SebastiAn: ‘Kanye West is what happens when you love yourself too much’

I was kind of delirious eight years ago,” the producer SebastiAn says. “The things I was feeling about politics, the ego... now it’s intensified. It’s even more difficult to understand.”

The French-Serbian artist born Sebastian Akchoté is discussing his new album, Thirst. It’s his first solo record since his 2011 debut Total but, contrary to many excitable headlines, it’s not some “grand return”. At least not to him: Akchoté is arguably most associated with the epochal French house label Ed Banger Records, and through it has released a regular stream of solo and collaborative work for the past 14 years.

Often in interviews, the 38-year-old is described as softly spoken and something of an enigma; I find him warm, energetic, quite boyish – especially when talking about his exploits with friend and fellow producer Kavinsky. He beams approvingly when a glass of wine is placed in front of me, though he’s not drinking at the moment, he says, adding the absurdly French: “I am living inside of the red wine.” He gestures all around him, as though our conversation were taking place in a giant bottle.

In fact, we’re sitting in a hotel bar in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, just round the corner from Akchoté’s studio, where he’s been rehearsing for a live set at Pitchfork festival. He turns an e-cigarette around in his hands while we talk about the new record. (“I used to smoke four packs a day,” he admits with a wince.)

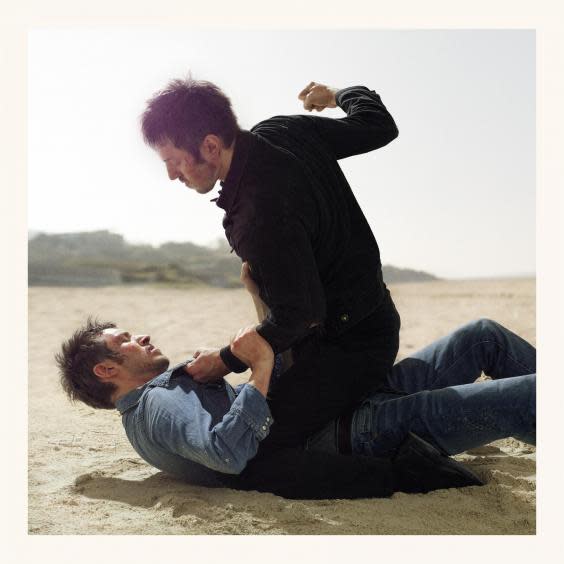

The cover art is by photographer Jean-Baptiste Mondino, who previously depicted the producer passionately kissing a version of himself for Total. Here, Akchoté straddles his stunned doppelganger and raises a clenched fist, ready to land a punch. He enjoys the fact that both images can be interpreted in myriad ways: Total was about ego, and the artist’s relationship with it. Thirst is more about the concept of progress: “We always sell the idea of progress as something cool, because it’s new,” he says, citing the philosopher Paul Virilio, “but it can also be a disaster.”

“Virilio spoke about how you’d have 2,000 people on a plane, and that was progress in a good way because you’re taking a lot of people from one point to the next,” he explains. “But then if the plane crashes, 2,000 people have died because of it. So yeah, progress can be both good and bad. And that’s what’s happening right now with social media.”

This interest in conflict, nuance and the idea of either/or as something limiting was the starting point for Thirst. From there, Akchoté set about collaborating with a disparate group of artists, from the renowned (Charlotte Gainsbourg, Mayer Hawthorne, Syd from The Internet) to the relatively obscure (Bakar, Loota).

“I didn’t know I was doing a new album at first,” he says. “I was just recording with some people I’d met. What was really important to me was.. you know, right now there are a lot of people who are making music by just exchanging files on the internet. For me, the important thing is to meet people, drink, have dinner with them. Getting to know the artist, creating stories. If you actually spend time with the people you work with, you can hear it in the music.”

Gainsbourg, whose 2017 album Rest was produced by Akchoté, recently lamented in a Guardian interview that everything is “so politically correct, so boring”, and that too many people are afraid to be brave in case they cause offence.

“Charlotte grew up with someone [her father, Serge] who had no limits,” Akchoté suggests. “I totally understand. Like, now, people are self-centred. Can you imagine doing what David Bowie did, pushing the boundaries of gender, today? This is what I call the craziness. And then you have someone like Kanye West, where it’s like months of hell, because he pushes himself too much. He reminds me a lot of the Total artwork, when you love yourself too much.”

“People have to choose,” he continues. “Do they want to have to think every five minutes about what they’ve just said, and whether they’ll be judged? You have all these small chapels – sexuality, politics, whatever – and you have to manage each one, because everyone is waiting to be angry.”

He believes that when Gainsbourg first approached him for her album, she wanted to create songs that were “more aggressive”. “It changed because her sister died,” he says, “and it wasn’t possible to do that anymore.” He remains proud of the album, which is a searing, almost merciless evocation of grief and the various forms it takes, but at the same time, “would prefer it not to exist”.

“It’s a strange thing to say,” he acknowledges. “But somebody died. It was all very intense. When you work with someone in this situation, you don’t just work with her; you work with her mother, and her husband, and her children. I learnt a lot, doing that album.”

In the US, Akchoté is arguably better known for his association with Frank Ocean, on whose album Blond he can be heard narrating “Facebook Story”, an account of how a former girlfriend assumed he was cheating because he hadn’t accepted her friend request. At the time, Akchoté was unaware the artist was recording him (Ocean had turned up to the London studio just as he was recalling the story). But by this point, he was used to Ocean’s unorthodox ways – he first reached out to him unexpectedly via Skype, and asked if Akchoté would fly out to LA. After five years of working together sporadically, Blond was released.

“I’ve never seen anybody like him,” Akchoté says. “I saw him building the Endless album and... he’s just strange, like a UFO.” They stay in touch, he says, in “a very Frank way”, in that the artist will call him out of the blue just to ask how he is, rather than to organise a new project.

Akchoté’s collaborative nature suits the Paris house and electronic scene, where artists such as Daft Punk, Justice and Mr Ozio team up or else remix one another’s work. His 2006 remix of Daft Punk’s “Human After All” is said to be the duo’s favourite take on one of their own songs, and prompted them to invite him and his labelmate Kavinsky on their Alive tour in 2007.

“I thought my career would last two years,” he jokes, “but then they called. I think they were both surprised because me and Kavinsky had never been to a club in our lives – we just listened to music at home or in bars. And then Kavinsky turned up for the tour with two bottles of red wine, which isn’t really a DJ kind of drink. But Kavinsky doesn’t give a s*** about anything – when he saw the pyramid for the first time he was like, ‘OK, Egyptian, cool.’ And they were like, ‘Who the f*** is this guy?’” he says, laughing.

As for the wider social and political landscape in France, Akchoté isn’t sure what’s going to happen – though he’s highly unconvinced by the concept of “Frexit” peddled by right-wing politician Marine Le Pen and her ilk. “I don’t think we’re going to get that far,” he says. “Our current president [Emmanuel Macron] kind of destroyed the concept of left and right.”

He returns to his notion of either/or in art. “You can’t have fun when there are only two possibilities. It’s just boring.”

Thirst is out now. SebastiAn performs with his Ed Banger labelmates at Electric Brixton on 31 January

Yahoo News

Yahoo News