As the Skripal theories abound, I'm reminded of when I visited Iraq at the time of the dodgy dossier

Boris Johnson declares that “there is something in the smug, sarcastic response that we’ve heard from the Russians that indicate their fundamental guilt.” Gavin Williamson’s considered response to the crisis is that Russia “should go away and shut up”.

There is, of course, more than Boris’s cunning deductions from Kremlin sarcasm and Williamson’s marching order to Vladimir Putin – surely one of the most unintentionally comic turns in modern political times – behind Theresa May’s assertion that Moscow has carried out an attack with a nerve agent for the first time in Europe since the Second World War. By this afternoon, the Foreign Secretary was holding that it was “overwhelmingly likely” that the Russian President had personally ordered the attempted murder.

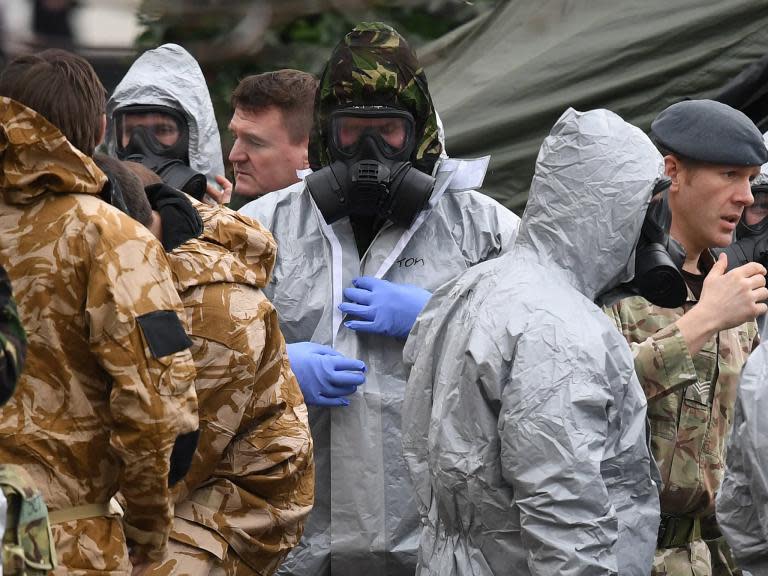

The British Government came to the conclusion of Kremlin culpability very early after the poisoning of former MI6 agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia on 4 March. There had been criticism of the slowness of the police investigation into the attack on Alexander Litvinenko, who was contaminated with polonium also allegedly by the Russians, and on this occasion the inquiry has moved at remarkable pace.

There has been scepticism about the intelligence services, with much publicity in the case of Seumas Milne, Jeremy Corbyn’s spokesman, who likened its conclusions about Russian collusion to the false claims about Saddam Hussein’s Weapons of Mass Destruction used to justify the invasion of Iraq. “Obviously the Government has access to information and intelligence on this matter which others don’t”, said Milne. “However, also, there’s a history in relation to weapons of mass destruction and intelligence which is problematic, to put it mildly.”

There are points of issue here.

The same intelligence assessment on which the Government and the National Security Council made their decision to blame Russia was shown to Corbyn as a privy councillor, we are told by Whitehall officials. He, presumably, was not convinced by what he saw. Secondly, there is an obvious difference between the alleged WMD in Iraq and the Salisbury attack. WMD did not exist in Iraq at the time of the invasion, whereas we know that a nerve agent was used on the Skripals – unless Milne holds that was concocted.

Intelligence was manipulated, “sexed up”, on Iraq to provide George W Bush and Tony Blair the justification for a war they had already decided on waging. It is unclear who exactly wants to restart the Cold War in the West. It is hardly likely to be Donald Trump, under investigation for being the alleged Muscovite candidate in the US election. There’s no clear reason why Germany, France or the UK would want to do so either.

There is, however, a common factor between what happened in Iraq and the current crisis: a tendency to attack those who question the official version of events, with accusations of being unpatriotic, a traitor, even – something Jeremy Corbyn is facing. The Leader of the Opposition may well have “misjudged the mood of the House” on Wednesday, but the questions he raised had validity.

It is impossible to judge the intelligence performance on the Salisbury attack at this time because we simply do not know the details of why the services are convinced that the Russian state was behind the attack. There was more scope to examine the Iraq intelligence even before the extent of the secrets and lies came out in the various public inquiries which followed.

I was among a small number of journalists in Iraq before the invasion accompanying the UN teams searching for the supposed arsenal of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons. On visits back to England and the US, it was apparent that the inspections, meant to be the key to resolving the crisis, were just a sideshow. While paying lip service to the UN, the Bush and Blair administrations were preparing for war.

In September 2002, a few colleagues and I downloaded from the internet, at the Al Rashid Hotel in Baghdad, the Downing Street dossier on the “imminent threat” posed by Iraq’s WMD. We had arranged with Tariq Aziz, Iraq’s deputy prime minister and Saddam confidant, to visit some of the sites named in the dossier as producing chemical and biological weapons. We chose the sites – al-Qa’qa, a military complex 30 miles from Baghdad and the Amariyah Sera vaccine plant at Abu Ghraib – and were taken there by the Iraqi authorities within two hours of the dossier being produced.

We were allowed to go anywhere we wanted at the sites and to take soil samples. But we were scrupulously careful in the stories we filed to stress that we were not scientists or weapons experts and so could not make judgments about the facilities we had visited.

The reaction of the Downing Street spin doctors was ludicrously over-the-top. The accusations against us ranged from being “naive dupes” to “propagandists for the Saddam regime”. After “liberation”, the two sites we had been to and every other named in the dossier were inspected by UN teams and the Iraq Survey Group set by the US and UK. No WMD, of course, were found.

Details of what led the intelligence services to conclude that the Kremlin carried out the Salisbury attack will emerge, no doubt, over time. The reason why it is surprising has been well rehearsed. Litvinenko had been an active campaigner against the Kremlin and Putin in his London exile and this may have raised their ire. There is no evidence of this with Skripal.

The former Russian military intelligence colonel had been in prison in Russia for more than a dozen years; he could have been bumped off any time if they really wanted to take retribution on traitors. Skripal had come to Britain in a spy-swap and was no longer active. The fact that he lived under his own name, and had not been given a false identity, was clear indication that he was not deemed to be in danger.

There has also been a wide range of theories, some masquerading as facts, in the media about what supposedly happened – that Skripal was working on the Trump dossier; that his daughter was the real target of the attack because of her love life; that the nerve agent had been administered through the door handle of his car; or in his food; or that it had been slipped in through a present his daughter had brought from Moscow.

There was also a claim that he remained a MI6 agent and had been meeting his handler in Salisbury. The two men did not bother with things like security precautions, it seems, but met in the same restaurant every month and spoke loudly in Russian. Waitress Dagmara Wieczorak told a tabloid that she was “sure” that she was shown a picture of an “Englishman in a tweed suit that used to meet Sergei every month”. Asked about this, a security official responded tiredly, “Yes, being MI6, not only was he wearing a tweed suit, but he also carried a pipe, wore a carnation and they greeted each other with the code ‘It gets very cold in Vladivostok’.”

But real facts are sparse on the ground. A crime as elaborately planned as this surely needs a motive, so what was it? If Russia “lost control” of the nerve agent, the alternative charge by Theresa May to the attempted assassination, when could this have happened? Why did the director general of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OCPW) categorically state last November that all chemical weapons in Russia’s stockpile have been destroyed?

The Kremlin may well be responsible for the Salisbury attack as May’s Government insists. But questions need to be asked, including by politicians, and answers should be provided rather than hysterical accusations of treachery.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News