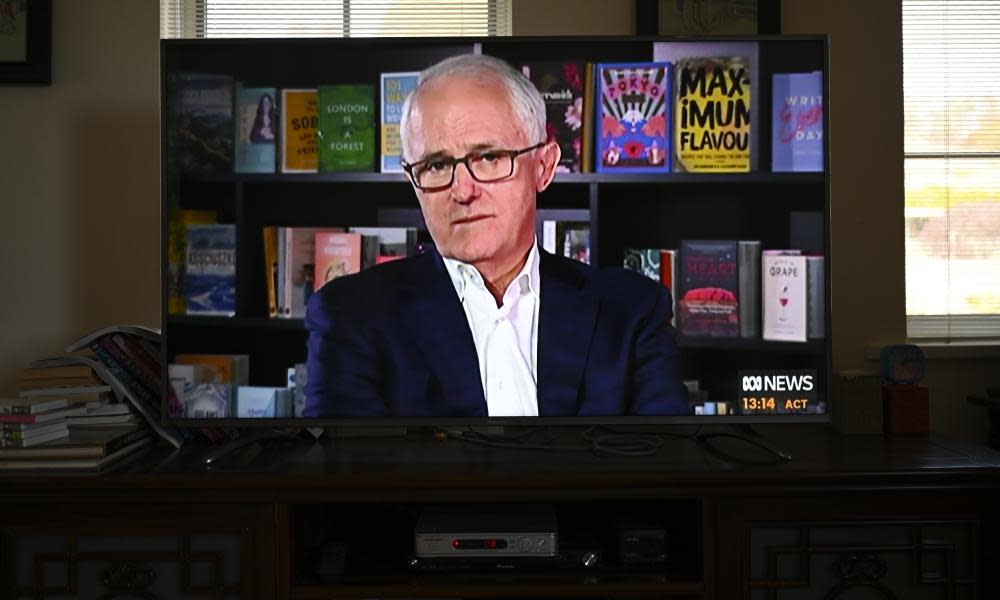

'Shameful': Turnbull rebukes Australian business for criticising China relations

Malcolm Turnbull has rebuked Australian business chiefs and academics for criticising the Australian government over the state of the relationship with Beijing, saying such reactions would only “encourage more bullying from China”.

The former prime minister said the response of some parts of the business community to China’s use of trade threats to influence policy was “pretty shameful” and said countries must “not be intimidated by confected outrage” from Beijing.

Related: Most Australians mistakenly think China is largest source of foreign investment, poll finds

Turnbull’s intervention comes amid ongoing trade tensions between the two countries, while Australia is also weighing up any potential responses to the Trump administration’s decision this week to harden its position against China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea.

A Department of Defence spokesperson told Guardian Australia that Australian defence force vessels and aircraft would “maintain our presence in the South China Sea and continue to exercise rights under international law, in accordance with our national interests”.

But asked whether the new US position could lead to a change in the frequency or nature of Australian operations in the region, the spokesperson said only that the ADF would not comment publicly on the details of future operations.

Turnbull said on Thursday that Australia must “defend our sovereignty with the same passion that China seeks to defend its sovereignty”.

Addressing a webinar hosted by the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies on the topic of China’s influence and activities in Australia, Turnbull said he did not believe that Beijing sought to change Australia’s system of government, “but what it seeks is compliance”.

“Ideally it would like an Australia that was moving away from the US alliance, but I think that’s probably a long-term goal,” said Turnbull, who was prime minister from 2015 to 2018.

“In the near term, their goal is to have an Australia that is compliant, that doesn’t complain about island-building in the South China Sea, that doesn’t complain about Uighurs being locked up in prison camps, that is generally quiescent – and the message you get consistently from China, both directly and publicly, is ‘stay out of this – it’s none of your business’.”

Turnbull noted that China was Australia’s biggest trading partner, with the export of commodities being a big part of the economic relationship.

Every now and then, he said, “when it suits them, they rattle the cage and threaten trade consequences”. This sometimes led to disruptions or delays to some Australian exports.

“The Australian business community, I have to say, to date has been invariably sensitive to this and tends to criticise the Australian government – it’s pretty shameful actually,” Turnbull said.

As an example, he referred to comments by the University of Sydney vice-chancellor, Michael Spence, who in 2018 accused the Turnbull government of “Sinophobic blatherings” and of not fostering a welcoming environment for Chinese students.

“We had to gently remind them and make a few points about, well, you know, essentially a little bit of patriotism wouldn’t have gone too far,” Turnbull said, without setting out other examples.

“The one thing the Australian business community and academic community have got to learn is that if you want to encourage more bullying from China continue behaving in the way they do, because every time they do that and criticise the Australian government over its China relations reflexively, Beijing says: ‘wow, gee that works, that’s terrific – let’s do a bit more of that.”

Turnbull said Australia needed to have confidence in the products and services that it sold “and not be bullied because it is, honestly, it is a slippery slope”.

He pointed to “the mess the UK’s got themselves in” over the potential role of Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei in the 5G network.

Related: Chinese media calls for 'pain' over UK Huawei ban as Trump claims credit

Boris Johnson’s government announced this week that Huawei would be stripped from Britain’s 5G phone networks by 2027 – reversing a previous decision to allow Huawei to supply 35% of the equipment – prompting Beijing to warn that the decision “must come at a cost”.

Turnbull said Australia had done a thorough assessment of the risks and made a decision in 2018, while the UK had been “going round and round on this issue and, of course, it’s become a political issue as opposed to a technical security issue and they’ve been subject to enormous pressure”.

Amid debate within many countries over how to handle relations with China, the US moved this week to toughen its position on China’s territorial and maritime claims in the South China Sea, specifically rejecting a range of Beijing’s claims.

Mike Pompeo, the US secretary of state, said the world would “not allow Beijing to treat the South China Sea as its maritime empire” and that the US would “stand with the international community in defence of freedom of the seas and respect for sovereignty” in the region.

When asked about the issue at a media conference on Thursday, Scott Morrison said Australia would “continue to adopt a very supportive position of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea”.

default

“We back that up with our own actions and our own initiatives and our own statements, but we’ll say it the Australian way, we’ll say it the way that’s in our interests to make those statements and we’ll continue to adopt a very consistent position,” the prime minister said.

Morrison said the issue was raised frequently in bilateral and multilateral talks and “it is one that Australia has taken a keen interest in but we’ve engaged respectfully and we’ve engaged proactively and we’ve engaged practically”.

China’s foreign affairs ministry accused the US of “muddying waters in the South China Sea, driving a wedge between China and regional countries, and undercutting the efforts by China and Asean nations to preserve peace and stability in the South China Sea”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News