Stargazing in March: Strange-shaped stars in the Spring sky

Sculpted by the gravity of black hole, Cygnus X-1 is shaped like a cosmic pear

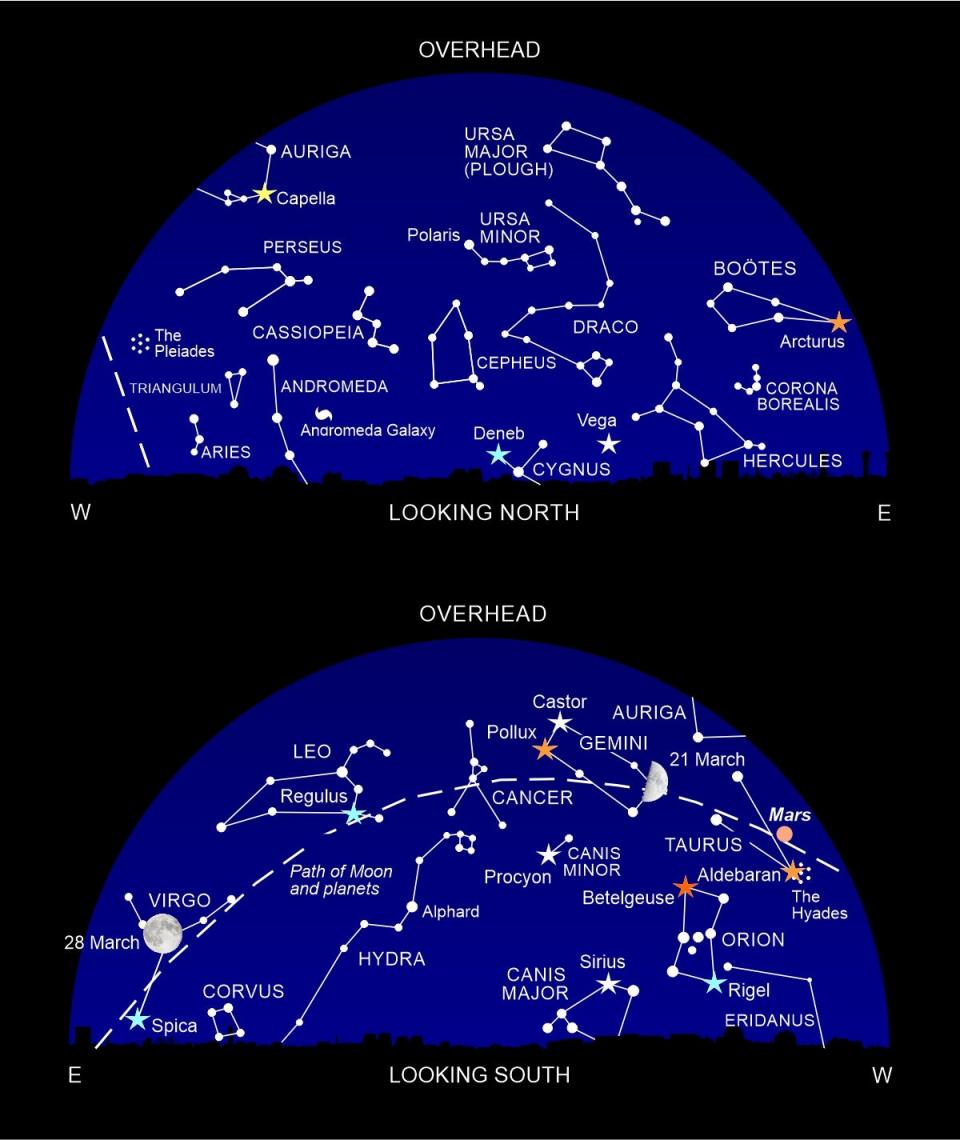

(Nasa)Spring is on the way, and there are signs in the sky. The brilliant star patterns that have been on view all winter – Orion, the hunter, and his entourage – are sinking down to the west, their place taken by Leo (the Lion) and Virgo (the Virgin). Both these constellations boast a brilliant blue-white star as their principal feature, and each of these is weirdly shaped.

The lion’s heart is marked by Regulus, a name meaning “little king”. Though the name is Latin, it doesn’t date from the time of the ancient Romans (who didn’t have much interest in astronomy). Instead, it was named by the Renaissance astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, best known for insisting the planets orbit around the Sun, rather than the Earth.

Regulus is almost four times heavier than the Sun and burns much more fiercely. Its powerful nuclear reactions make it shine 300 times more brilliantly than our local star, with its surface temperature of 12,000C giving Regulus a blue-white glare.

What’s most odd about Regulus is its shape. If we could see this star up close, it wouldn’t be a spherical ball like the Sun, but a flattened tangerine shape. Its polar regions would appear much brighter than the distended equator because they lie closer to the star’s energy-generating core.

It’s all down to the fact that Regulus is spinning incredibly rapidly. While the Sun rotates once in a leisurely 27 days, Regulus whips around in just 16 hours. The rapid rotation rate flings its equatorial regions outwards and flattens the star. If Regulus spun just 5 per cent faster, rotational forces would rip the star apart.

Spica – the jewel in the crown of Virgo – is also blue-white in colour, showing it is also an incredible hot object. But there the resemblance with Regulus ends. Zoomed in, we’d see that Spica consists of two stars so close that they almost touch one another, and orbiting each other in just four days.

These stars are near siblings, seven and 11 times heavier than the Sun, with temperatures over 20,000C. They are so near that the gravity of each star distorts the other, stretching them out towards each other. Viewed up close, Spica would look like two giant luminous eggs, orbiting each other point-to-point.

Even Spica doesn’t represent the extreme shapes that stars can take. Take, for example, Cygnus X-1, a distant star that’s unlucky enough to be orbiting a black hole. The black hole’s powerful gravity is stretching out the massive blue-white star, and ripping gas from the elongated end in a stream of gas that heads towards the black hole. Close up, we would see a star that resembles a cosmic pear, its stalk channelling gas down to the black hole where it disappears from our universe.

What’s Up

Over in the west this month, a pair of red eyes is glaring in the evening sky. One is Mars, much in the news at the moment following the arrival of an international flotilla of spacecraft at the Red Planet. The other is Aldebaran, the angry bloodshot eye of Taurus (the Bull), facing his adversary, the great hunter Orion.

There’s a lovely sight on 19 March, when the crescent Moon lies between Aldebaran and Mars, with the sparkling Seven Sisters – the Pleiades star cluster – to the right.

The familiar seven stars of the Plough are almost overhead. They’re the brightest members of a larger pattern, Ursa Major (the Great Bear), with the quadrangle of four stars marking her body and the three stars to the left of her tail. Between the celestial bear and the southern horizon, you’ll find the distinctive shape of Leo, a crouching lion. To the left, the stars of Virgo (the Virgin) form a giant Y-shape in the sky.

There’s more planetary action in the morning sky, with the solar system’s two largest worlds rising in the southeast around 5am. To the right is Saturn, well separated from brilliant Jupiter. At the start of the month, you’ll find Mercury very close to Jupiter, but it quickly sinks into the dawn twilight.

Diary

5 March (am): Mercury very close to Jupiter

6 March, 1.30am: Last quarter moon; Mercury at greatest elongation west

13 March, 10.21am: new moon

18 March: Moon near the Pleiades

19 March: Moon near Mars

20 March, 9.37am: Spring equinox

21 March, 2.40pm: First quarter moon

23 March: Moon near Castor and Pollux

25 March: Moon near Regulus

28 March, 1am: British Summer Time begins

28 March, 7.48pm: Full moon

Philip’s 2021 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year.

Read More

Stargazing in January: Brilliant stars and astronomical goodies

Yahoo News

Yahoo News