‘Saved from a horrible fate’: Legal heroin prescribed to hundreds of UK drug users, figures reveal

Hundreds of people addicted to heroin in the UK are benefitting from a free legal supply of the drug, new figures show.

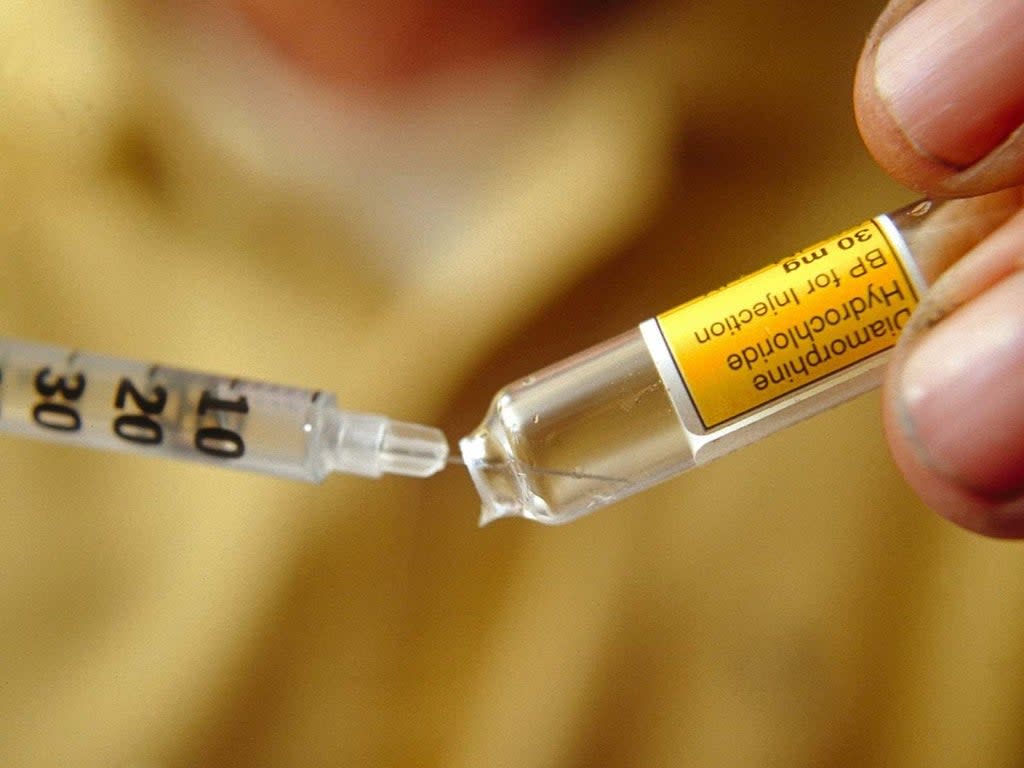

The Independent can reveal that 280 people received a prescription for diamorphine – medical-grade heroin – in 2017-18, via a freedom of information request to Public Health England (PHE) by Release, a drugs charity offering legal advice and support.

Under PHE guidelines, diamorphine is usually offered as a last resort after other forms of treatment, such as methadone and buprenorphine, have proven unsuccessful.

“I’ve seen firsthand how diamorphine could help people recover to the point where they were able to work, experience liberation from a cycle of repeated criminal justice involvement, be present for their families, and have hope where previously there was none,” said Dr Prun Bijral, medical director at the UK’s largest third sector drug treatment provider, Change Grow Live.

But the treatment is “under threat” due to severe cuts to drug services and the planned removal of the Public Health Grant, said Niamh Eastwood, chief executive of Release, which often works with people who fear having their prescription removed.

“Any decision to remove this treatment could lead to more people dying,” said Ms Eastwood, referring to Thursday’s figures showing drug-related deaths remained at the highest level since records began, with a 16 per cent spike in 2018.

The threat of a diamorphine prescription being removed could cause “untold damage” to those reliant upon one, said Ms Eastwood. “It can create a sense of fear and insecurity and can cause significant distress to individuals in this position.”

She warned the removal of an individual’s treatment could jeopardise their employment, and created a “real risk” of these previously treatment-aversive drug users returning to street heroin.

The UK has provided heroin users with diamorphine since 1926. Often referred to as the British System, the practice was the country’s main form of treatment until 1967, during which periodthe number of known heroin users rarely rose above 1,000.

“We led the world in providing diamorphine under the British System; a pragmatic and reasoned approach to a serious issue,” said Dr Bijral. “Diamorphine is just another opioid medication, used in every hospital, every day, and has been an essential medication for well over a century.”

While hundreds of people have received the drug under this legal framework ever since, the British System was largely phased out in the late 1960s – a move the then Home Office drugs chief Bing Spear branded “an unmitigated disaster” in a book detailing his time in office.

The “Trainspotting” heroin epidemic that followed “was a direct result of gifting the market to organised crime”, said Neil Woods, who spent 14 years as an undercover detective and is now chairman of LEAP UK, a coalition of law enforcement figures calling for an end to the war on drugs.

“There was no association between drugs and crime at all before the British System ended,” Mr Woods said, referring to the tactic of encouraging heroin users to turn others onto the drug in order to fund their own habit. “When heroin was controlled by doctors there was no incentive to find new customers.”

In 2019, the Home Office estimated the social and economic cost of drugs supply in Britain to be £20bn, an increase of £9.3bn since 2010-11.

Diamorphine prescription is “the single biggest blow you could cause to organised crime, and the most effective protection for children sucked into the ‘county lines’ heroin trade“, said Mr Woods.

Critics of diamorphine-led initiatives allege they de-incentivise individuals to stop using drugs.

Speaking of plans to prescribe diamorphine at a heroin-assisted treatment centres in Glasgow, Dr Neil McKeganey told the Scottish Sun: “The treatment of people who are addicted to heroin should be focused on helping them into a drug-free state, not continuing and facilitating their dependence.”

Dr McKeganey, who has faced scrutiny since June after it emerged he received funding from a heroin substitute manufacturer in 2012, said: “It should be focused on enabling them to recover and I fear this will achieve the opposite.”

Many expertswarn against framing outright recovery as at odds with harm-reduction measures, and several told The Independent they believe this has contributed to the rise in drug-related deaths since 2012.

Dr Russell Newcombe, who helped pioneer the harm reduction philosophy in the Eighties, recalled interviewing the patients of Dr John Marks, who treated around 450 drug users in Merseyside with smokeable heroin for a decade starting in 1988. There were no drug-related deaths at the clinic during this period.

“Almost all the people on diamorphine scripts I spoke to said their lives had improved dramatically, and John had literally saved them from a horrible fate,” he said.

John Marks’s clinics were closed in 1998 after international media attention drew pressure from national and regional authorities. Over the following two years 41 former patients had died, 20 within six months.

“It would be a shame if we lost the organisational and national memory on how diamorphine can be prescribed effectively in the community,” said Dr Bijral.

Around 0.2 per cent of the 141,189 opiate users engaged with health services in 2017-18 received diamorphine in England and Wales, PHE data shows.

Despite the cuts to services it is vital that this treatment option be not maintained but expanded, Ms Eastwood said.

She also urged authorities facing funding shortages not to de-prioritise the introduction of heroin-assisted treatment centres, where high-risk heroin users can self-administer prescribed diamorphine two to three times daily under the supervision of health care professionals.

“Considering that over 50 per cent of people who died from opiate-related deaths [in 2013] had not been in contact with treatment services in the [previous] five years, we need to have a treatment system that provides real options to people who are dependent on heroin,” Ms Eastwood said.

Diamorphine is considerably more expensive than opioid substitutes.

Under Home Office regulation the drug must be provided in freeze-dried ampoules costing £9 or £10 for 100g, totalling around £14,000 a year per patient. Tablet and powder forms of diamorphine are considerably cheaper.

It’s widely accepted that this better preserves the drug, but one expert said the regulation is fuelled by paranoia that other forms of the drug could be more easily sold on the black market. Home Office experts could not provide The Independent with a reason for the stipulation.

“If the government really tried it could acquire powder heroin at a competitive rate,” said Mr Woods, whose book Drug Wars details the British System. “Ampoules are expensive, there just needs to be some thought put into it.

“Even if heroin treatment appears more expensive than the less effective substitutes, it’s far more cost effective when you consider the benefits to society in reducing the associated thefts, and the dominance of organised crime.”

Two heroin-assisted treatment centres, in Glasgow and Cleveland, are set to open in 2019.

This article was amended on 1 October 2021. It previously referred to 0.002% per cent of the 141,189 opiate users engaged with health services in 2017-18 receiving diamorphine in England and Wales, but that percentage was incorrect and should have read 0.2%.

Read More

Quarter of petrol stations still dry, retailers say

Climate strikes: Why are young people across the world taking to the streets?

Botox and lip filler injections banned for under-18s

Do you actually care about the record number of drug-related deaths?

London teenage girls used by gang to flood Welsh town with drugs

How ‘just say no’ approach is fuelling Scotland’s drug death epidemic

Yahoo News

Yahoo News