they began shooting, Coogan tells me that he diligently read Homer’s epic poem, while Brydon, despite his best intentions, somehow did not.

“Steve’s northern, working-class chippiness works in his favour here, I think,” Brydon suggests. “Because he will make the effort. Whereas I’m sort of… I never get around to it.” Beside him, Coogan shrugs. “Well, I have an appreciation of knowledge,” he says. “Which is perhaps something that state school attendees have.” Brydon, who was privately educated until the age of 14, smiles and leans forward. “I have an appreciation of quizzes,” he says gently.

Time spent in the company of Brydon and Coogan occupies the sweet spot between fiction and reality. There they are, ribbing one another in the lobby of an Athens hotel, eating ice-cream, riding on boats, jumping off rocks into the sea at Hydra – and it’s only sometimes that the cameras are rolling. There is an immense fondness between them, their conversation carrying the happy rhythm of familiar comedy partners – the set-up, the punchline, the hamming of roles: Brydon, the affable family man and king of light entertainment; Coogan, the highbrow foil with a surfeit of Baftas, two Oscar nominations and a personal life that has often led to appearances in the tabloids.

“Greek mythology, I thought it was interesting, but I liked Greek philosophy more,” Coogan says, continuing his cultural appraisal. “And the world view of the three principal philosophers, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. For me, having had a struggle with religion [he was raised Catholic], it always baffled me that people stick to Christianity when there was a more nuanced, holistic approach to living your life that pre-dated it by a few centuries.” He is not against Christianity, he insists. “It’s just that loads of idiots have co-opted it. And that hasn’t really happened with Greek philosophy. You don’t think of stupid idiotic rightwing fundamentalist Greek philosopher followers.”

* * *

Part of The Trip’s allure is that, alongside mainstream references, many of its touchstones are unashamedly learned. This time there are impersonations of Tom Hardy and renditions of Frankie Valli’s Grease, but also long discussions of Aristotle’s Poetics, and a scene in which the pair enact the death of Sophocles. These are themes, Coogan argues, that are strikingly contemporary. “All that internal discussion within Greek philosophy, it feels so weirdly and strangely undated,” he says. “As you get older and you know you’re going to die, I think the feeling that these struggles and questions are all perennial, that they happened before you were born and they’ll go on after you die, and it’s part of a cycle – it’s nice, actually.”

There is a sense of an ending to this series. At a screening six months after filming ends, Winterbottom will bill it as the “fourth and last” instalment. The echo of Odysseus, and the storyline of “trying to get home after 10 years away” feels, he says, “like a natural end”. Whether or not this will prove true, his stars speak about their decade of making The Trip with a new kind of contemplation.

“I like the poignancy when I watch it back,” Coogan says. “But actually, you know what, the first Trip, to the north of England, I find that does have a lot of personal resonance, and I don’t really want to look at it. In the same way I can’t really look at 24 Hour Party People [the Winterbottom-helmed film in which Coogan also starred].” Raised in Manchester, it is the first series’ northernness that affects Coogan. “Because it’s so close to my heart, the north,” he says. “I just feel there’s something slightly maudlin about it.”

That could also be attributed to the grey skies, Brydon points out. “See, I sort of like grey skies,” Coogan says, wistfully. “I mean, not all the time, but when you see it on screen. I feel it’s sort of a pallor of sadness.” He hasn’t watched that series back in full, only caught glimpses of it as he’s channel-hopped. “It’s almost like an old photograph album, because it was us finding our feet…”

Brydon nods. “Exactly,” he says. “Now we go into it, there’s a template, we know what we’re required to do. But on that first one, having refused it several times, then decided to do it, it was like, ‘Well, what is it?’”

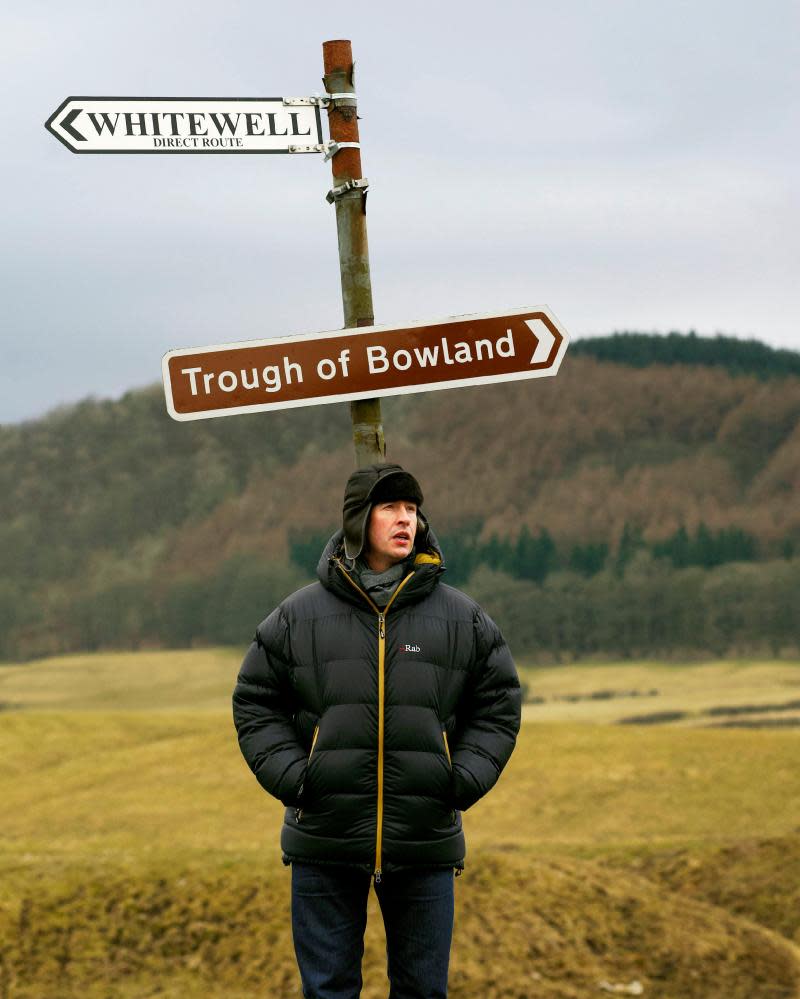

“I do remember after the first shoot, which was the Inn at Whitewell,” Coogan says, “when we’d done whatever we were doing, some Michael Caine stuff, and then maybe day three, I remember saying to you, ‘This is going to be good.’”

When Brydon watched the first series, he was, he admits “mortified”. He laughs. “I thought, it’s so slow! Nothing happens! Which of course became one of its strengths.” They discuss the enjoyment of a slower pace in a world that is increasingly fast and abbreviated. Brydon says he watches old talkshow clips on YouTube, in which conversation unfolds unrushed and unhurried. Coogan recalls the joy of rewatching Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation: “What I love about it is that it takes its time and allows you to look at the paintings. I thought, ‘This is really nice – I’m not thinking about something when it’s already moved on to something else.’”

In the years since The Trip began, we have seen other programmes that have found a similarly slow pace – Bob Mortimer and Paul Whitehouse’s Gone Fishing among them. “Paul phoned me to say, ‘We’re going to do this, how did you do The Trip?’” Brydon recalls. “And the difference is that, with us, there’s a constructed narrative. I envy Bob and Paul just going out and talking and having a nice time…” Coogan nods. “And not worrying if it’s funny or not.”

I have a lot of creative marriages. I'm an artistic bigamist

Steve Coogan

On The Trip, not only is the plot constructed, so is the pair’s relationship. Though they have known one another and worked together since 2000, when Coogan’s Baby Cow production company made Brydon’s series Marion And Geoff, their on-screen dynamic is more combative than in real life. “The meals we have? That’s not how we would have a meal,” Brydon says. “And I wouldn’t be poking him all the time, trying to undermine his success. I’m always saying, ‘Tell me about it! Oh brilliant!’”

“What I do sometimes is I go, ‘Right, I’m going to try to get provocative just to put a firework up its arse and see what happens,” Coogan explains when we meet again this month. “So it doesn’t just become too blokeily bland.” And a certain sharpness is necessary, he believes. “I think people like that: ‘Hold on, that’s a bit strong.’ It’s good to have those moments. It’s like teasing a child, or not giving the dog its treat.”

Over the course of four series, this blurring of reality has coloured how people respond to them in real life: seeing them as the clubbable Brydon and the prickly Coogan. “You can run away and hide, which is lovely,” Brydon tells Coogan. “I don’t have that. Because I front things as myself, because I am going, ‘Hey! Hi! Welcome to the show! I’m Rob!’”

Coogan smiles. “But in a way that is also an advantage, because people might think I’m a bit of a miserable twat,” he says, and they laugh.

“But it doesn’t bother you!” Brydon says.

“I’m not that bothered by it,” Coogan concedes. “I need to have enough people like me to want to see my shows, that’s all. Beyond that, I don’t really care.”

* * *

Throughout his career, Coogan has been deeply protective of his private life. To this day, he is moving forward with a claim against the Sun as part of a wider case against press intrusion, though he is unsure if it will ever make it to court. He ignores tabloid speculation about his relationships, and has no social media presence. “Sometimes people come up to me and say, ‘Oh, you know some people were slagging you off the other day?’” he says. “And I go, ‘Ah well, I had no idea.’ Because I don’t quite know where to find it.”

The choices the pair have made over the lifetime of The Trip underscore the divergence in their careers. Although Coogan will still revisit Alan Partridge, his most famous role, he has stepped deeper into film acting and collaborations with other writers, such as Tim Key, Jeff Pope and Sarah Solemani, via Baby Cow. A six-part #MeToo drama about a sexist producer and a younger female director, starring and written by Coogan and Solemani, was announced by Channel 4 last month.

Brydon, meanwhile, is a regular panel show presence, and recently revisited his much-loved role in Gavin & Stacey. Soon he will embark on a national tour, combining music and comedy. After speaking to Bob Mortimer about Gone Fishing, he has begun to contemplate some of the travelogue shows he is frequently offered, but still dreams of bigger roles – a Succession-type show, or a Wes Anderson film. Coogan is encouraging. “Rob did a series called Human Remains [a macabre comedy] for Baby Cow years ago, which I am still a huge fan of,” he says. “And because he went off in this other direction I still think that is something he needs to explore. I think you’ve hidden that under a bushel for a number of years.”

“The big difference between Steve and I, apart from anything inherent in our personalities, is I have five children,” Brydon continues. “Two of them are still of school age. So when Steve goes off for five months here and five months there, that holds no appeal for me. I don’t want to do it, neither am I able to do it. So you have to look at a person’s life. I have opportunities in America, but I can’t be out there.” He shrugs, contentedly. “So with him, I’ve said it till I’m blue in the face – I’m a proper fan of the guy, he’s terrific. Career-wise and work-wise, he’s kind of faultless.” There is a pause. “On a personal level, it’s a very different story.” Coogan starts to laugh. “Because personally, I can think of a lot of areas where his behaviour is appalling. But there’s nothing you can do about that.”

Coogan interrupts. “I have lots of different professional relationships, creative relationships, which is really great, because it brings different things out of me. And these relationships are like creative marriages. And so, in that respect, I’m an artistic bigamist. It’s a little bit of a midlife crisis: ‘I’ve got to get all this stuff done.’”

In 20 years, Brydon reminds him, he will be in his 70s. “Yes, so I feel I’ve got to get on with this stuff,” Coogan says. “But weirdly, there is a part of me that thinks, once I’ve got all this stuff done, then I can pick and choose a bit more.”

It’s possible that the death of Coogan’s father, in 2018, might have contributed to his desire to get things done. He references it a couple of times in conversation – showing me a video of his daughter playing the pinball machine that once lived in the Coogan family home; he found it in the attic after his father died and had it reconditioned. Later, he describes how he drew on the experience when shooting one of the series’ most poignant moments, only for Winterbottom to tell him it was “too on the nose, too overly demonstrative. And I said, ‘What? It was real!’ And he said, ‘Well, you’ve got to do it again.’” He was annoyed, he says, “because I felt I’d exposed myself. Emotionally, not physically,” he adds, as if to head off a Brydon quip. He retook the scene. “And he was right to make me do it again, because sometimes if you’re overdemonstrative then it’s disengaging,” he says. “It’s the repression of emotion that somehow draws people in. I think the British trait of not being open, in that Californian navel-gazing sort of way, makes us more interesting.”

Having worked with Winterbottom more than a dozen times, Coogan is delighting in his collaborations with a new generation. “I like working with young people,” he says, and slides his eyes to the left, waiting for Brydon to make the obvious joke. “I held back!” Brydon cries. “And that took so much. That’s drained me.”

Coogan laughs. “I see people who I think, ‘Well, I know how they do that’ and they might be technically funny, and they’re very good, but it leaves me cold,” he says. “And then sometimes I come across people where I don’t know why they’re funny, or they’re making me laugh for some reason I can’t quite work out.” Those are the people he wants to work with. “There’s a natural professional competitiveness in this industry,” he admits, “but when I see people who are really good at something I actually feel the reverse. I think, if they’re making me laugh I have no envy: I want to help them.”

He is on a roll now. “The other thing is, when you feel like you’ve become part of the furniture or the establishment, that makes me uncomfortable. I don’t like being part of the establishment, even though it means I’ve got a nice house…” “Several,” whispers Brydon. “… and all those trappings that go with it,” Coogan continues.

“Tell her about your cars,” Brydon says. “And material things like cars,” Coogan nods. “Cars are weird,” he adds, “because cars are a way of me disengaging from anything creative or ethical – it’s like a brain holiday. I don’t actually drive them all. I use public transport a lot,” he adds. “But I collect them. Some people meditate. I can’t do that. So I source old cars and restore them.” “You mechanictate,” Brydon says.

Coogan exhales. “But the thing is, I don’t want to become a staid, conservative with a small c, member of a club. I don’t want to hang out with people who have status and money, and so I kick against it. Any captain of industry, any billionaire, anyone who people look up to through dint of the material success – I couldn’t give a shit [Coogan recently played a thinly veiled version of disgraced retail mogul Philip Green in Winterbottom’s Greed]. Not only am I ambivalent about them, I try actively to avoid them because I don’t think it’s good for you. Not from any great moral standpoint, or grandstanding – I think it’s bad for you creatively. Keep away from people like that if you want to say anything relevant. It’s like rock bands who do two good albums, and then start hanging round with famous people and taking drugs, and all they see is the inside of hotels. And then the third album’s shit because they’ve got nothing to say. So I’ve tried to avoid that.” Brydon looks up. “What sort of bands?” he asks. “Just give us a couple of names.” “Well Oasis, by their own admission,” Coogan says. “They know their third album was shit because they lost the plot.”

Related: The Trip: a show about death that deserves to live on

But this is series four of The Trip, I say. “Touché!” shouts Brydon. Coogan laughs. “I would say that I think series four is probably the weakest,” he says. “No, I’m being disingenuous – I think people who love The Trip will love it as much as they love the others.” Brydon agrees. “When James Taylor releases a new album it sounds like a James Taylor record,” he says. “And I think this will feel just like The Trip.”

* * *

Back in Hydra, Coogan and Brydon sit on a restaurant terrace overlooking the turquoise sea. Brydon sips a glass of sauvignon blanc, and the pair assess the plate of seafood before them that looks “like a fishy Jackson Pollock”. The conversation winds on through the hot afternoon, through many takes and makeup touch-ups, through the muttered advice of Winterbottom and the arrival of courses and a tortoiseshell cat that winds gently around the table leg. “This couldn’t be more idyllic, could it?” Brydon says, before the conversation meanders once more – to Al Pacino, the Queen’s honours, Mick Jagger, hydroplanes, body hair, Chris Hemsworth and Aristotle. It is a conversation that could quite happily run for ever. But soon the sun dips a little, and the shadows lengthen, and Brydon at last calls for the bill.

• The Trip To Greece is on Sky One from 3 March.

If you would like your comment on this piece to be considered for Weekend magazine’s letters page, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).

Yahoo News

Yahoo News