Srebrenica 25 years on: how the world lost its appetite to fight war crimes

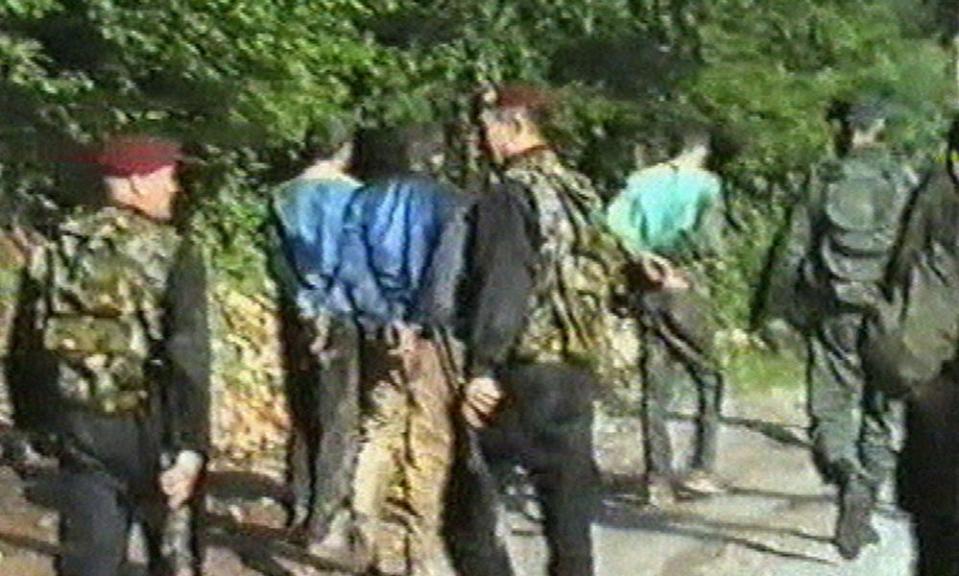

Ratko Mladić, the Bosnian Serb general convicted of ordering the execution of 8,000 men and boys from Srebrenica, will spend this week’s 25th anniversary of the slaughter in a cell in The Hague, where he has spent the past nine years.

A quarter century on from Srebrenica, the world has become painfully used to atrocities. Mass killings in Syria or Yemen no longer always make the news. China has incarcerated more than a million Muslim Uighurs and forced contraception, sterilisation and abortions on them.

When it comes to war crimes and crimes against humanity, Mladić now has plenty of company. What makes his case unusual today is the fact he was tracked down and made to face justice. Three years ago Mladić was convicted of genocide for the Srebrenica killings, in which men and teenage boys, captured when he led the 1995 attack on what was supposed to be a UN “safe area”, were gunned down in mass executions at sites scattered around north-eastern Bosnia.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) also found him guilty on five counts of crimes against humanity, and four war crimes counts for ethnic cleansing, the bombardment and sniping attacks on Sarajevo and holding UN peacekeepers hostage. The appeals chamber is now in a race with the 77-year-old convict’s fading health to complete the legal process while he is still alive.

Fourteen more Bosnian Serb officers and officials were convicted for their part in the Srebrenica massacre, including the Bosnian Serb separatist leader, Radovan Karadžić. In all, the ICTY passed sentence on 90 war crimes defendants.

The sister tribunal for Rwanda convicted and sentenced 93 people found responsible for the 1994 genocide there. The ICTY and ICTR were the first such ad hoc courts set up since the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, and reflected a widespread enthusiasm in the wake of the cold war for the world to do more in the face of mass atrocities. The post-Holocaust pledge of “never again” came back in currency.

Other UN-assisted special courts were established for mass crimes committed in Sierra Leone, in East Timor, as well as in Cambodia to bring some belated justice to the surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge.

The EU created a separate tribunal for Kosovo, which last month published charges against the president, Hashim Thaçi and others, for crimes committed when they led the Kosovo Liberation Army.

A special court set up in the Hague to investigate and pass judgement on the 2005 assassination of Lebanese prime minister, Rafik Hariri, in a bomb blast that killed 21 others, is expected to issue its most significant judgement imminently. In 2002, a permanent tribunal for atrocity crimes began operating in The Hague, the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Related: Trump targets ICC with sanctions after court opens war crimes investigation

“Those were exciting years. Those were what I call carpentry years for the war crimes tribunals,” said David Scheffer, who was US ambassador-at-large for war crimes issues from 1997 to 2001, and played a central role in the creation of several of the special courts. “We only had as a template Nuremberg and Tokyo, and we rebuilt those templates in the early 1990s, and we kept refining them through the 1990s.”

For Nerma Jelacic, a Bosnian refugee who became spokeswoman for the ICTY, it felt like a new era. “It was absolutely about that for me from day one,” Jelacic recalled. “What was important about it was that all that suffering and death was not for nothing, because lessons were going to be taken and applied in the future.”

The array of courts was created to bring mass murderers to justice. But the UN also made an effort to find ways to prevent genocide, to turn “never again” into policy. The principle of “responsibility to protect” was developed in the wake of the Bosnian and Rwandan genocides, and officially adopted in 2005. It stated that the international community had a duty to intervene if a state did not protect its own people.

I think it is a huge stain on our conscience what we have allowed to happen in Syria

Nerma Jelačić, ICTY

The principle was invoked in a 2011 UN security council resolution, which provided the legal basis for military intervention in Libya, principally to safeguard the population of Benghazi against Muammar Gaddafi’s forces. But the “responsibility to protect” principle was also fatally wounded on its maiden outing. The US, UK and France pressed on with their intervention until Gaddafi was toppled: Russia, which had abstained on the resolution, claimed it had been hoodwinked into acquiescing in regime change, and vowed never to be fooled again.

Gaddafi’s murder by a mob and Libya’s fragmentation marked the definitive end of an era for the global response to war crimes. Vladimir Putin returned to the presidency the year after the Libya intervention and steered Russia on an increasingly confrontational path against the west. The Arab Spring turned to a bloodbath in Syria, China under Xi Jinping became more repressive and more assertive on the world stage, and Donald Trump, who has disdain for multilateral institutions of all forms, won the US presidency in 2016.

It would be hard to imagine a more inhospitable climate for the “responsibility to protect” or for war crimes courts for Syria, Yemen or Myanmar.

“Everyone got cold feet after how the Libya intervention happened,” Jelacic said. “But it is a huge stain on our conscience what we have allowed to happen in Syria. Massacres and people being tortured to death has become normal for nearly 10 years.”

Meanwhile, the ICC, whose powers were limited at its creation by the major powers, has come under attack in recent weeks from the Trump administration, which has threatened court officials (and their families) with sanctions if they pursue investigations into US and allied actions in Afghanistan, or Israel’s operations in the West Bank and Gaza.

“It is so self-defeating. It undermines our credibility to pursue justice and rule of law, and the prevention of atrocity crimes overseas,” former ambassador Scheffer said. Against such a backdrop, the phrase “never again” rings especially hollow.

“Especially after the violence in Syria to me it sounds empty, spent, meaningless,” said Iva Vukušić, a historian at Utrecht University. When it comes to accountability for war crimes, however, Vukušić argued all is not lost. The prosecution of Mladić and others had left an indelible mark.

“Before the tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, one could reasonably expect after a civil war or a dictatorship that nothing happens. But now I think in the last 25 years we have really witnessed a change in expectations, with academics, researchers and activists demanding accountability. I think in that sense, we will not go back.”

Related: Head of ICC says US measures to curb court are unlawful

Trump’s assault on the ICC has prompted a backlash among its supporters, including America’s closest allies who have come out in support of the institution. A new prosecutor is currently being chosen, and a review of its operations is due by the end of the year, with the aim of rendering it more effective.

Meanwhile, in the absence of a special tribunal on Syria, courts in Germany, the Netherlands and Scandinavia have been investigating war crimes there under principles of universal jurisdiction. In April, a court in the German town of Koblenz began the trial of two former Syrian regime officials who had defected to Germany.

It is the first of many prosecutions, possibly hundreds, in the works. Evidence has been collected by the International Impartial and Independent Mechanism, set up in Geneva with the support of the overwhelming majority of the UN general assembly as a means of sidestepping the impasse of great powers in the security council to pursue justice in Syria.

The Koblenz trial also draws on some of the 800,000-plus Syrian regime documents smuggled out of the country over the years, often at considerable personal risk, by the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) an independent body supported in its work in Syria by the UK, Canada and Germany. It also collects evidence on Isis atrocities in Syria and Iraq.

Jelacic is now CIJA’s head of external relations. “The one thing that is salvageable is the notion of accountability – the notion of those responsible answering for those crimes,” she said.

“This is the straw to which I clutch now, which keeps me going, because you cannot undo the principles, the conventions, the international laws agreed by the state parties, and it is these laws that allow us to pursue justice such as we can for the Syrians. So that’s what cannot be undone.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News