Simone Rocha: Esprit de Corps

Who is Louise Bourgeois?

Her tiny frame (she barely reached five foot) housed a giantess of modern art, that much is certain. Yet this French-American creative powerhouse, who died 10 years ago aged 98, embodied a host of other, often opposing, identities: damaged Chanel-wearing little girl; cautiously doting wife; feminist icon; hermit; provocateur; victim; tyrant; and, of course, ‘spider woman’. But although her monumental arachnids may have brought Bourgeois as close to being a household name as her iconoclastic brand of avant-garde art ever could be, she was in fact a prolific multimedia master, producing reams of installations, prints, writings, drawings and hand-woven fabrics.

Born in Paris on Christmas Day in 1911 to a family of tapestry-dealers, Bourgeois endured a difficult childhood, tainted by anguish caused by her unreliable father, who had a 10-year affair with her governess, and agonising sympathy for her beloved mother, who submitted silently to the infidelity. After swapping the study of mathematics for art at the Sorbonne, Bourgeois married the art historianRobert Goldwater and moved with him to New York in 1938, where they had three sons. She made art, practically unnoticed, until the age of 70, during which time she explored the most profound aspects of humanity: fragility, gender, sex, nature, pain, motherhood, time, insomnia, memory... In each case, she translated her fears and enthusiasms into creative production, saving her sanity, agitated as it was by her troubled youth and struggle to find a peaceful place in the world.

Eventually, in her eighth decade, she was discovered by the art market. She became the first woman to have a retrospective at MoMA in 1982, opened the new Tate Modern with a site-specific commission in 2000 and went on to become one of the world’s most important contemporary artists – last year, her 1996 Spider was snapped up for £25 million, making it the most expensive sculpture ever produced by a woman.

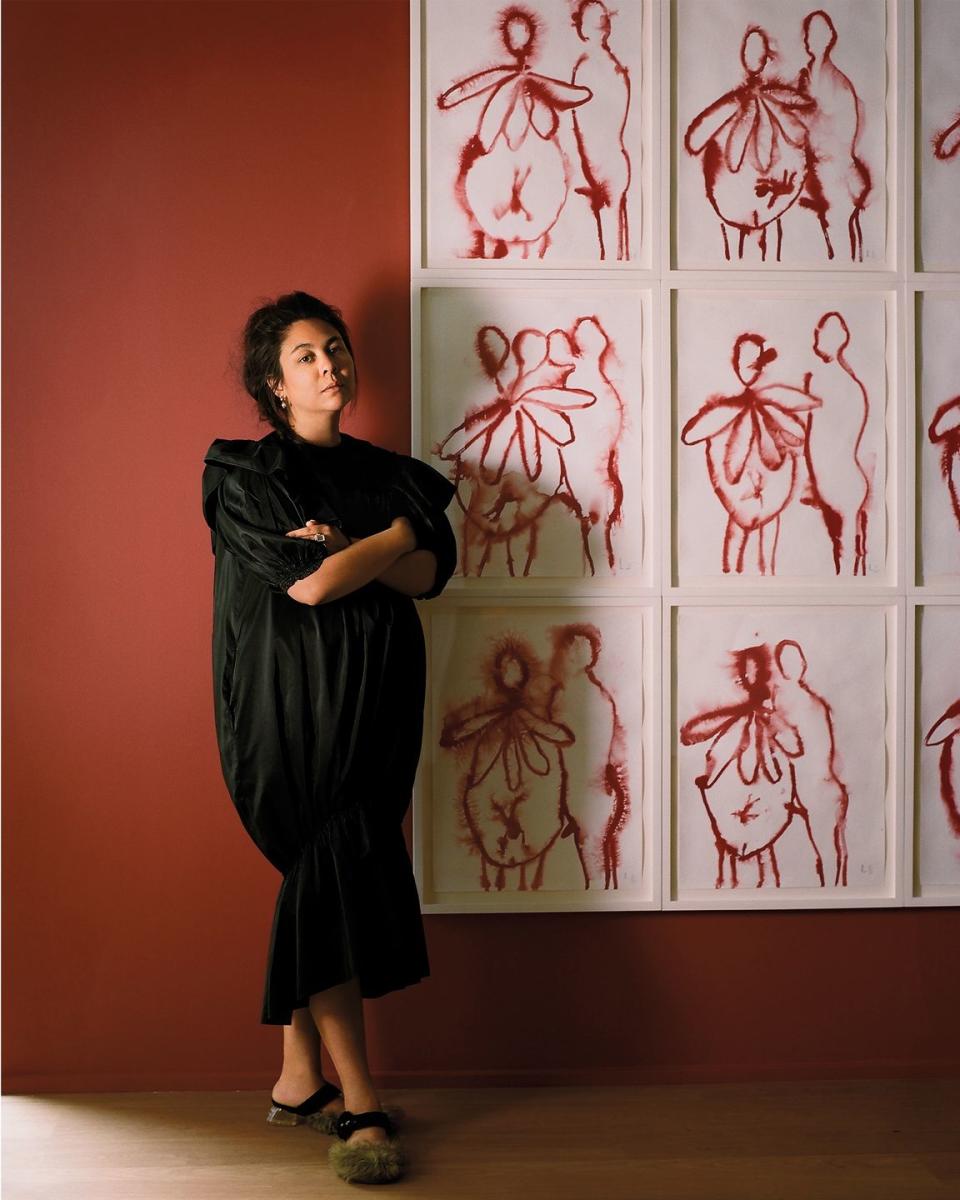

Bourgeois has been a muse to many luminaries in the art world and beyond, including the British fashion designer Simone Rocha, who founded her eponymous womenswear label in

the year of her artist heroine’s death.

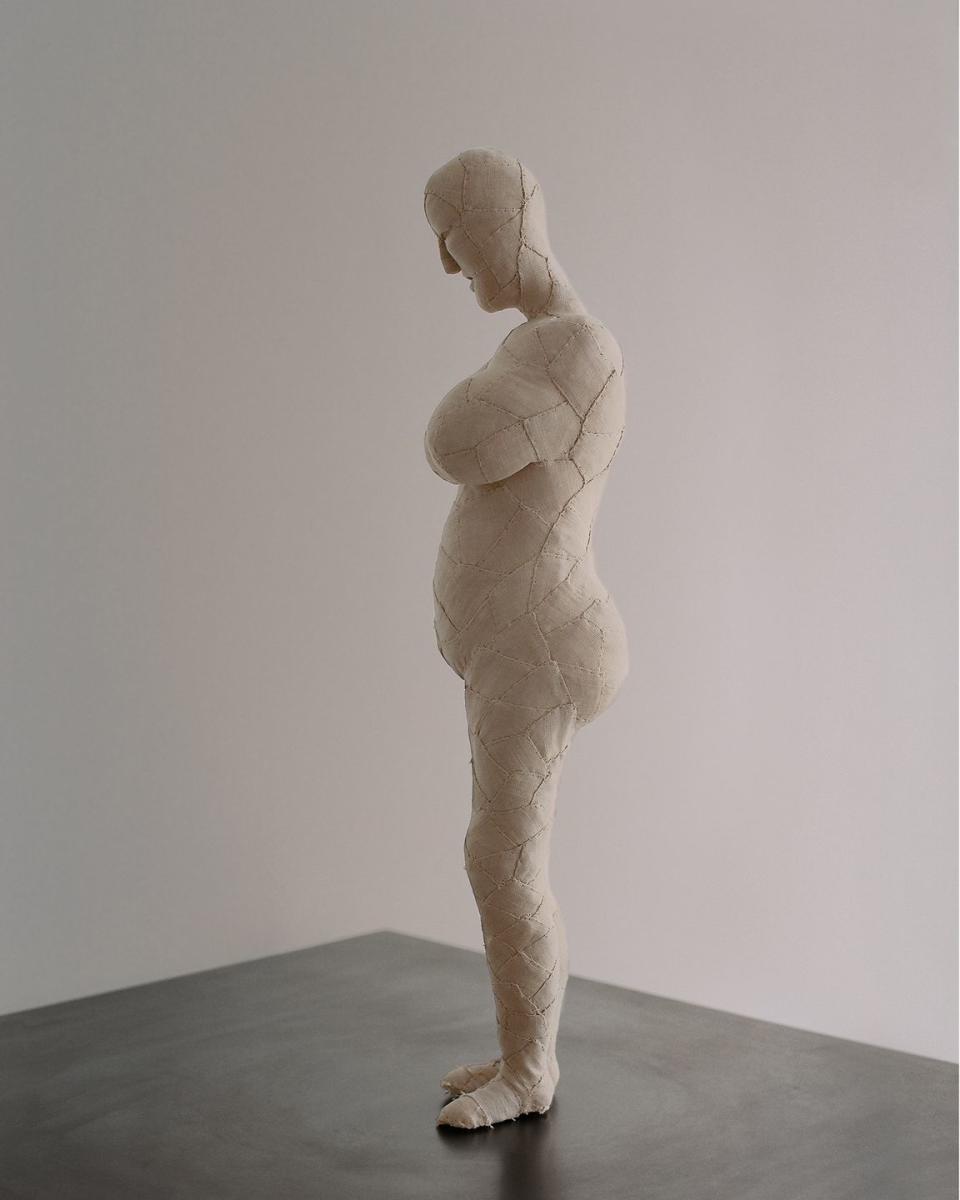

When I talk to Rocha over Zoom, she speaks passionately about the day she first saw Bourgeois’s work as a teenager at Dublin’s Irish Museum of Modern Art, in a solo exhibition called ‘Stitches in Time’, focusing on her fabric figures. "There was a series

of bodies, hanging in mid-air, quite disturbing,’ she remembers. ‘And yet, they were so tenderly stitched from this soft, domestic terrycloth, pink fabrics. They blew me away." The

pleasure of the paradox between the macabre mood and the use of classically feminine hues and hand-sewn textiles enchanted the designer in 2003; today, having devoted her student thesis to the artist, visited her former home, and filled her studio with books by and about her, Rocha makes Bourgeois’s influence manifest in almost every garment she creates.

The dialogue between oppositions at the heart of Bourgeois’s work (‘Expose a contradiction, that is all you need,’ the artist once said) draws Rocha back to it time and again. "Contrast is so stimulating. Even when they’re grotesque, Louise’s works always contain something soft in them, and vice versa," she says. "I use a lot of tulle, gossamer laces and delicate fabrics, so to ground them, I’ll put a very practical, heavy shoe at the bottom. That tension between fantasy and hard realism is what I want my clothes to balance on." HerA/W 19 collection, designed in collaboration with the artist’s archive, made direct references to Bourgeois’s work, reimagining her fibreglass phalluses as voluminous ruched puffs of satin and converting her famous cobweb patterns into a gingham-style print used on a beautiful taffeta dress-coat. Resonating throughout the collection were those conceptual collisions between the grotesque and the sublime, the physical and the psychological, joy and difficulty.

The designer has also been influenced by Bourgeois’s inventive reinterpretation of the notion of femininity. Maman (1999), Bourgeois’s vast spider homage to her mother, is monstrous enough to give anyone arachnophobia, yet there is a delicate fragility to its spindly legs and a certain cosseting comfort to be found from standing beneath its vast form. This daunting character has a nurturing aspect as well. "I come from a family of repairers," Bourgeois once stated. "The spider is a repairer. If you bash into the web of the spider, she doesn’t get mad. She weaves and repairs it." Rocha can relate to this, having also been born into a family whose prosperity stems from sewing. Her father is the celebrated fashion designer John Rocha, whose brand is managed by her highly stylish mother Odette – a treasured source of inspiration and the origin of her introduction to Bourgeois’s work.

Maternal inheritance, particularly a passing on of the positive power of stitching, is a constant thread running through Bourgeois’s life and legacy. The art collector Ursula Hauser, who says the most important moment in her career was visiting Bourgeois’s studio, shared her passion for the artist with her daughter Manuela, whose gallery Hauser & Wirth now represents Bourgeois’s estate. "Like my mother and Simone, I have a very deep relationship with fabrics and handicraft; I am a strong believer that working with textiles and wool is therapeutic," says Manuela. "I’m drawn to both the tactile qualities of Louise’s work and the deft way she layers themes of motherhood, healing, relationships." She finds Bourgeois’s terry-cloth figures the most moving, for their brutal-looking gentleness.

Indeed, perhaps Bourgeois’s elevation of stitching from domestic activity to fine art is one of her greatest breakthroughs, paving the way for our current era, when the line between fashion and art is increasingly blurred. For her, the needle became a tool for profound personal rehabilitation. "I always had the fear of being separated and abandoned. The sewing is my attempt to keep things together and make things whole," she wrote.

Rocha, too, loves the notion that interweaving thousands off ragile threads creates something entirely new that is stronger than the sum of its parts. Her label’s clothes often present a game of hide and seek between the wearer and the onlooker: high-neck ruffs dis-tract from a flash of thigh at the side; a slinky mini-dress is made overall-like when styled over brown suit trousers and brogues."There’s a power in that revealing and concealing, even if it’s just the slightest bit of skin or self," Rocha reflects.

Small wonder that she is deeply influenced by Bourgeois’s observation that "clothes are as much about what you want to hide of the body as what you want to expose. This is a form of communication." The idea of garments being both a shield for and window to one’s soul is perfectly illustrated in the artist’s painting Blue Dress (1998), in which the subject’s bones are visible, X-ray style, through her frock.

Bourgeois was fearless in exploring bodies, sex and her emotions towards them in her work: anatomy in all its messy and magnificent glory abounds. Likewise emboldened, Rocha subtly builds biomorphic forms into her clothes, bringing graphic physicality to the elegant environs of London’s fashion weeks: at her first show after giving birth, she recalls sending placenta-inspired earrings down the catwalk.

"They were blood-red, bejewelled and drippy!" she says. "My daughter is the light of my life, yet it was also horrific, so I needed to communicate that." Turning a visceral personal experience into something resplendent, gothic and ever so slightly gory seems textbook Bourgeois – and it echoes The Family I (2007), the painted depictions of man, woman and abstract embryo with which Rocha is photographed here, in both subject matter and sanguine execution.

Despite the intimate, serious stories that Rocha and Bourgeois tell in their work, both seem to have an appetite for amusement. The designer gleefully recalls the reaction in some quarters to her post-partum creations: "Even people I’m really friendly with were like, ugh, seriously, a vagina collection? Do you have to put us through that?" Equally, it is perhaps Bourgeois’s unpredictable sense of humour that rescues her self-referential spirit and work from being off-puttingly narcissistic. Her friend and assistant of 30 years, Jerry Gorovoy, recalls her propensity to splice shade with light vividly. "There were ups and downs," he tells me. "Fits of rage, and beautiful moments of laughter." Think, too, of the black comedy of the artist fashioning figures of her father out of bread before gobbling them up, which inspired The Destruction of the Father (1974). Her mischievous grin and twinkling eyes are evident in so many photograph portraits, whether she is cradling a large latex penis like a baby (Robert Mapplethorpe, 1982) or posing in a little crown (Bruce Weber, 1997).

This impishness seems to be part of whyBourgeois often refused to spell out the meaning of her sculptures, or indeed to give interviews, saying that a work of art does not require an explanation. Staying enigmatic –steering clear of art historians and their theories, critics and their cod psychology, journalists and their headline-making epithets – gave her creative space. As she put it, "inspiration comes from retreat". Rocha thinks similarly: she rarely provides mood-boards that dissect her vision and process, preferring people to react intuitively. "Once you start labelling your-self or your craft, you lose some freedom," she reflects.

Perhaps in today’s world of social media, confessional art and self-exposure, we could learn something from this star artist’s desire to remain ambiguous. Being unknowable, and perpetuating a self-contradicting legend, is frustrating for theorists, but has its merits– and guarantees eternal intrigue. We will never know whether whatBourgeois said about how being an artist insures one against becoming a murderer was a joke or for real. As Germaine Greer wrote days after the artist’s death: "Bourgeois will continue to mock all certainty, not least certainty about the artist herself." You can’t help but think she might be right.

In need of some at-home inspiration? Sign up to our free weekly newsletter for skincare and self-care, the latest cultural hits to read and download, and the little luxuries that make staying in so much more satisfying.

Plus, sign up here to get Harper’s Bazaar magazine delivered straight to your door.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News