Russia may loosen budget purse strings as election draws near

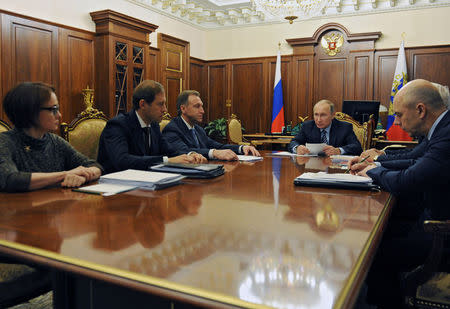

By Andrey Ostroukh MOSCOW (Reuters) - Russia has reassured markets by setting tough limits on spending and the deficit over the next three years, but the Kremlin may loosen its targets ahead of a presidential election in 2018, officials familiar with the matter said. The government released the draft three-year budget with fanfare, trumpeting it as a sign of stability after it temporarily switched to one-year budget planning for 2016 to survive an economic crisis. The draft includes a freeze on spending near the 2016 level of 16.4 trillion roubles ($257.05 billion), while the budget deficit will shrink to less than 1 percent by 2020 from nearly 4 percent in 2016. Many of those figures are flexible, however, and are likely to change as the 2018 election approaches, according to two officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity. President Vladimir Putin is widely expected to seek another term. One of the officials, who is familiar with the finance ministry's budget planning, said the plan for 2017 is more or less realistic, but that figures for 2018 and 2019 are more aspirations than rigid targets. Another government official said the budget plan was of a technical nature and will be subject to revision in the future. Some economists focused on Russia also view elements of the three-year draft budget as wishful thinking given the likelihood that political pressure will push up public spending. Wage increases for public sector workers and military personnel, to ensure they turn out to vote for the Kremlin's candidate, could be a particular threat to budget targets. "The plan for 2018 and 2019 could have been proposed just for the sake of proposing, but not for living according to this plan," said Denis Davydov, chief analyst at Nordea bank in Moscow. "We are very likely to see adjustments to the plan." The finance ministry said it could not provide an immediate comment. POLITICAL PRESSURES Russia sank into an economic crisis in 2014 as plunging oil prices sent the rouble to a record low, and holes in the budget had to be plugged from state coffers. Sanctions imposed by the West in response to Moscow's role in the Ukraine conflict exacerbated the downturn. The budget plan for 2017-2019 is set to be reviewed and approved by parliament before Putin signs it into law by the end of the year. It includes a pledge by the government not to increase the tax burden, which means that unless the oil price goes up significantly, the only way to finance the extra spending may be through borrowing more than projected. The government could save money by pushing up the retirement age but has shown little appetite for such a move. According to Chris Weafer, a senior partner at Macro-Advisory, a Moscow-based consultancy, the three-year budget with its tough fiscal targets was intended to project Russia's economic self-sufficiency to the outside world. "It's about giving a message to the West that we're not relying on you," Weafer said. (Editing by Christian Lowe and Catherine Evans)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News