Sonny Barger and the Hells Angels: Five Ways the Outlaw Motorcycle Club Left Tire Tracks on Pop Culture

With the death this week of Ralph “Sonny” Barger, national president of famed motorcycle club the Hells Angels, a piece of vibrant American pop culture history recedes farther into the past.

It’s hard to appreciate today, but when Barger founded the Oakland chapter in 1957, the mythology of the outlaw biker had already been emblazoned on the national consciousness through the Hells Angels’ impact on fashion, movies and music, as a symbol of rebellion. Barger’s death on June 29 at the age of 83 made international headlines because of that reach.

Barger was the face of the Hells Angels for decades, but the origin story of the Hells Angels began nearly a decade before when the club was founded in Fontana, Calif., in 1948. The mythos of the rebel clad in black leather astride their prized “hogs,” as their often-chopped Harley-Davidson motorcycles are known, is now entrenched in the public’s imagination. That legacy lives on every time a radio station or streamer plays Steppenwolf’s counterculture anthem “Born to Be Wild” and in every unspooling of landmark movies like 1969’s “Easy Rider” and the Maysles brothers’ 1970 concert film “Gimme Shelter.”

Here’s a look at five ways the Hells Angels and its longtime leader left tire tracks on on pop culture.

Hunter S. Thompson

“Hells Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs” was the book that launched the career of legendary journalist and novelist Hunter S. Thompson, of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” and “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail” fame. Published by Random House in 1967, “Hell’s Angels” began as “The Motorcycle Gangs: Losers and Outsiders” for the May 17, 1965, issue of The Nation magazine. But more than just his first national exposure as a writer of importance, “Hell’s Angels” had a profound effect on Thompson, who blazed his own trail in what he described as the ethos of Gonzo journalism. Thompson maintained that unpredictable, wild man persona until his death in 2005, after which actor Johnny Depp (who played Thompson on screen in the 1998 adaptation of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” paid the cost of having Thompson’s ashes shot out of a cannon on Thompson’s beloved ranch in Woody Creek, Colo.

In a contemporary New York Times review of the book, Thompson related how he “drank at their bars, exchanged home visits, recorded their brutalities, viewed their sexual caprices, became converted to their motorcycle mystique, and was so intrigued, as he puts it, that ‘I was no longer sure whether I was doing research on the Hell’s Angels or being slowly absorbed by them.’ ”

Scorpio Rising

The impact of Kenneth Anger’s groundbreaking 1963 experimental film “Scorpio Rising” is driven by the film’s exhilarating employment of pop music hits, which makes it a major influence on key 1970s filmmakers such as Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas and Martin Scorsese. But there’s also a creepy off-kilter quality to Anger’s study of a Hells Angel that allows the film to explore the violent dark side of this subculture. It has influenced all documentarians who’ve followed.

As critic Ewan Gleadow wrote last year on his blog Cult Following, “Death, skulls and all the vicious behavior associated with those moods are found not just within the film, but within the gang itself. Synonymous imagery is fast and cut well. By far the greatest draw Anger can offer is that of a faithful, chilling adaptation of the degeneracy and destruction.”

1960s Biker Movies

In 1966, Variety finally grappled with the phenomenon of low-budget, action-fueled biker films lighting up drive-ins across the country. A story in the January 26, 1966, edition of Daily Variety was a little dismissive about Roger Corman’s American International Pictures putting a new project, “Hell’s Angels on Wheels,” into production.

“’Hell’s Angels’ is, of course, the name taken by, and given to, the less-than-10% of motorcyclists who get 100% of the publicity,” Variety sniffed.

Released in 1967, “Wheels” turned into somewhat of a directorial showcase for Richard Rush, who went on to an Oscar nomination 14 years later for “The Stunt Man.” “Wheels” was also a key career building block for acclaimed cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs as well as an early credit for future superstar Jack Nicholson.

Variety

The year before, “The Wild Angels” became perhaps the most iconic of all the 1960s biker pics, boasting Peter Fonda, Nancy Sinatra and Bruce Dern in the leads as well as a screenplay with uncredited tinkering from Peter Bogdanovich. The box office success that Corman’s banner enjoyed signaled to Hollywood executives that two-wheeled tales could mean fast money.

“Hell’s Angels ’69” was perhaps a more déclassé example of the burgeoning biker film genre. The picture lacked the quality sheen of “Wheels” or the star power of “Wild Angels,” but it did boast appearances by several bona fide Hells Angels, including Barger, who even got a mention on the movie poster.

“Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” is neither from the ’60s nor is it a biker film, but this landmark 1971 indie hit from director Melvin Van Peebles borrowed the lean-and-mean action aesthetic of biker pics and utilized the Hells Angels in a key subplot.

‘Easy Rider’

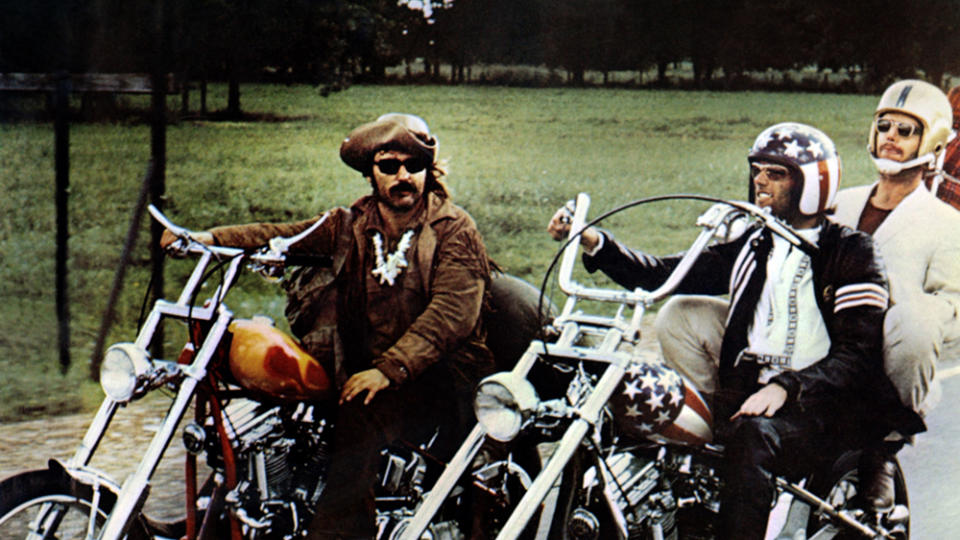

Simply one of the most influential films in cinema history, “Easy Rider” is the movie that gave us eternal “heavy metal thunder” along with the road trip of Wyatt (Peter Fonda) and Billy (Dennis Hopper) and lethal rednecks, LSD, free love, open highways, chopped bikes, fresh grass and a polarized America that might look familiar to anyone paying attention to today’s culture wars.

Everett Collection

Directed by Hopper, the conceit sprang directly from all the biker films that the actor-director had either been in or offered. It was Hopper’s vision, along with screenwriter Terry Southern, to take the rebel-seeking-freedom trope of the glut of previous biker films in a different direction by sprinkling in some peace, love and hippie-culture pretensions. By 1969, just two years after San Francisco reveled in the Summer of Love, the violent, psychotic, dangerously deranged outlaw bikers of Hunter S. Thompson’s “Hells Angels” book had become groovy dudes with fringy leather cowboy coats.

Altamont

The Hells Angels burnished their outlaw credentials forever with the 1970 documentary “Gimme Shelter,” which captured the chaos at the Rolling Stones’ December 1969 free concert at Altamont Speedway racetrack just south of Stockton, Calif. Footage of the crowd during the concert managed to capture a real-life fatal stabbing on film. The documentary helmed by brothers Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin was otensibly meant to be a record of a massive turnout for the Rolling Stones. But the concert famously became a deadly debacle.

Courtesy of 20th Century Fox

The movie has endured more as the obituary for the idealism and much of the foolishness of the Swinging ’60s. The film does not pull punches in examining what went wrong at the event, starting wit the decision to hire members of the Oakland chapter of the Hells Angels to provide security. Thanks to overcrowding, bad acid and the Angels’ misinterpretation of their duties, the event included the death of Meredith Hunter, an 18-year-old Black concert-goer who was reportedly seen carrying a gun and was savagely beaten by the Angels. The tragedy at Altamont was quickly twinned with the Manson Family murders as an eye-opening example of the countercultural violence beneath the era’s message of peace, love and understanding. And Altamont became the defining image of the Angels. The weight of that history may have been on Barger’s mind when he offered a bit of advice to readers in his 2005 book “Freedom: Credos from the Road.” “Live your life the Sonny Barger way? I don’t recommend it,” he wrote.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News