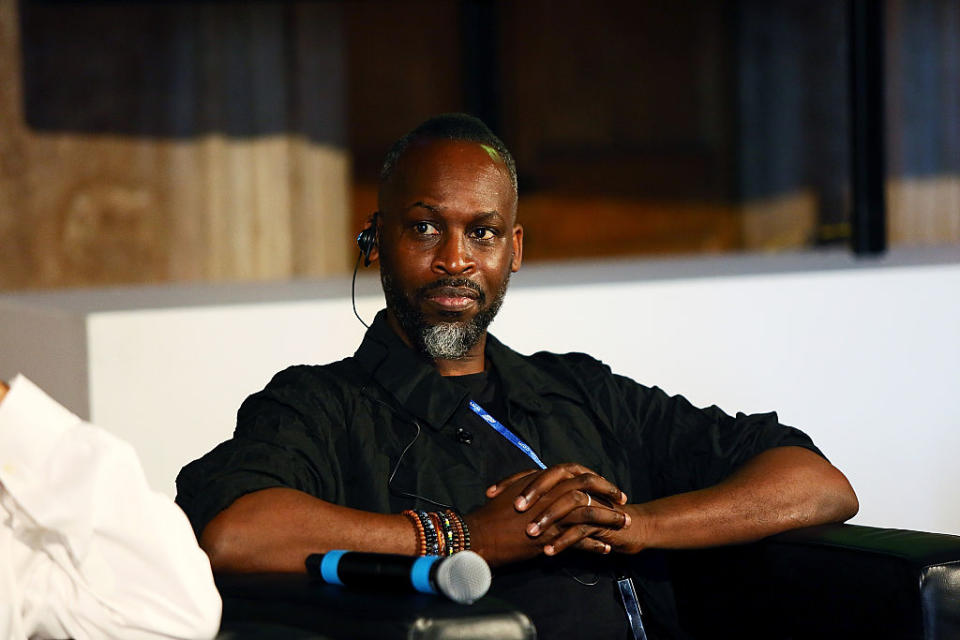

Simon Frederick on the rarity of black people in creative industries

As one of the Britain’s most highly regarded photographers and film-makers, Simon Frederick has shot everyone from Hollywood actor Forest Whitaker to ‘Line of Duty’ star Thandie Newton and The Archbishop of York, John Sentamu

His striking images have featured in magazines all over the world, he’s worked with many luxury brands and counts newly appointed Vogue editor Edward Enninful among his friends. His exhibition, Black is the New Black comprising 39 photographs of high-profile names from the worlds of celebrity, politics and culture (Sir Lenny Henry, Tinie Tempah and Chukka Umunna to name just three) will open at the National Portrait Gallery, London in the autumn of 2018.

But while he may be lauded, Simon is all too aware he is something of a rarity as a black man working in the creative industry.

‘It tells you everything you need to know when Naomi Campbell is sitting in front of me during an interview and says: ‘Wow, I can’t remember the last time I’ve worked with a black director,’ he says. ‘I’m always telling my mentees that black people can get into the creative industry but we have to work harder.

‘When we’re growing up, our parents constantly drum into us that we have to work twice as hard or we have to be twice as good to just get your foot in the door. To borrow an analogy, if you’re looking at the race of life as the Olympic 100m race, black people are at a starting line 50m behind everyone else and have to run further and faster just to keep up.’

The number of people working in creative industries who identify as coming from the black community makes up only 13 per cent of the workforce. Only eight per cent are in senior positions. As of 2016, there was only one black female in an executive position at an advertising or media agency in the UK.

The statistics come in the same week that it emerged nearly one in three Oxford colleges failed to admit a single black British A-level student in 2015, with the university accused of ‘social apartheid’ over its admissions policies by former education minister David Lammy. Similar data released by Cambridge revealed that six colleges there failed to admit any black British A-level students in the same year.

It’s why, at the end of this October (Black History Month) a collective from creative, advertising and communications and PR industries have teamed up to launch the STROBE event series which aims to tackle the lack of diversity in these areas.

Simon, who got his break in the early 2000s, says society is missing out by not encouraging more diversity within these industries.

‘When I was starting out, I had the skills but not the access to the top photographers’ agents and therefore the big creative and ad agencies in London that you need to in order to get that break into mainstream commercial photography,’ he says. ‘I remember going to nine creative directors with my portfolio and all of them told me that I’d never make it, that I was to forget it. It was the same for other really talented black photographers at the time. Some were doing sensational things with light and colour but their talent was simply ignored by those who pick and choose the next big thing. Without their endorsement there is no access and with no access there are no opportunities. This situation still prevails today. It’s the reason why many of us create our own paths.’

Yet Simon believes that breaking into these industries has as much to do with class as colour.

‘Unfortunately getting access to any branch of the creative industries means starting as an intern and usually those jobs are unpaid and can last for years,’ he says. ‘In an expensive city like London, unless you have parents who have deep pockets and can fund your ‘whim’ – or who grew up in the industry and understand that’s how it is (and that’s usually middle-class and white) – then if you’re not this, it’s difficult to get the opportunities.

‘Parents in working-class families think: ‘I want you to get a ‘good job’. Yet those ‘good jobs’ are still considered to be solicitor, banker or a doctor – jobs that will give you stability and you’ll be safe. As soon as you start choosing something your parents don’t understand, they are fearful that you will struggle.’

READ MORE:

Betty Campbell: Wales’s first black headteacher took civil rights history into classrooms

Black and ethnic minority teachers face ‘invisible glass ceiling’ in schools, report warns

Twitter creates Black History Month chatbot #ForTheCulture

He admits that he struggles himself with concepts such as Black History Month and terms like BAME (Black, Asian, and minority ethnic). ‘I think it’s ridiculous that we celebrate it,’ he says. ‘Our history as people of colour and white people are bound together whether we like it or not and we should be taught at school that we all have a common history that created this multi-racial society in which we now live.

‘My head aches when I hear the words ‘People in the BAME community have it so much harder.”

‘That’s true to an extent, however poor white kids have some of the same issues too, as do women, or the disabled and those from the LGBT community. The trouble is, all of these groups are lumped under the same term ‘diversity.’ We’re all talking over each other to get our voices heard when the rich, white, powerful men at the top are laughing.’

Simon hopes for the day when jobs will be taken on merit alone. He recalls what former ITN news anchor Sir Trevor McDonald told him during an interview for Black is the New Black.

‘When Sir Trevor came to the UK, he was already a successful journalist over in Trinidad and simply wanted to further his career,’ says Simon. ‘His editor was so impressed that he asked him to present the news and Sir Trevor told me he was really shocked by that. Having a black man presenting the news on a British commercial station in those days was considered a really brave move. But the fact was, he was simply good at what he did.’

Do the recent appointments of Edward Enninful as editor of Vogue and Vanessa Kingori as publisher signal progress?

‘Things are changing for the better,’ admits Simon. ‘Those top jobs going to Edward and Vanessa shows a definite sea-change. People always said there would never be a Vogue Africa because they could not see the vision for any demand but that may all change now. And that’s wonderful. But it’s only one company.

’You look around the offices of many other institutions and they are still very much middle-class, very white institutions,’ he says. ‘I don’t believe that’s because people are intrinsically racist, they are naïve. They simply don’t come into contact with people from an ethnic minority in a social context. They live in an ‘ethnic-free bubble’, where they may well encounter people of colour on television or in magazines or driving the bus but they don’t meet them in their own world. This needs to change because if you have different types of people within an organisation, you get different types of thinking and new ways to solve problems. That’s something that this country could really do with that right now.’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News