Scarred for life: the Himalayan towns sinking into oblivion

Beneath the dark, jagged peaks of the Himalayas, Ashish Joshyal surveys a crater where his house once stood. Behind him, the bright green walls of his kitchen and living room tilt at jarring angles, some collapsed altogether. The floor is a sea of rubble and stone.

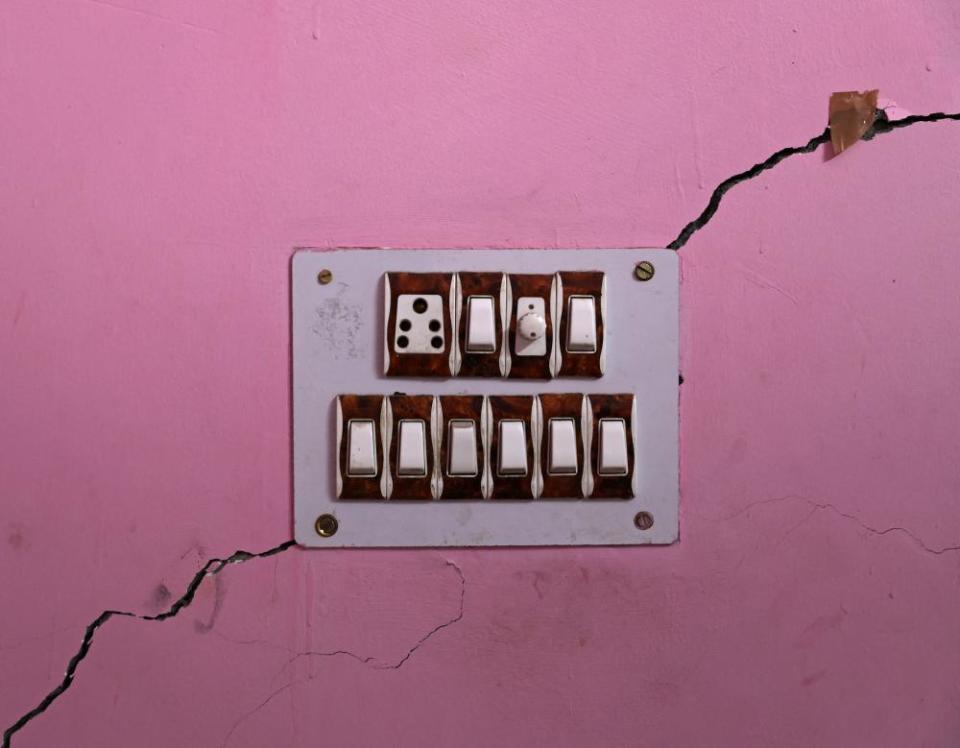

Not long ago, Joshyal’s house stood upright. But, like hundreds of others in Joshimath, a sacred town in the Indian state of Uttarakhand high up in the Himalayas, his problems began one night in early January. Cracks appeared in his roof, then crept down the walls. They got wider and wider until they were gaping chasms.

Finally, at the beginning of February, the front porch and the floors began to sink and the whole house gave way.

“You can’t imagine how it felt, it is a tragedy for us,” says Joshyal, 30, amid the ruins. He lived here with seven family members, including his wife and children. Now they are living in a temporary camp in a nearby school.

“Not only my house but my fields have gone,” he says, pointing to a grassy patch below, now jagged with fissures. “How will we ever get so much back in one lifetime?”

In the neighbouring fields, Bishweshwari Devi, 57, hitches up her yellow sari as she crosses the land she once used to grow vegetables and grains. It has now slid deep into the mountain and lays ruptured and ruined.

“It has fallen five feet in the past two weeks,” says Devi, who has also been forced to leave her home due to cracks.

“Joshimath is in turmoil. The fields have been ruined, the houses are falling apart and the people here are devastated. My own house was like heaven for me. We put all our savings into building it. Now it is not even safe for our cows.”

Joshimath is sinking and, according to locals, it is sinking fast. All across this town, which clings to the steep side of the mountain, more than 900 houses are marked with an ominous red X, meaning they too have been ruined by subsidence and cracks, or in some cases crumbled entirely as the ground swallows them up.

Roads look as if they have been uprooted by an earthquake, and more homes, some newly built, crack and sink by the day. Two multistorey hotels have been bulldozed to prevent disaster, and many more homes are set to be flattened.

More than 200 families are living in temporary shelters, often five or more to a room. Many still go back to their sinking homes every day to cook and sit together, unable to bear abandoning them completely.

For the older residents, the disaster has been particularly painful. Padmanabh, 79, stands next to his traditional stone hut, also an important local shrine, where he has lived and worshipped his entire life. The cracks in the foundations are evident but he is still living there, tending to his cows.

“We are frightened,” he says softly. “My god is here, people have cleansed their sins here. Where will I go?”

Why is Joshimath sinking? That is a contentious and divisive topic. What is certain is that the town, already built on the fragile geological foundations of ancient landslide debris, has been under immense and growing pressure for years – and its future is now in peril.

Joshimath sits 6,000ft up in the Indian high Himalayas, a mountain range steeped in spiritual meaning for Hindus who believe it is the abode of the gods. Nanda Devi, a peak visible from a point above the town, is said to be a manifestation of the Hindu goddess Parvati. The town is close to one of the most sacred Hindu shrines of the Himalayas, Badrinath temple, where millions of salvation-seeking pilgrims travel every year.

As far back as 1976, scientists cautioned that any heavy construction, tunnelling or disturbance of the Joshimath slope could have serious consequences. The warnings were ignored, and an unregulated sprawl of homes, multistorey hotels, shops and restaurants was allowed to spring up along the mountainside. Trees, which stabilised the ground, were cut down and drainage was neglected.

Himalaya is a unique ecosystem that sustains billions of lives but it is being bruised, reshaped and exploited

John Keay, historian

To worsen the danger, an army base was moved into the town, building barracks, schools and a hospital, and the population of this small mountain community soared.

An initial report into the subsidence in September last year by the Uttarakhand state government blamed a combination of unstable terrain, over-construction, climate change and river erosion. But locals, and some experts, allege that this is not the full story.

Instead, they say the disaster engulfing Joshimath is part of a wider pattern emerging across Uttarakhand as the fragile mountain terrain of the state, which is full of vulnerable fault lines, is now being blasted, chiselled and penetrated by development projects. More than 100 hydropower projects in varying degrees of construction stand almost bumper to bumper along its holy rivers, and a vast network of highways and railways is under construction.

Resistance by environmentalists has been fierce. In 2018, GD Agrawal, a professor and activist, died after going on hunger strike in protest at the hydropower projects planned along the holy Ganges river.

Joshimath has been caught up in this development spree. Since 2006, construction has been ongoing on the Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower project, about 10 miles from the town, on the Dhauliganga river. Then, in September, blasting and drilling began for a road at the base of Joshimath’s slope, part of a flagship 900km project across Uttarakhand launched by prime minister Narendra Modi in 2016.

The road has faced multiple legal challenges from environmentalists and been linked to cracks and subsidence in other towns. This stretch below Joshimath was red-flagged by experts as too risky, but the supreme court allowed it to go ahead.

India is not alone in exploiting the Himalayas’ resources. China has been on a decades-long development push in the Tibetan Himalayas, a source of concern to India, which has been rushing to catch up. In Nepal and Pakistan too, vast dams are being built on important glacial rivers.

“Himalaya is a unique ecosystem that sustains billions of lives,” says the historian John Keay, who recently authored Himalaya: Exploring the Roof of the World. “But it is being bruised, reshaped and exploited with really no overall plan for it, no internationally agreed standards of exploitation and no safeguards against the impacts of roads and dams across regions.”

India is said to have the fifth-largest hydropower capacity in the world, and more than 70% of that capacity is in the Himalayas. As successive governments have sought ways to secure India’s growing need for electricity, hydropower dams – considered to be green energy despite displacing communities and submerging forests – have been touted as an essential part of India’s progress and development.

Yet experts have increasingly questioned the wisdom of building huge dams in an area at very high risk of earthquakes and disproportionately affected by climate change-inflicted disasters, particularly as glaciers melt at alarming rates. The high risk also makes hydropower much more expensive, and it now costs almost three times as much as solar energy to produce in India.

***

For some in the state, the consequences of the hydro boom have already proved devastating. Years before Joshimath started sinking, 150 miles away in the village of Pipola Khas, cracks, subsidence and lopsided walls had become a way of life.

The village sits on a slope overlooking the Tehri dam reservoir, one of the largest hydropower projects in India, which involved the submersion of more than 100 villages as well as forests and fields. It began operating in 2005. Five years later, the cracks began to show in village homes. A government report in 2011 acknowledged the dam reservoir was causing subsidence and slope erosion, but locals say the authorities have done nothing for them, even as it continues to get worse.

Dozens of families have now abandoned their homes, some of which have been split wide open. Others with nowhere to go are forced to live with the deep cracks and chasms.

Tears fill the eyes of Ashrafi Devi, 60, as she points to the crevasse in the middle of her kitchen and the cracks that ruined the rest of her home. She has sent her children away to safety but will not leave the home she has known all her life. Nor can she afford to. “We spent every penny to build this house. My heart cries when I see this. It’s happening to all of us but no one has come to help.”

It’s a similar story across the state; where development projects have come, cracks have followed. The small village of Siwai, in the Chamoli district of Uttarakhand, has not stopped shaking for weeks as the mountains beneath are blasted for a new railway tunnel. Homes less than a year old now have cracks creeping up the walls, a devastating blow for this poverty-stricken community.

“They told us they wouldn’t do any blasting but now our houses shake violently every morning and every night, and they are going deeper and deeper beneath our homes,” says Sanjay Kumar, 29, whose house is now covered in cracks. His fear, echoed throughout the village, is that: “We are at the brink of becoming Joshimath.”

Lining the road on the way up to Joshimath are signs erected by the electricity department hailing ‘Hydro ki Laher Taraqqi ki Sahar (wave of hydro, a morning of progress).” But hydropower is now a dirty word in this town.

The Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower plant is being built by the National Thermal Power Corporation Limited (NTPC), a government public sector company, and has received multiple warnings since construction began in 2006. In 2014, a report commissioned by India’s supreme court explicitly recommended that no hydropower projects should go ahead in the high Himalayas as they risked further destabilising this young and unstable mountain range.

“Despite those clear-cut recommendations, the government made no change in its planning,” said Ravi Chopra, director of the People’s Science Institute in Uttarakhand, who headed the expert panel commissioned by the supreme court.

As disaster after disaster hit the NTPC hydropower project, concerns grew over the impact of the dam on the surrounding landscape, including nearby Joshimath. Construction involved blasting, drilling and boring deep into a known fault zone to excavate a 12km tunnel that would pass less than a mile from Joshimath, and residents reported regularly hearing the blasts.

It then emerged that rocks inside the tunnel were cracking unpredictably. In 2009, the construction machinery pierced a rock, and more than 700 litres per second of water gushed into the tunnel. Water continued to pour out for years after, and to this day the tunnel boring machine is stuck inside.

In 2011, a report by Austrian scientists called into question the accuracy of the ground surveys NTPC had done before embarking on the project and in a second report in 2015 they found the excavations were causing large-scale cracks and disruptions to water flows in the rock stretching far beyond the tunnel walls.

Then, in February 2021, a glacial lake burst high in the Himalayas, bringing a destructive and deadly torrent down the valley on to the Tapovan Vishnugad project, partially destroying it and filling the half-complete tunnel deep in the mountain with water, mud and debris. More than 200 people were killed in the disaster, and the tunnel is still filled with debris; several of the bodies of labourers who had been inside have still not been retrieved.

According to locals, just six month later, in October 2021, the first cracks began appearing in Joshimath, and subsidence – most often caused by the movement or removal of water beneath the ground – continued to accelerate.

The allegation now being investigated by independent geologists is that the cracks caused by boring and blasting the tunnel have spread deep into the mountain. As a result, the water that gushed into the tunnel after the 2021 disaster, and other disrupted water flows caused by construction, is now seeping through these cracks and destabilising the slope where Joshimath stands.

Suspicions were worsened when, on the night of 2 January this year, a new spring of muddied water erupted at the base of the Joshimath slope, with more than 500 litres of water per minute gushing out. The next day, the worst of the subsidence began in the town, triggering panic and eventual mass evacuations. District officials blamed bad drainage.

“We knew years ago that an invasive project like this can harm the town’s structure, harm water resources, harm agriculture, everything,” says Atul Sati, the convenor of the Joshimath Bachao Sangharsh Samiti (JBSS), the campaign group fighting for the town. “We raised the alarm as far back as 2000. In 2021, our worst fears were realised.

Navin Juyal, an independent geologist who is investigating the subsidence and has studied the area for 20 years, emphasises that all evidence against the hydropower project is currently circumstantial, but agrees that it poses a danger to Joshimath.

“While it is not possible right now to scientifically confirm the tunnel was responsible for what has happened in Joshimath, in the past the tunnel has led to cracks in the rocks and bursts of water they had not predicted,” he says.

NTPC is vehement in its denials, saying there is no correlation between its tunnel and the subsidence, pointing out that it is more than 1km from the town and that there has been no recent blasting. In the government’s own report into Joshimath’s subsidence in September, there was no mention of either government project – the NTPC dam or the Char Dham road construction – as a factor.

An expert panel set up by the government says it is now looking into all causes. Himanshu Khurana, a district magistrate of Chamoli district, denies that there was any attempt to cover up the role of any development projects in Joshimath. “Experts from the government of India and scientific institutions are on the ground, and they’re monitoring the situation and collecting research samples. We will have to wait for their opinion on this,” he says.

But Sati and others are sceptical that the truth will come out. “Big dams mean big money for the government – that’s why they support them,” says Sati.

Many fear the worst is yet to come. On 27 April, Badrinath temple will reopen to the public for the season, bringing with it up to 15,000 visitors a day. The road to the temple from Joshimath is already filled with holes from subsidence, which the administration has been rushing to fill in with gravel.

Residents are also dreading the notoriously relentless monsoon rains, fearful that their already unstable houses will simply wash away.

Experts say there is no way back from the subsidence, and people in the vulnerable areas will have to be removed, probably for many years. The government, however, has yet to give affected people definitive answers about their future, to the anger of many in the town who have been staging daily protests for more than 50 days, accusing the administration of obstructing the truth and failing to provide them with proper shelter and security.

Of the thousands of temporary homes that were promised, so far only 15 have been constructed.

“The government is trying to mislead the people by not telling the truth,” says Poonam Bisht, 40. “The whole country hails Narendra Modi, but we are heartbroken and homeless. He does not care or support us in this tragedy. He is silent.”

Peena Ben, sitting beside her, chips in. “The government put our lives at risk so they can continue with their big development projects, but what benefits are we seeing? They will only bother about us when we die.”

Additional reporting by Hriyadesh Joshi

Yahoo News

Yahoo News