Sally Jacobs obituary

In a career ranging from Peter Brook’s greatest productions at the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Marat/Sade in 1964 and A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1970, to operas at Covent Garden, and new plays by Timberlake Wertenbaker and Stephen Jeffreys, the designer Sally Jacobs, who has died of cancer aged 87, was an important figure in theatre of the last half century.

But the continuity of her career was not always apparent. Although she returned to Stratford-upon-Avon in 1979 to design Brook’s revival of Antony and Cleopatra, she had by then spent a decade in Los Angeles, where she had worked at the Mark Taper Forum and with brilliant American artists of that generation such as the directors Joe Chaikin and Richard Foreman, and the playwright Sam Shepard.

And in 1973 she had started work again with Brook on The Conference of the Birds in New York, continuing the project of improvisations and drawings based on an allegorical poem by a 12th-century Sufi poem – puppets and masks, costumes of gorgeous silk plumage – at his Bouffes du Nord theatre in Paris, the African tour so vividly documented in a 1977 book by John Heilpern, and its triumphant re-emergence at the Avignon festival of 1979.

When she returned to Britain full-time in 1982, she was in demand as a teacher at Central School of Art and Design, and the Slade School of Fine Art, having spent some years in the congenial and well-funded US theatre schools that maintain professional contacts, such as Rutgers in New Jersey and the University of California in LA.

Her sensational designs for Andrei Serban’s 1984 production of Puccini’s Turandot at the Royal Opera House – a production that stayed in the repertoire for more than 30 years – developed the Chinese circus impulse behind the RSC Dream into a Chinese theatre of stark, violent pageantry.

Sally was born in Mother Levy’s Jewish Maternity hospital in Whitechapel, east London, at around the same time, and in the same place, as Lionel Bart and Arnold Wesker. Her parents were Bernard Rich, a furrier, and his wife, Esther (nee Bart, no relation to Lionel), a milliner.

She was educated at Dalston County secondary school in Hackney, St Martin’s School of Art and the Central School of Arts and Crafts.

Money was tight, so she learned shorthand and typing in order to do office work to contribute to the household while she continued her studies. While working as a secretary at a film copyright agency in Soho for £3 a week, she met a writer there, Alexander Jacobs, who paid her parents so that Sally could concentrate on art.

She was still a teenager, but she and Alexander stayed together, and married in 1953. Their respective careers took off, hers with the RSC, his with the film director John Boorman, for whom he wrote two Hollywood screenplays, Point Blank and Hell in the Pacific. Sally’s second RSC production was Women Beware Women directed by Anthony Page at the Arts theatre in 1962, with John Thaw and Nicol Williamson in the cast. She was interviewed by Brook after she had seen his production of King Lear with Paul Scofield in the same year and was invited by him to join the first workshop of his Theatre of Cruelty season in 1963.

This radical strain in the RSC’s work, inspired by Antonin Artaud’s theories of disturbing, cathartic theatre, not “filth” (as the developing row implied), climaxed in the staging at the Aldwych of Peter Weiss’s play Marat/Sade, set in the bath house of an asylum where the inmates, directed by the Marquis de Sade, re-enact the murder of Jean-Paul Marat by Charlotte Corday.

Jacobs placed the extraordinary ensemble riot of orgiastic violence, disputation and lunacy on a pattern of small pools sunk in the floor, covered with duckboards, with benches around the periphery, pipes and water jets everywhere, a fully lit stage, no props, no black-out in the audience, and no curtain. Her design was as powerful a factor in the overwhelming impact of this show – the actors applauded (ironically) the audience at the end – as were Richard Peaslee’s music and the performances of Glenda Jackson, Ian Richardson and Patrick Magee.

She found time to design costumes for two films: Clive Donner’s Nothing but the Best (1963), written by Frederic Raphael, with Alan Bates, and Boorman’s Catch Us If You Can (1965), with the Dave Clark Five, on which Alexander was an assistant producer.

Marat/Sade was followed by US (1966), a documentary-style protest show for which Jacobs designed a sort of dangerous, volatile playground featuring a large American soldier with a rocket for a penis. She created more conventional RSC productions – Love’s Labour’s Lost for John Barton in 1964 and Twelfth Night (Diana Rigg as Viola, Ian Holm as Malvolio) for Clifford Williams in 1966 – but A Midsummer Night’s Dream was the one everyone talked about.

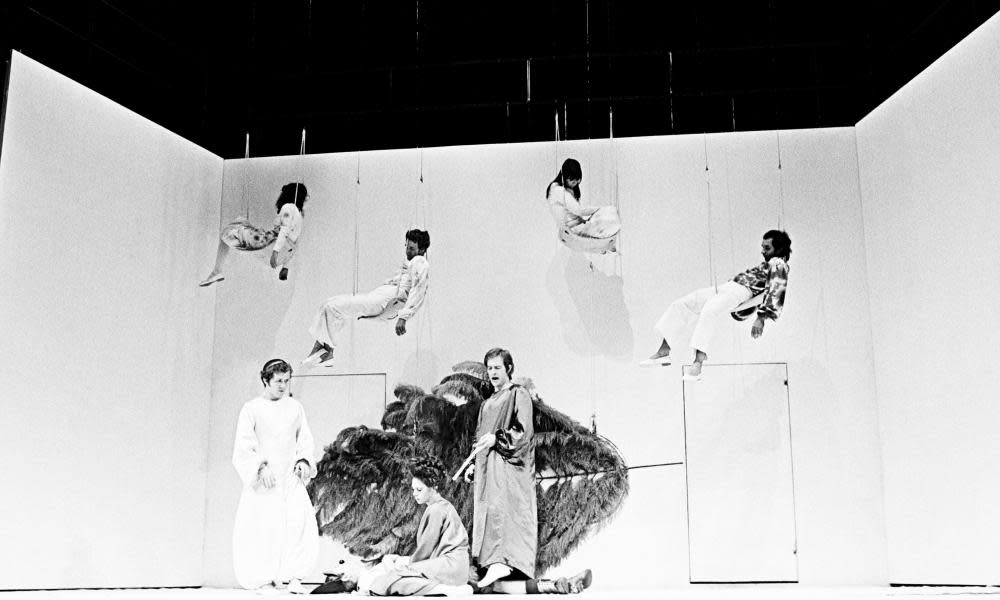

Watching Chinese acrobats with Jacobs, said Brook, gave him the key: “a human being who, by pure skill, demonstrates joyfully that he can transcend his natural constraints, become a reflection of pure energy. This said ‘fairy’ to us. A new imagery could begin to flow from Sally’s rich creativity.” A white box for the set – which could be gymnasium or playground or forest – mechanicals in string vests and flat caps, Oberon and Puck sitting on trapezes, metal coils for trees, Titania in her bower of scarlet flowers, nothing up their sleeves, all in white light. The production was an international smash hit and toured for years.

Jacobs was able to continue with Brook even as she and Alexander settled in Hollywood, where his work now decreed his presence. Her American theatre portfolio grew, but the marriage was failing – they separated, but never divorced, and Alexander died in 1979.

At Covent Garden, Jacobs followed her triumph on Turandot with another Serban production, Fidelio in 1986, for which she found engravings expressing the opera’s themes of redemption, freedom and the soul’s release from suffering; the set was a vast dungeon which finally breaks open as Leonora rescues Florestan and sunlight floods the stage. For the ENO, she also designed a critically approved Eugene Onegin, directed by Graham Vick, and David Freeman’s 1996 version of Zimmermann’s modern classic Die Soldaten.

For Wertenbaker’s Three Birds Alighting on a Field (1991) at the Royal Court she supplied a maze of transparent Perspex, empty frames (it was an art world satire) and a beautiful landscape, while for Jeffreys’ Elizabethan burlesque The Clink – one of four new plays she designed for the Paines Plough theatre company in the 1990s – she placed a jagged wooden stage against a backdrop of the outline of England.

Like so many great designers, her working life began and ended in the art colleges and among students and aspirant professionals. Alongside her teaching, she remained active in her studio in Muswell Hill, north London, making performance art, installations and paintings. Her archive is held by the Harvard Theatre Collection.

She is survived by Toby, her son with Alexander, and two grandchildren.

• Sally Marie Jacobs, designer, born 5 November 1932; died 1 August 2020

Yahoo News

Yahoo News