Running on fumes: May and her attorney general plough on

The last few weeks haven’t been kind to Geoffrey Cox. When he agreed to become attorney-general it was strictly on the understanding that his appearances at Westminster would be kept to the bare minimum. After all, he didn’t take a massive pay cut – he was formerly a top QC – in order to have to do more work.

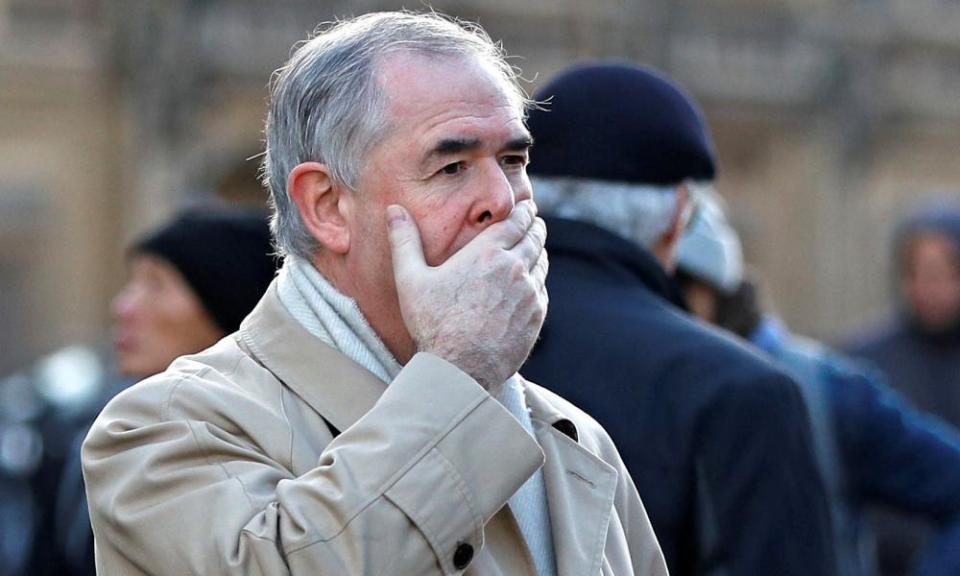

Since then he has been roped into spending two and a half hours on his feet trying and failing to explain why it was OK for the government not to hand over the legal advice that parliament had instructed it to provide. And in the process both his pride and his reputation have taken a bit of a hammering. As he sat on the front bench, the aura of invincibility had gone. He looked smaller than usual. Almost foetal.

Inevitably the first questions were on the subject of contempt. Not of the law, but of parliament. Cox hauled himself to his feet. “It is always a serious matter for any minister to find himself at odds with the House,” he said sadly.

His liquid baritone appeared to have dropped a few staves and lost its carry. Stress was turning him into a barely audible basso profondo. The realisation that he had missed his chance of a transfer to the West End. Only his cat would now see his Lear. The only offer his agent had received had been for the pantomime dame in Blackpool. Lights, camera ... but no action.

Cox stoically kept going. He was a professional after all and even an old ham had standards. It was important that the principle of his legal advice to government should be kept confidential. After all, if he was to be held accountable to the entire country, he might need to cover his back. But even he couldn’t sound convincing in his insistence that his entire legal advice on a 585-page document had run to no more than 20 pages. There was no applause. No demands for an encore. He left in silence. That it had come to this.

Over in Brussels, the principal architect of his misfortunes was having more than enough troubles of her own. Theresa May was running on fumes. Her batteries were almost dead and she was out of memory. All but obsolete. The passing thrill of having survived a no-confidence vote the night before had given way to numbness. She could feel nothing but her own sense of incompetence and failure.

The numbers just didn’t stack up. More than half her backbenchers had voted against her. Possibly even some of her ministers. You couldn’t trust any of them in a secret ballot. Come to think of it, she couldn’t actually remember how she had voted herself. What’s more, plenty of those who had voted for her still wouldn’t back her deal. So she was screwed. Her Brexit deal was an ex-Brexit deal.

May tried to make herself invisible as she passed the news crews on her way into the council chamber, but she couldn’t ignore the persistent calls for a fragment of her time. She had heard what backbenchers had said about the backstop and she was focused on getting the deal over the line. She didn’t have a clue how, as she wasn’t expecting any breakthrough. But something miraculous might turn up. She was plodding on, because if she stopped it would all be over. And the one thing worse than her current life was the thought of someone else doing it just as badly.

Wednesday had been difficult and she now fully accepted she wouldn’t be leading the Tories into a general election in 2022. Though she might do so in 2019, 2020 or 2021. No one was going to take her alive. She would fight on to the bitter end, she said, accidentally handcuffing herself to the railings.

The other European leaders looked on in amazement. The UK’s Brexit incompetence may have started out as an amusing embarrassment but now it was just downright annoying. Enough was enough. “WHAT BIT OF ‘YOU INSISTED ON THE RED LINES AND YOU SIGNED OFF THE LEGAL WITHDRAWAL AGREEMENT’ DON’T YOU UNDERSTAND?” yelled Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel, kicking a door in frustration.

All of it. Somewhere in an attic in Downing Street a picture of May got noticeably younger. She was fine. It was fine. Everything was fine. She was a winner. A winner on borrowed time.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News