The SNP lost tens of thousands of members under Nicola Sturgeon – here's why that should worry her successor

All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition of life and his relations with his kind.

So wrote Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto. They were talking about how what had previously been taken for granted could be swept away by capitalism. But they might as well have been talking about the way the contest for the leadership of the Scottish National Party has upended all our assumptions about that party – not least, that it was exceptionally united and had an impressively large and loyal rank-and-file membership.

That’s because, following Nicola Sturgeon’s shock resignation, the party has rapidly succumbed to the kind of bitter ideological infighting between ambitious rivals that many of us had begun to associate almost exclusively with the Conservative Party south of the border.

And not only that: in the course of the contest, the party has been forced, under pressure, to admit that it has nowhere near as many members as the rest of us had assumed – an admission that prompted the resignation of the SNP’s embattled chief-executive, Sturgeon’s husband Peter Murrell.

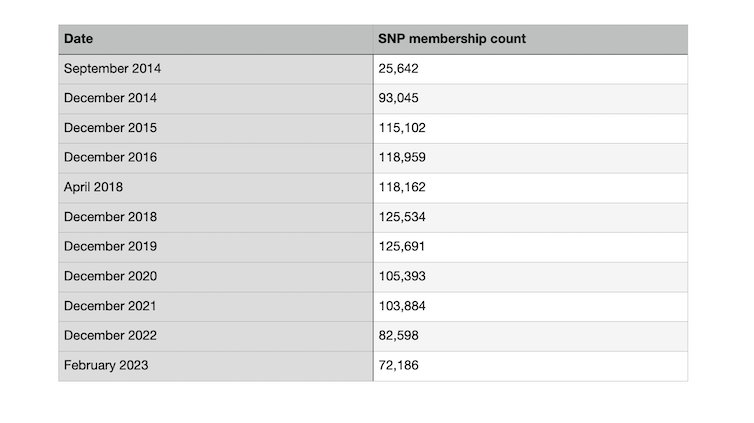

Quite why the latest figure of 72,186 members had to be dragged out of party HQ is, for the moment at least, anyone’s guess. But what is certain is that it constitutes a marked drop on the 100,000-plus that was widely quoted before this latest number was reluctantly released.

And it seems equally certain that we are seeing the end of a truly phenomenal period of grassroots growth for the Scottish nationalists which began after (and probably during) the 2014 independence referendum.

The SNP, of course, isn’t the only party in the UK to have experienced something of a membership growth spurt during the last decade. Lots more people were prompted to join the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn. And, although it escaped most people’s notice, the Liberal Democrats attracted a lot of new members when they returned to opposition after five pretty brutal years in coalition with the Conservatives between 2010 and 2015. Meanwhile, the Tories themselves issued just over 172,000 ballots to members in the summer 2022 leadership contest won by Liz Truss, compared with the 159,000 or so it had issued in 2019 when Boris Johnson replaced Theresa May.

Reasons for leaving

The question of why people join political parties has preoccupied academic observers since the pioneering survey research carried out by academics Patrick Seyd and Paul Whiteley in the late 1980s – a tradition built on more recently on by the Party Members Project run out of Queen Mary University of London and the University of Sussex.

What we’ve tended to pay far less attention to, however, is why members leave. This is the issue that should now be worrying the SNP, assuming that, like most political parties, it welcomes not just the legitimacy a thriving membership confers on its cause, but also the money and manpower members contribute.

That doesn’t mean that there’s been no research into this question. It is one we tried to answer in our book Footsoldiers: Political Party Membership in the 21st Century, and which we followed up more recently after Keir Starmer replaced Corbyn in 2020 – a development that caused much soul-searching last summer when the party was reported to have lost tens of thousands of members.

Although parties often fret (not without reason) about administrative failings or the cost of membership or even boring or conflictual meetings driving members away, our surveys of people who’ve quit parties show that none of these matter that much.

Instead, what prompts people to let their membership lapse or, more dramatically, to leave in high dudgeon is a sense that the party is going in the wrong direction, or adopting a particular policy or policies that they disagree with.

Our research also shows that this ideologically-motivated distancing and detachment is often bound up with dissatisfaction or plain disagreement with the leader of the party – whether that be the incumbent or their successor.

What is particularly interesting in this regard is that the SNP’s recent loss of members occurred on Nicola Sturgeon’s watch, not as a result of her resigning. This suggests that, for whatever reason, a fair few people had become disillusioned with her leadership and the direction in which the party was going.

Unfortunately for the SNP, it seems fairly likely – especially given the bitterness engendered by the contest to replace her – that whoever takes over from Sturgeon may well end up presiding over further losses, as those disappointed with the result quit too.

If that does happen, then we should also monitor what happens to membership of the Labour and Green parties north of the border, as well as of the alternative nationalist party, Alba. That’s because one thing we also know from our research is that a surprising number of people actually leave their party in order to join another one. So watch this space.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tim Bale's research for the Party Members Project was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Yahoo News

Yahoo News