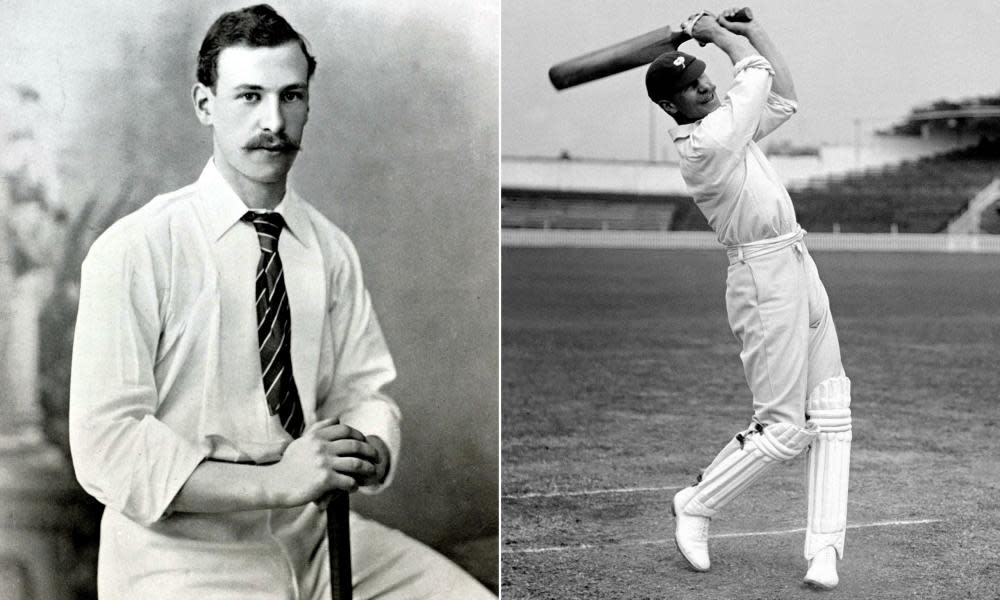

Stanley Jackson: a batting master, MP and sportsman who bewitched Cardus

This year marks the centenary of the debut in this newspaper’s sports pages of Neville Cardus, perhaps the greatest of all cricket writers. There has probably been enough written about the great man – may I refer you to Duncan Hamilton’s The Great Romantic, the winner of the 2019 William Hill sports book of the year award? – but reading his early articles throws up so many more fascinating questions than those simply about their author.

One obvious question was prompted by the first article published under his chosen byline, “Cricketer”, a summary of Lancashire’s prospects in the 1920 season.

The players had returned to training the previous day. “The weather was of a sort to humble the flesh, to stir up the rheumatics and the exposed nerves in the teeth,” Cardus wrote. “It was, in fact, a good day for another cup-tie. A spirit of intense keenness was in the air, which augurs well for the strenuous work to be done that summer.” Though of course there were few conclusions to be drawn from a session in the nets.

“The practice yesterday did not invite serious criticism,” he wrote. “The main job on hand was less the cultivation of style then the unloosening of the muscles after winter’s catalepsy. Still, a good cricketer is a good cricketer even at the first knock for the year, as far as technique goes. His mistakes will be due to stiffness and a slow eye, not to faulty style. The born cricketer, indeed, can go for years without touching a bat and yet reveal the hand of the master as soon as he picks one up again. Who does not remember that great innings of FS Jackson the first time he played the game after two or three years in South Africa?”

Related: Harsha Bhogle on lockdown, the IPL and the future of cricket

To which the answer, certainly 100 years on, is absolutely no one. Even in 1920 many readers must have scratched their heads; my search for further information suggested that if you happened to miss the next day’s papers you might never have known about it.

Stanley Jackson is known for a great many things – including playing the most home Tests without appearing away (20), winning every toss as England’s captain in the 1905 Ashes series (he also topped the averages for batting and bowling), and the over bowled for Yorkshire against the Australians in 1902, in which four wickets fell and he finished with figures of five for 12 (George Hirst took the other five wickets for nine runs; the ball was cut in half and shared between them).

He spent 11 years as a Conservative MP and five as governor of Bengal, and fought in the Boer war and in the first world war, as the commander of a battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment. Born in Yorkshire he was educated at Harrow, where the practice of fagging – which forced younger boys to act personal servants of the oldest – was still very much in favour. Jackson’s fag was Winston Churchill.

Jackson also survived an unlikely number of near-death scrapes, including an attempted assassination by sword (his evasive manoeuvre, he said, was “the quickest duck I ever made”), an attempted assassination by gunfire (she missed), a direct hit on his house during the blitz (“the floor at the far end of the room seemed to rise and come straight at us”) and being run over by a taxi (“I don’t think there is really much the matter, but it gave me a bit of a jolt at my age”).

He was also known for his sportsmanship, once pulling off his gloves after being dismissed to applaud a particularly fine catch. “What we have to do,” he said of cricketers during the Bodyline series, “is to be quite certain in playing the game that we do not do anything on the field which can be regarded as approaching even the borderline of the undesirable.”

So there was no lack of material for his obituarists when he died in 1947, at the age of 76, and there was absolutely no mention of the innings Cardus found so memorable. Even at the time it hardly made much of an impact. “Jackson brightened the proceedings by a remarkable display of batting … He allowed few opportunities of scoring to escape him, strong driving being the main feature of his cricket,” was the sum of the Guardian’s reporting of it.

There was certainly nothing else worth remembering about the game it came in, a three-day match between Essex and Yorkshire at Leyton. The first two days were rained off, making a draw a near-certainty when play started. Essex were bowled out for 89 and Yorkshire’s reply started badly when John Tunnicliffe was dismissed for a duck. At this point, out came Jackson.

Jackson had last played for his county in 1899, before he first travelled to South Africa to fight in the second Boer war. He played one match on an injury-enforced trip home in 1900, for Gentlemen against Players at the Scarborough Festival, when in his first innings he scored 134. “Some little pressure had to be brought to induce him to play at all, but yesterday at all events there were few remaining traces of weakness or ill-health about him,” wrote the Guardian. “Indeed, he has seldom been seen to play better.” Then he returned to the front, not to be seen until May 1902.

“And now, having once more appeared in first class cricket, he begins in wonderful style by putting together another three-figure score,” wrote Sporting Life. “This is indeed a fine record, and it says much for his great natural abilities as a cricketer that he should be able to jump at once into form. In a dull and otherwise uninteresting afternoon’s cricket on Saturday Jackson’s batting was the one bright spot. At the outset he was obviously ill at ease, and on the slow wicket failed to time the ball properly, but once he had mastered the peculiarities of the pitch he batted delightfully, his defence being as strong and safe as his driving was powerful.”

At stumps he had scored an unbeaten 101, which proved he was precisely as good at returning to first-class cricket as he was at departing from it – nearly three years earlier, his last innings for Yorkshire had ended on precisely the same score.

• This is an extract from the Guardian’s weekly cricket email, The Spin. To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News