Simon Rattle: ‘What you can do in your 50s you can just about do in your 60s, but not in your 70s’

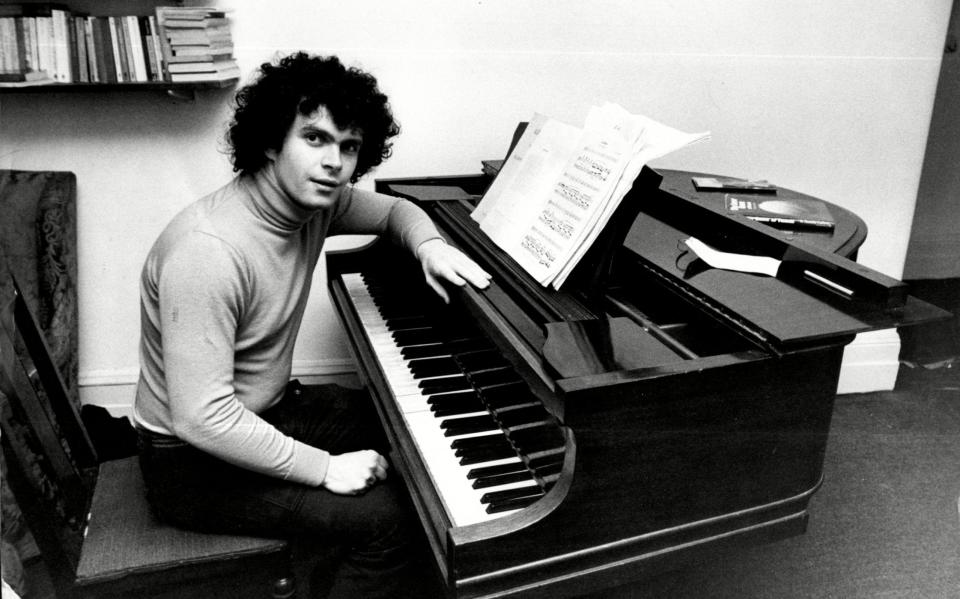

For decades Britain’s best-known conductor, Simon Rattle, could not shake off the role assigned to him when he first burst onto the musical scene in the 1970s: the talented, tousle-haired youngster with a determination to do things differently, who everyone believed would one day be a contender for the title of “world’s greatest conductor”. Well, they were right. Sir Simon (the “Sir” came in 1994) has been at the top of his game for decades, having been principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 16 years and music director of the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) since 2017.

While the demands of an industry laid low by the pandemic still loom large for him (more of which later), when he joins me on Zoom from his home in Berlin he’s preoccupied with a more pressing problem – one that doesn’t affect many conductors at his stage of life (he’s 66). His seven-year-old daughter – the youngest of the three children he’s had with his second wife, the Czech mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená – threw a tantrum before our call, and had to be soothed.

“My children need me now, not in 10 years,” he says, “and Munich is only a train ride away from the family home in Berlin. It really is that simple.” He is talking about his departure next autumn from the helm of the LSO to head the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. While family life is one reason for the move, I suggest his heavy touring schedule could also play a part.

“I’ve come to realise that what you can do in your fifties you can just about do in your sixties, but not in your seventies. It’s truly astonishing the way this bunch of musicians can have a grisly day of travelling, turning up at Stansted airport at 6am, and still play a fabulous concert in the evening. But it takes its toll. I mean there is a reason why people retire in their mid-sixties.”

It’s easy to think that the orchestral world is now back to normal and can put the agonies of the pandemic behind it, but Rattle still feels a cold fury at the way musicians were treated by the Government during the pandemic, with most freelance orchestral players receiving no support and music venues being among the last public spaces to be released from lockdown restrictions.

“For the musicians of the LSO, it’s very simple – if you don’t play, you don’t get paid, and it was so tough for them. They were the first to be told to stop work, and the last to be allowed to go back to work. So they know their place in the Government’s priorities. I remember being called to a meeting with Oliver Dowden [just before the Culture Recovery Fund announcement in July 2020] where he said very clearly that the great thing about the arts in Britain is that they are not supported by the state in the same way, so they end up being much more self-reliant, and are much better for it. I was horrified when I heard that. Dowden denied it later. I would be less angry if he could be straight and say, 'Yes, this is what we believe.'”

Being such a prominent campaigner for the arts as well as a leading conductor, Rattle is used to being asked awkward questions about cultural politics. But he sighs when I ask him whether he thinks the Last Night of the Proms should be banned, or at least reformed. He has never conducted it and, in the past, has said he felt uneasy about its “jingoistic” elements. Now, he asks wearily: “Am I allowed to give you a nuanced answer? It’s so difficult to talk about this topic. I would fight for anyone’s right to enjoy the kind of music they want, and the Proms is certainly popular.

“There’s something wonderful about sharing a song, and the Proms is one of the few occasions where many people can do that together. So I think it would be a bad thing to take it away from people. It’s a great way to close this astonishing music festival, though it’s not something I particularly want to conduct myself.”

Of course, UK audiences have only one more season to enjoy Rattle’s dynamic presence on the podium. What have been his priorities in putting together this final season? “The pleasure principle,” he says simply. “There are so many things we’ve wanted to do these past two years, but the pandemic made it impossible. Big, ambitious things like the Brahms Requiem and Szymanowski’s Stabat Mater, two of the strangest and most wonderful religious works ever composed.

“We’re doing a complete performance of Janáček’s opera Katya Kabanova, and eventually we aim to perform and record all of Janáček’s operas.”

The most spectacular of these big-scale concerts takes place next week when the LSO will be joined by musicians from the Guildhall School of Music and the Music Academy of the West, in Santa Barbara, for a concert in St Paul’s Cathedral. It’s a venue that Rattle has never conducted in before.

“It’s a fabulous space, it gives me goosebumps every time I walk in,” he says. “But there’s no getting away from the fact that the huge echo can do very strange things to orchestral music. So you have to choose the music very carefully.” The two centrepieces of the concert are Messiaen’s Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum, a piece of apocalyptic grandeur for wind, brass and percussion which the composer said should be played on a mountaintop or a cathedral, and Berlioz’s stupendous Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale.

“I’ve done a sort of arrangement of the first movement of Berlioz’s piece, which I think is a real masterpiece, so we can do it as a procession going into the cathedral,” says Rattle. “Apparently, at the first performance, this huge orchestra processed into Les Invalides, in Paris, with Berlioz conducting with a sword while walking backwards. Can you imagine? It’s one of those stories you so want to be true.”

As for the bigger and even more pressing issue of “diversifying” classical music, Rattle welcomes it and has put his money where his mouth is with his final season. “From the point of view of musical quality, we’ve simply been missing a trick. We’ve been playing music by black American composer George Walker. And we’ve been looking further afield when we commission new pieces. There’ll be a new piece from Betsy Jolas, who is an incredibly youthful 95, and Daniel Kidane, the black British composer. It’s all a sign of a swing of the cultural pendulum, which had to happen. And we should embrace it.”

Sir Simon Rattle conducts the LSO at St Paul’s Cathedral on June 23. Tickets: lso.org.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News