Sacha Baron Cohen: After Borat, what’s left for the savage satirist?

Thirteen years ago Sacha Baron Cohen announced that he was retiring the character of Borat Sagdiyev, the Kazakh journalist in the ill-fitting grey suit and Saddam moustache. It was a logical step in what is, as Baron Cohen has called it, a “self-defeating” line of work.

Borat’s satirical power was dependent on being unknown. But the global success of the 2006 mockumentary feature film Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, for which Baron Cohen won a Golden Globe, rather blew the fake Kazakh’s cover. Hence his discontinuation.

Unlike most celebrity retirements, this one appeared to be permanent. And aside from a brief appearance a couple of years back on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, Borat was as good as buried. Now, however, he’s back in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan.

Borat, his fans will be relieved to know, hasn’t changed much, but the world has. In 2006, when the first film came out, George W Bush was president, Iraq was in flames and North Korea claimed to have conducted its first nuclear test. No garden party but, looking back, it seems almost a golden era of sanity.

The thought that Donald Trump would become president would have seemed only slightly less ridiculous than Borat ending up in the White House. Like Shakespeare’s proverbial coward, satire has died many times, but seldom has reality made it look quite so redundant as over the past four years.

Baron Cohen is keenly aware of the shift in the political culture. “In 2005,” he recently said, “you needed a character like Borat, who was misogynist, racist, antisemitic to get people to reveal their inner prejudices. Now those inner prejudices are overt. Racists are proud of being racists.” They have been empowered, he explained, by a president who is “an overt racist, and overt fascist”.

That president, who walked away from a TV interview with Baron Cohen’s Ali G character after less than a minute in 2003, is no fan. “I don’t find him funny,” Trump said last week. “To me, he’s a creep.”

Trump’s America, as it appears in the film, is a familiar one from the Louis Theroux genre of documentary-making, richly peopled with faultlessly polite freaks and likeable rednecks with unpalatable opinions. If making fun of conspiracy theorists and antisemites doesn’t break any new ground, it’s not going to upset anyone, except for conspiracy theorists and antisemites.

The watching world, however, has become much more ready to take offence and Baron Cohen’s brand of humour is not ideally suited to modern woke sensibilities. He is from the generation of comedians, including Steve Coogan and Ricky Gervais, who invented winningly grotesque characters to ventriloquise the unsayable. By this method, a shocking racist comment could be transformed into a stinging comment on racism.

Some critics saw it as a dishonest transgression, arguing that Ali G, the wannabe black character who brought Baron Cohen’s initial fame, was little more than a postmodern version of The Black and White Minstrel Show. That seems a rather crude reading, but it’s hard to imagine that in an era of righteous cancellation, in which cultural appropriation is a cardinal sin, Baron Cohen would “get away with it” today.

That Borat is from Kazakhstan, a country with a tiny expat community in the UK and about which censorious Generation Z’ers know very little, has afforded Baron Cohen some protection from the Twitter mobs. But cracks about the Kazakhs’ backwardness, sexism, homophobia and antisemitism hark back to a more robust understanding of irony. Younger audiences may not bother with any layered interpretations and just decide that it’s racist.

There is no doubt that the Kazakhstan government was not amused. It threatened him with legal action in 2005 and removed his Kazakhstan-registered website. In the character of Borat, Baron Cohen replied: “I’d like to state that I have no connection with Mr Cohen and fully support my government decision to sue this Jew.”

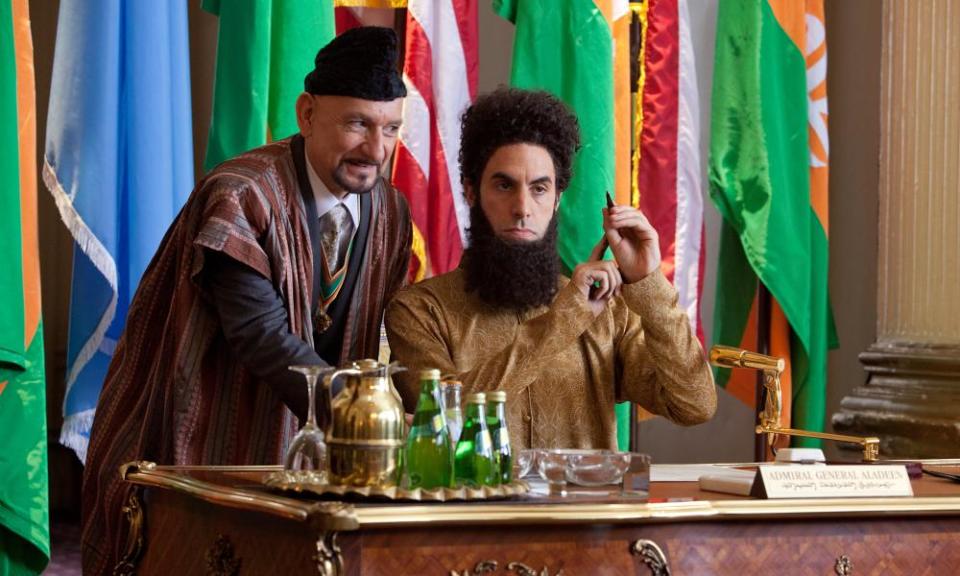

In any case, this is almost certainly Borat’s last outing. Baron Cohen has plenty of other projects to keep him occupied. The signs are that he is expanding into drama, after sporadic ventures in the past, including Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd and Tom Hooper’s Les Misérables. While Borat Subsequent Moviefilm is released on Amazon Prime, over on Netflix the big hit of the moment is Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7. It’s about the court case involving leading figures of the counterculture arrested after protests at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. Baron Cohen is quite brilliant as Abbie Hoffman, an early advocate of flower power.

Aware that Hoffman’s provocative style was heavily influenced by Lenny Bruce, Baron Cohen portrays him as a kind of natural standup comedian. Having played the surrealist prankster and buffoon throughout the trial, Hoffman is called on to make a rousing speech on the witness stand. Baron Cohen has to prove his acting chops in this big climactic scene.

Sorkin has said that the sense of anticipation around the set before the Londoner filmed the scene reminded him of when Jack Nicholson performed his famous courtroom scene in A Few Good Men. “Everyone wanted to watch. One hundred and twenty extras didn’t care that the camera wasn’t on them, they stayed to watch.”

And, despite wrestling with a tricky Boston accent, Baron Cohen nails it. Nor is it the only speech that has brought him attention in recent times. Upset by the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017, he offered his services to the Anti-Defamation League, whose director, Jonathan Greenblatt, asked him to give the keynote speech at last year’s ADL summit.

Though wary of celebrities who use their fame to promote their political views, Baron Cohen delivered what he has said was his first “major speech in my own voice”. One of his main targets was Facebook. Had the social media platform been around in the 1930s, he said, “it would have allowed Hitler to post 30-second ads on his ‘solution’ to the ‘Jewish problem’”.

The speech led to the Stop Hate for Profit campaign that caused hundreds of companies to temporarily remove their advertising from Facebook. It was a high-profile stance for a star who, when not in character, likes to stay out of the public spotlight. The reticence is a mixture of natural shyness and professional pragmatism – the more he’s seen as himself, the less, he thinks, he’ll be believed as someone else.

This reservation has left a slight air of mystery around Baron Cohen. His biography has a credible spine but is lacking in animating flesh. Brought up in Hampstead Garden Suburb by Jewish parents, a dance teacher mother and a journalist father who went into menswear, he attended the Haberdashers’ Aske’s boys’ public school.

At Cambridge, where he studied history, he joined the Footlights and appeared in Fiddler on the Roof. Legend has it that on leaving Christ’s College he gave himself five years to make it as a comedian. After a brief stint as a male catalogue model, he began performing at a comedy club in Hampstead, and worked for a couple of small satellite channels. At one of them he created a spoof character based on the hip-hop DJ Tim Westwood, the bishop’s son who speaks like he’s down wiv ver kidz.

From there Ali G was born and, as the five-year deadline was closing in, he grasped his opportunity on Channel 4’s The 11 O’Clock Show in 1998. The rest is hysterics. Now ensconced in Los Angeles, Baron Cohen forms half of that most rare of Hollywood entities – a long-lasting joint-celebrity marriage – with the Australian actress Isla Fisher. They have three children.

Baron Cohen has been mining excruciating moments of comedy gold for over 20 years. There is another collector’s item in the latest film featuring Rudy Giuliani and Borat dressed as a woman, offering the Trump adviser and former New York mayor anal sex. There are only so many times that he can be the subject of a sentence like the last one. Next year he turns 50. Enjoy him while you can.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News